The June 2025 proposal by U.S. bank regulators

The proposed changes would harmonize holding company and bank-level standards, reduce regulatory capital friction on Treasury market intermediation and better support monetary policy transmission. It rightly rejects unjustifiable asset-based exclusions and instead recalibrates thresholds to preserve the leverage ratio as a broad, risk-agnostic floor. Those criticizing the proposal for the threshold reduction should place more faith in the risk-based capital standards that adequately address their concerns. The proposal would result in a mere 1.4% reduction in aggregate GSIB capital requirements — not enough to ignite systemic instability, but enough to matter for bank-led market liquidity.

But regulators should not view this as the finish line. The underlying fragility exposed in 2023 — namely, the false comfort provided by capital ratios inflated by underwater securities — remains unaddressed. This risk should be addressed not just in the eSLR but also in the calculation of the Tier 1 leverage ratio. For all but the GSIBs, the existing treatment of accumulated other comprehensive income, or AOCI, reversals in capital rules pretends that losses on available-for-sale, or AFS, securities don't matter unless realized. But when liquidity dries up, and these securities need to be sold, the fiction is exposed. This dynamic contributed directly to the unraveling of Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic. Capital looked strong — until it wasn't.

Current capital treatment for all banks suffers "held-to-maturity," or HTM, dilution. Any bank can attest to the FASB-required "intent and ability" to hold an asset to maturity that has the potential to extend beyond the next business cycle, like mortgage-backed securities with underlying coupons as low as 2% that have current weighted average lives exceeding a decade. In fact, false confidence in "ability" is an excellent risk accelerant. Bank of America, for instance, right around the time that a "systemic risk designation" was called by U.S. bank regulators, had unrealized losses on mostly long-dated HTM securities amounting to nearly 70% of its common equity Tier 1 capital. Had the risk revealed from the 2013 failures actually been a systemic one, how should we have judged Bank of America's readiness?

Large banks, like the one where I chair the risk committee, are subject to comprehensive capital analysis and review stress tests. At times, it's hard to imagine a world where these high-stress scenarios would actually play out in reality. Yet, we've recently viewed a scenario for which Bank of America's actual capital strength would have proven profoundly wanting. Leverage ratios are where we should be accounting for this risk.

Senate Banking Committee ranking member Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., sent a letter to banking regulators urging them to preserve the enhanced Supplemental Leverage Ratio, warning that a rollback would only enrich bank shareholders.

Leverage requirements, unlike risk-weighted ones, are meant to constrain gross exposure irrespective of asset class. That's their virtue. But counting unrealized losses as equity undermines that purpose. It hides interest rate and liquidity risk and delays corrective action.

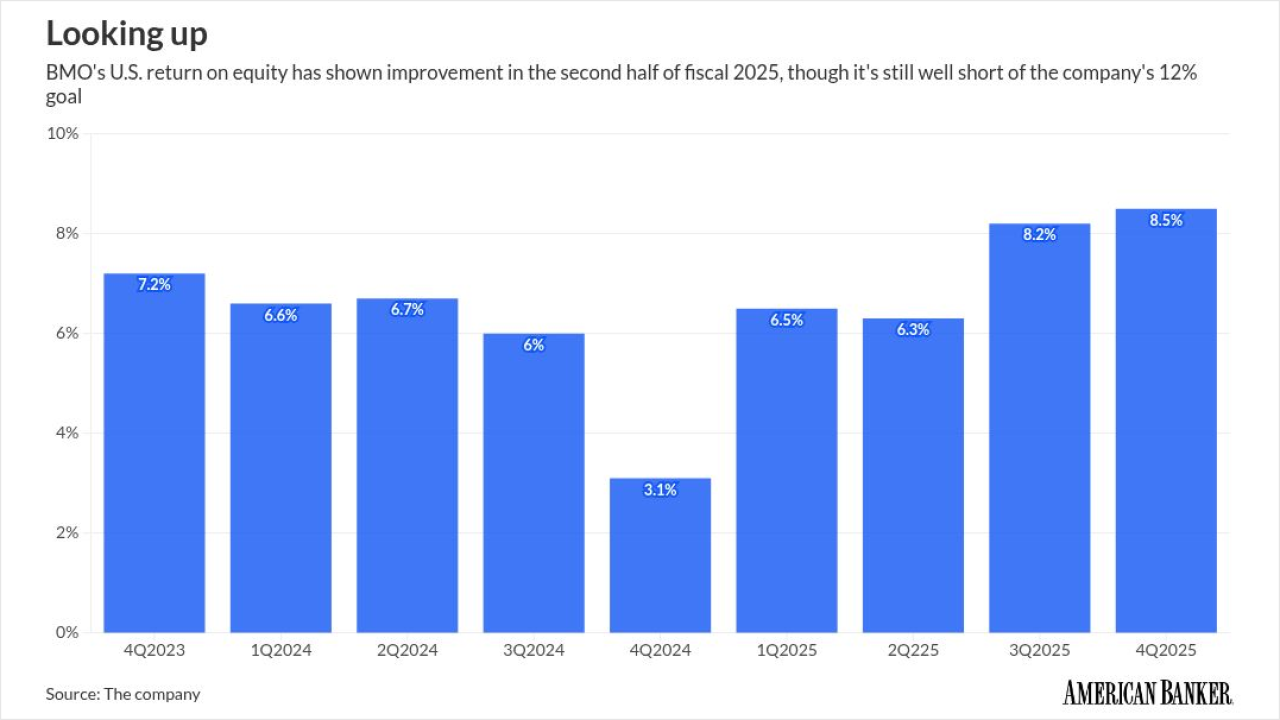

When rates began rising in 2022, banks had the liquidity and optionality to reposition. They didn't, because the regulatory capital treatment of these unrealized losses gave them no reason to. Had unrealized losses flowed through capital for leverage purposes, they would have responded early — before duration traps metastasized into solvency threats. Moreover, like uncleared landmines following a ceasefire, these capital-trapped securities remain on many banks' balance sheets silently overstating resiliency. This is so because nearly half the banks in the U.S. today continue to suffer significantly lower returns on equity due to negative carry on low-yielding securities; they need to borrow significant high-cost funds from the likes of the Federal Home Loan banks to avoid crystalizing the accumulated securities losses that would decimate their regulatory capital now that the post-COVID liquidity surge has left the banking system.

As a result, the overall risk profile of banks is worse than it should be, as we head into what may potentially prove a lengthy and far-reaching commercial real estate adjustment. Banks will be far less able to weather this storm because their balance sheets are weaker than they appear to be based on regulatory capital measures.

If regulators want to preserve the risk-based framework's focus on credit, they can keep reversing unrealized losses for risk-weighted ratios. But leverage ratios are the right tool to catch excessive risk accumulation in banks' securities books, including interest rate and liquidity mismatches. Fix that, and you can safely calibrate the leverage-based ratios lower, as this proposal does. Ignore it, and you simply reload the systemic gun for the next crisis.

The June 2025 proposal improves the U.S. capital framework by making leverage a true backstop, not a choke point. But a backstop is only as good as what it measures. Unrealized losses are real. The only question is whether we act before or after they trigger fire sales and depositor runs. This moment offers a rare chance to align capital standards not only with Basel norms, but with economic reality. Regulators should take it.