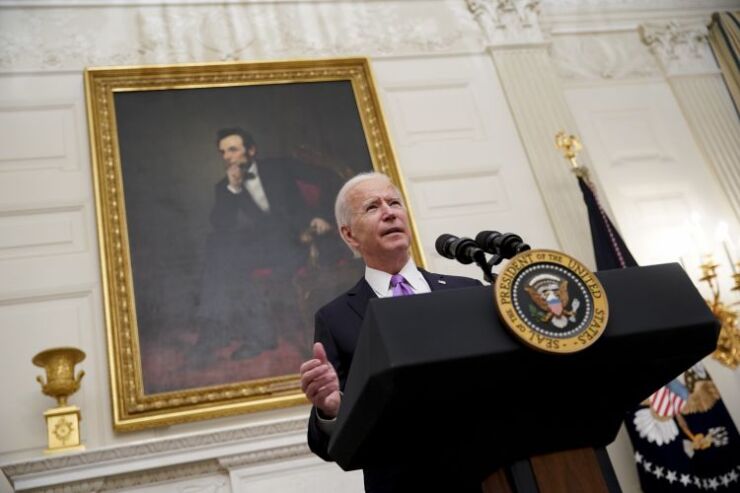

President Biden wants banks to make customer data portable. The directive can be interpreted in many different ways and may prove easier said than done.

The White House, as part of a broad executive order meant to promote competition across the U.S. economy, says it “encourages the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau to issue rules allowing customers to download their banking data and take it with them.” The administration wants to “make it easier and cheaper” for consumers to take their business to rivals.

How much of an effort this will require banks to make from a technology and business point of view will depend on the rules the CFPB writes. The agency could validate the current state of consumer data sharing in the U.S., in which aggregators pull data out of banks and give it to fintechs on behalf of consumers. Or it could require something new — actually letting consumers download their own data in a usable format onto a device or into an online storage account, or allowing customers to have their data sent from one bank to another.

The presidential order, issued Friday, specifically urges the CFPB to “consider commencing or continuing a rulemaking under section 1033 of the Dodd-Frank Act to facilitate the portability of consumer financial transaction data so consumers can more easily switch financial institutions and use new, innovative financial products.”

In doing so, the order is adding weight to 1033 itself, which asks the CFPB to create rules governing consumer financial data access and sharing. In October, the bureau

A spokeswoman for the CFPB declined a request for comment, but pointed out that the bureau is in the active prerulemaking stage for Dodd Frank 1033 and that its “next completed action under 1033 will be in April 2022.”

Today, for the most part Americans have the second thing the executive order seeks: access to new, innovative financial products. Most anyone can sign up for a fintech like Robinhood or Petal and have relevant bank account data sent to the fintech by a data aggregator like Plaid, Finicity, MX or Envestnet Yodlee. Sometimes the aggregators use an application programming interface, but more often they use screen scraping to obtain consumers’ online banking username and password and then copy account data that gets sent to the fintech. Sometimes this method fails, either because the bank blocks the screen scraping or this activity causes a bottleneck or triggers a security mechanism.

But the order’s first demand — that consumer banking data be portable so that consumers can easily download their own data or have their existing bank send their data to a new bank or fintech — does not exist in the U.S. today. Banks don’t offer this, most Americans wouldn’t think to ask for it, and if someone did think to ask for it it’s doubtful that the existing bank would comply. Those realities stem from the fact that there’s no rule requiring portability yet and from the technical challenges involved.

“Being able to tell one bank you're opening an account with another bank and then everything sort of switches over including payments and things of that nature, we haven't really seen that functionality here,” said Matthew Homer, executive in residence at Nyca Partners in New York.

How it’s done in Europe

Data portability is one of the tenets of the European Union’s General Data Protection Rule, which took effect in May 2018. “The data subject shall have the right to receive the personal data concerning him or her, which he or she has provided to a controller, in a structured, commonly used and machine-readable format and have the right to transmit those data to another controller without hindrance from the controller to which the personal data have been provided,” the rule states.

European Banking Federation guidelines state “data portability is a right to receive personal data processed by a data controller, and to store it for further personal use on a private device, without transmitting it to another data controller.”

In the U.K., banks are required to use a common, open-source API to send that data to other financial services providers at the customer’s request. Because of the common API, data can be freely shared among banks without the need for aggregators. In the rest of Europe, there is not a common API requirement, and data aggregators play a bigger role.

The U.K. didn’t provide for the part of GDPR that requires banks to make data available to download onto another device. That wasn't considered important to improve financial competition.

“Our intention was to remove the advantage that banks have through their unparalleled access to their customers’ transaction histories and support the entry of new banking service providers who aren’t necessarily banks," said Bill Roberts, head of open banking at the Competition and Markets Authority in London. "That’s now starting to happen.”

