If Fannie Mae's third-quarter report will be most remembered for a massive, if well-telegraphed, $29 billion net loss, also noteworthy was new data showing a huge spike in its acceptance of unsecured bridge loans designed to help delinquent homeowners avoid foreclosure.

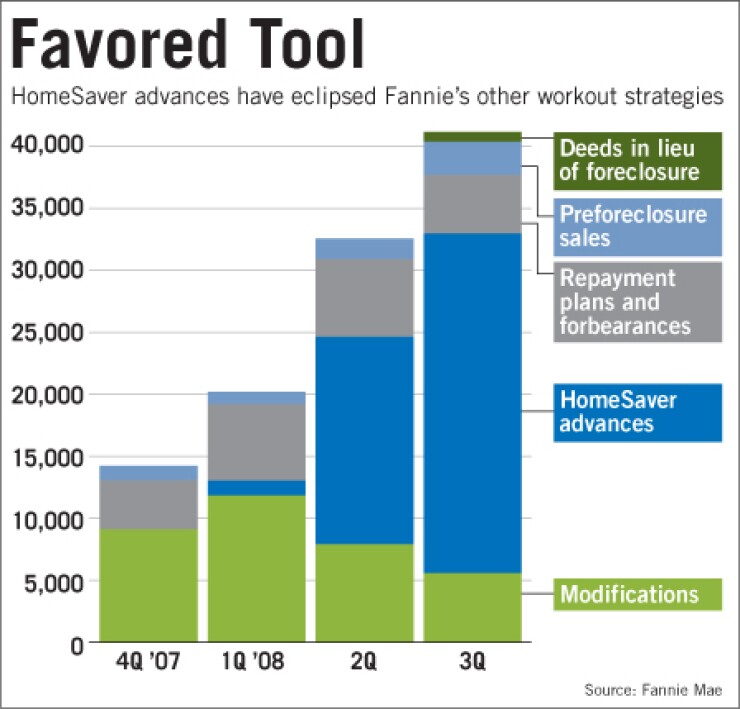

The HomeSaver Advance program — in which a servicer makes a personal loan to the homeowner (the average loan to date is around $6,700), sells it to Fannie, and brings the mortgage current — made up by far the biggest portion of the government-sponsored enterprise's workouts last quarter. The advances dwarfed all other workout types, including modifications of mortgage terms.

The extension of so much short-term credit offered another reminder that financial services policy and practice in the third quarter was very much about finding stopgaps. What comes next remains an open question.

"The concern would be that, if you use this for everybody, then you might just be kicking the problem down the road," said Terry Couto, a partner at Newbold Advisors LLC.

Fannie would not make executives available to discuss the issue Monday.

Through its servicers, the GSE provided about 27,000 unsecured advances last quarter, up from roughly 16,000 in the second quarter, according to a slide presentation Fannie posted on its Web site Monday. All told, the GSE had bought 45,000 such loans as of Sept. 30, according to its third-quarter report filed Monday to the Securities and Exchange Commission.

By contrast, Fannie modified slightly more than 5,000 mortgages in the third quarter, down from more than 10,000 in the first quarter, according to the slide presentation.

Fred Cannon, the chief equity strategist at KBW Inc.'s Keefe, Bruyette & Woods Inc., questioned the wisdom of offering up to $15,000 in unsecured loans when the recidivism rate for loan modifications is 50% and, in his view, probably higher for HomeSaver Advance borrowers. "This is a quick fix," he said. "It's essentially a bridge loan to borrowers until they can do a modification."

Mr. Cannon said he was surprised that Fannie modified far fewer loans in the third quarter than it had in any of the preceding three quarters; he suggested that, with home prices falling, modifications are becoming more difficult. "It's hard to modify a loan that is underwater and in which the borrower is behind on payments," he said.

Bruce Marks, the president of Neighborhood Assistance Corp. of America, which advocates loan modifications, said: "Taking the loans out of being delinquent and making them current without changing the underlying unaffordability of the mortgage" paints "a deceptive picture of overall loan performance."

When HomeSaver Advance was unveiled in February, it was touted as a way for Fannie to avoid buying loans out of mortgage-backed securities pools and for servicers to cure a loan immediately and move on to the next borrower.

Mr. Couto said HomeSaver Advance could be considered "a brilliant accounting move" because it brings a lot of borrowers current and relieves Fannie of the need to reserve for losses on loans repurchased out of pools.

However, Fannie does book a loss for the difference between the face value of the advances and market value. For example, advances it bought through Sept. 30 totaled $301 million but have a carrying value of $7 million.

"The fair value of these loans is substantially less than the outstanding unpaid principal balance for several reasons, including the lack of underlying collateral … the large discount that market participants have placed on mortgage-related financial assets, and the uncertainty about how these loans will perform," Fannie said in its filing.

Still, Fannie's $519 million of combined third-quarter losses on HomeSaver Advance loans and mortgages repurchased from securitizations was about 23% less than its repurchase-related losses a year earlier.

The GSE's third-quarter net loss was largely driven by a $21.4 billion charge against its deferred-tax assets. It said the charge reflected a determination that "it was more likely than not that the company would not generate taxable income in future periods sufficient to realize the full value of these assets."

The charge left Fannie with $4.6 billion of deferred tax assets. Fannie had disclosed about two weeks ago that it was likely to wipe out most of its deferred-tax assets.

Fannie's net worth fell to $9.3 billion at the end of September, from $44 billion at Dec. 31. The Treasury Department has pledged to inject up to $100 billion into Fannie (and the same amount into Freddie Mac) to make up for any negative net worth. The government seized the two GSEs Sept. 6.