It has been over three months since the Federal Reserve Board created a lending facility for investment banks, and so far the central bank's action has been all quid, no pro quo.

Eventually, lawmakers and regulators will get around to mitigating the moral hazard that the Fed created when it extended credit to investment banks — relying upon narrow authority that confers few, if any, of the enforcement and examination powers necessary for prudential regulation. If a prudential regulatory regime is the price of access, as has been widely suggested, it will have to be levied by Congress, which is unlikely to do so in an election year.

By the time the topic gets an airing next year, the country will have a new president and a new balance of power on Capitol Hill. The issue will be thrown into a legislative mix that is likely to include a broad response to the credit crisis, and it will involve a regulatory restructuring that has not received a serious hearing in over a decade.

The debate will extend beyond commercial banks and investment banks to other entities that could pose systemic risk, including insurance companies, hedge funds, and private-equity funds. About the only certainty is that restructuring will be lobbied to within an inch of its life, and perhaps further. Yet some legislation seems likely.

"What pushes this forward is the searing experience" of the past year, said Alan Blinder, a former Fed vice chairman and now a professor at Princeton University. "That will not have been forgotten when a new administration takes office in January 2009. In fact, it may still be going."

The big questions: Will the regulatory umbrella be extended, and to whom? What additional rules, supervision, and examinations will apply to these entities?

The question of greatest interest to the regulators, whose very existence depends upon protecting and expanding turf, is who would do these things.

As that debate coalesces, market observers are looking for more information on the Fed's informal supervision of investment banks. The program, which began in March when it established the primary dealer credit facility, comes down to four firms whose failure would raise systemic-risk issues: Merrill Lynch & Co. Inc., Goldman Sachs Group Inc., Lehman Brothers, and Morgan Stanley. Most of the other primary dealers are affiliated with banking companies that already have access to the discount window.

The Securities and Exchange Commission, the primary regulator for these companies, is esteemed for its enforcement powers that provide some market discipline, but it has little experience with prudential supervision. In testimony before the Senate last week, Erik Sirri, the SEC's director of trading and markets, said it was working on a memorandum of understanding with the Fed laying out their interim, enhanced scrutiny of investment banks.

The Fed would not discuss the details of its joint supervision with the SEC. A spokesman for the SEC would not comment beyond Mr. Sirri's Senate testimony on June 19, in which he said the memorandum would provide "a framework for bridging the period of time until Congress can address through legislation fundamental questions about the future of investment bank supervision, including which agency should have supervisory responsibility."

Of course, the longer the agencies delay spelling out the additional steps they are taking during this interim period, the more discretion they have. Once they disclose the terms, they will be held accountable for what they do — and do not do.

The Fed's unhurried pace in this regard is ironic, given the powers it cited in creating the facility. The opening words of Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act are "In unusual and exigent circumstances." To date the central bank has displayed little of that exigency in explaining precisely what it is doing.

The statutory language also implies that the facility must eventually close — at some point, circumstances that persist cease to be unusual. The facility is set to close in September, but the Fed could keep it open at its discretion.

And merely closing the window would not solve the problem, because market participants assume the Fed would reopen it if circumstances again became "unusual and exigent."

It is "almost impossible to go back," in the words of Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. Chairman Sheila Bair.

Jonathan Macey, a professor at Yale Law School who teaches bank regulation, said the Fed should clarify its intentions.

"When they say it's temporary, there are no guidelines or criteria for identifying circumstances for when access will be closed and when it might open again," he said. "People complain about investment banks being opaque. Nothing is more opaque than the way the Fed has been regulating."

For now the Fed's beefed-up presence at the investment banks involves bank examiners but not examinations. Vice Chairman Donald Kohn said in Senate testimony last week that the central bank's role was "specifically to assess the adequacy of liquidity and capital" and did not encompass risk management.

Ernest Patrikis, a former general counsel of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York who is now a partner at Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP, said: "The Fed is going into those primary dealers as a creditor doing due diligence. It is not an examination, there is no cease-and-desist authority. There is no regulatory authority."

Right now "it's just 'You're my debtor, and if I don't like what you're doing, I'm not going to lend to you,' " Mr. Patrikis said. "That can go forward for some time."

But that cannot go forward forever, and keeping the window open certainly will become increasingly uncomfortable for the Fed.

A second element of the powers it relied upon to open the facility requires it to "obtain evidence" that any entity getting credit is "unable to secure adequate credit accommodations from other banking institutions."