The U.K.'s open banking rules also require that when someone closes their bank account they must be provided with an electronic copy of their transaction history.

Some think the U.S. will adopt the U.K. version of data portability.

“The Biden executive order appears to call for an approach similar to the U.K. Open Banking initiative,” said Peter Swire, associate director for policy at Georgia Tech's institute for information security and privacy. “That initiative has been generally successful, although it took an active effort by U.K. agencies to overcome inertia and put portability into practice.”

Swire noted that strong authentication and security are needed for this to work, “so that impostors cannot transfer funds or personal information.”

Aggregators focus on access, not portability

A possible role model for U.S. banks is Google. Its Takeout service lets users view all the services for which Google stores their data, choose the data sets they want to download, and determine a file type and destination for that data, such as Google Drive or Dropbox.

A Google Takeout-style portability is unlikely to be mandated by the CFPB rules, according to John Pitts, head of policy at Plaid, a San Francisco-based data aggregator.

“I think you will continue to see an evolution of services like Plaid building interoperable portability infrastructure,” Pitts said. “That's more the direction of what you’re going to see as opposed to a mandated Google Takeout or GDPR-style intervention in the market.”

That’s because the CFPB is charged with creating rules around Dodd Frank 1033, which is about data access, not data portability, he said.

“When you look at 1033, it’s about consumers having the right to access their financial information,” Pitts said. “It’s hard to read a mandate for full portability from one financial institution to another into the statutory language of 1033.”

The rules are likely to make switching banks easier, Pitts said, but only where the receiving banks invest in APIs and data aggregator services to make that possible. So if Bank of America has an API and a relationship with Plaid, it could ask new customers if they want to use Plaid to import all of their bank account history from their existing bank to Bank of America.

U.S. data aggregators say there’s no need to give consumers direct access to their own data.

The data aggregators have built large businesses around taking data from banks and giving it to fintechs. If their take on the executive order prevails, it will be a windfall for them: All banks will be forced to work with, and pay fees to, the data aggregators. If the order is interpreted as letting consumers serve themselves, or even letting banks freely exchange data with each other, the aggregators’ business models could be challenged or limited.

According to Jane Barratt, chief advocacy officer of MX, which is based in Lehi, Utah, data portability simply means the sending of customer data from banks to fintechs through APIs the way companies like MX already do.

“We're actually doing it for the majority of the customers on our platform today,” she said. “Where it gets a little trickier is the long tail,” meaning smaller banks that haven’t written data-sharing APIs.

“It is going to potentially be years before the entire industry, including the smallest community banks, are able to participate equally,” she said. “The pieces that aren't necessarily acknowledged are things like liability, what happens in case of a breach, and how do we keep a level playing field so that if you choose to bank at a tiny community bank or a megabank, you won’t be at a disadvantage in terms of data availability and portability.”

The important thing is for consumers to be able to sign up for budgeting tools and other services and have their bank account data populated in those apps, according to Chad Wiechers, senior vice president of data acquisition and strategy at Envestnet Yodlee.

At the Financial Data and Technology Association, a trade group for data aggregators and fintechs, Executive Director Steve Boms says the way things work in the U.S. today is OK, except he would like more banks to share all their customer data with aggregators through APIs.

“If you're lucky enough to have an account with a financial institution that is more forward-thinking on this score than some others, then you might encounter no problem taking your data from that bank and utilizing it with a third party,” Boms said. “But for many others, you don't have that right. There are difficulties and restrictions and hurdles that you encounter.”

By forward-thinking institutions, Boms means banks that are working with data aggregators and that don’t restrict how much data the aggregators can take.

The work ahead for the CFPB

One thing is certain: the executive order gives the CFPB a push to finish writing the data-sharing rules it’s been working on for several months.

“It's clearly going to be a journey,” said Nyca's Homer, who previously was executive deputy superintendent of the research and innovation division at the New York State Department of Financial Services. “If you look at the experience in the U.K., it has taken quite a while and there will be standards to work out. The allocation of liability and things of that nature will have to be worked out. But the really important first step is to make it very clear that consumers have rights related to that data and to clearly articulate those rights. A lot of work will have to be done to ensure that the plumbing and the practices and everything that exists behind that work in the best interest of the consumers.”

This idea that consumers should have control over their own data is something banks, fintechs and data aggregators all say they want.

“That, to me, means being able to access that data however you want, whether it's logging in to a bank yourself and downloading to an Excel spreadsheet or using a third-party solution that you as a consumer trust and have chosen to provide that functionality to you, and whenever you want,” Homer said.

And when consumers have granted permission for some use of their data, they should be able to see where their data is going and be able to throttle or turn off access to their data, he said.

“I think we need to get to a place where consumers can exercise more agency in terms of exactly what data elements they want to make available for portability,” Homer said.