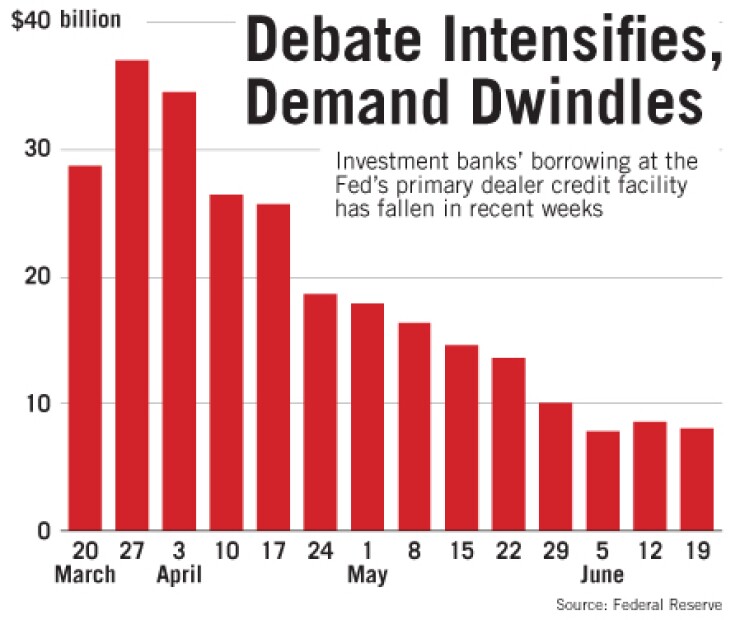

There is little evidence that the retching dislocations of March persisted through June. Investment banks took $37 billion from the window the first full week it opened, but in each of the past three weeks they have borrowed less than $10 billion.

In a speech last week, Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson said the central bank's increased responsibility as a market stabilizer would require powers beyond additional information-gathering.

"We must also define the scope of the Fed's role in identifying and constraining risk-taking that can detrimentally affect the financial system," he said. "This likely requires authority to intervene to prevent the buildup of conditions that create significant risk to the stability of the financial system."

He did not clarify what form that intervention might take, but when policymakers start talking about parity between commercial and investment banks, the big issue is capital.

"Inducing institutions to hold stronger cushions of capital and liquidity in periods of calm may be the best way to reduce the amplitude of financial shocks on the way up and to contain the damage on the way down," New York Fed President Timothy Geithner said in a June 9 speech.

The obvious consequence of banklike capital requirements is less leverage, which is no small issue for an industry dependent on leverage to generate huge profits in more sanguine markets.

"This is a serious matter because if you are scaling leverage from 25 to 1 to 12.5 to 1, the same amount of capital will support only half the assets and presumably bring in half as much revenue," Prof. Blinder said. "You are talking about something that goes right to the profitability of this industry."

Douglas Landy, a banking partner with Allen & Overy LLP, said the leverage issue is a complicated one to legislate and is made more so by global competitiveness issues — European banks are not subject to a leverage ratio.

Another complicated issue: the limits on products and activities.

The restriction on activities is "one of the fundamental risk-reduction tools in banking law," Mr. Landy said. "Both the banks and the bank holding companies are limited in what they can do, and that wipes out large areas of riskier activities that are available to investment banks, such as real estate development."

In an op-ed published last week in The Wall Street Journal, SEC Chairman Christopher Cox acknowledged a "lack of symmetry" between the treatment of investment banks and commercial banks, but he cautioned against imposing similar regulation.

"For financial institutions whose lifeblood is trading, not lending, there is as yet no agreed-upon 'apples to apples' comparison of balance sheets and leverage metrics," he wrote. "We must be careful to construct a regulatory approach that meets our regulatory objectives without discouraging risk-taking or neutering Wall Street's ability to fuel economic growth and innovation."

Ms. Bair has been less bashful on the topic. In a speech last week she reiterated her call for "greater parity" between investment and commercial banks, including a regulatory regime with most of the same supervisory bells and whistles.

She also suggested that investment banks presenting systemic risk be subject to a resolution process similar to the one used for banks — a proposal Mr. Paulson signaled in his speech that he would be willing to consider.

A common observation is that the functions of the country's largest banks and its large investment banks have grown inexorably closer in the past two decades. There is no shortage of market observers claiming it is time for the regulatory regime to catch up to the market's evolution. To them, creating the dealer facility without additional regulation is an obvious inconsistency.

"If brokerages and investment banks are to have access to a discount window-type of facility, then they need to be brought under safety-and-soundness regulation analogous to, but not precisely identical to, that of banks," Prof. Blinder said.

Joseph Mason, a professor at Louisiana State University's Ourso School of Business, said the investment banks should be regulated "on the basis of the large-bank supervisory model: on-site examiners, intimate access to the books and records."

Investment banks, of course, would just as soon have this interim period of access without consequence extended in perpetuity.

Travis Larson, a spokesman for the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, said the trade group for the large investment banks is exploring the issue and intends to put out a paper this summer on regulatory restructuring. He would not comment further in advance of its release.

Prof. Mason argued that the new regulatory setup should cover all the large investment banks - even those that would gladly give up discount-window access if it meant more regulation.

"You've got to have everyone in, or the system will fail," he said. "Merely allowing the weak to borrow with no cost to the system as a whole, and not full participation from the strong as well as the weak, puts you in a very obvious moral hazard position that will use up the resources behind the window very quickly."

Prof. Macey noted that the Bear Stearns Co. rescue stretched the federal safety net beyond insured bank deposits.

"They are creating a really bizarre, unfair regulatory landscape between commercial banks and investment banks," he said. "There is no ceiling on the protection for the investment banks. The Fed bailed out the entire liability side of the balance sheet at Bear Stearns."