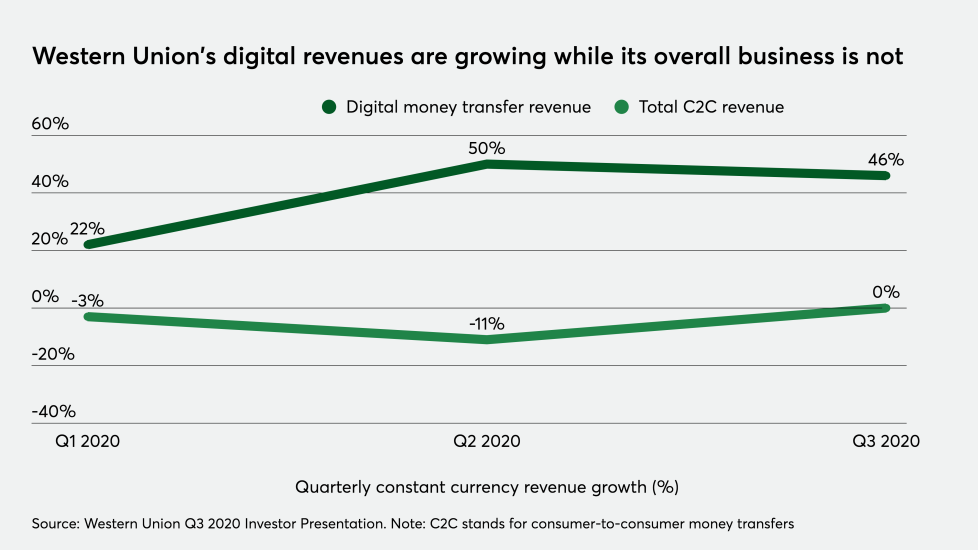

Before COVID-19, the cross-border money transfer industry was undergoing a gradual shift away from customers using local, walk-in agents to using digital channels — often in the form of mobile apps promoted by startups and fintechs such as

However, when the pandemic hit full-force and lockdowns closed many agent locations, the industry’s shift to digital accelerated quickly. Even as job losses rose among those sending money overseas, the demand from recipients kept money moving, including among legacy companies like

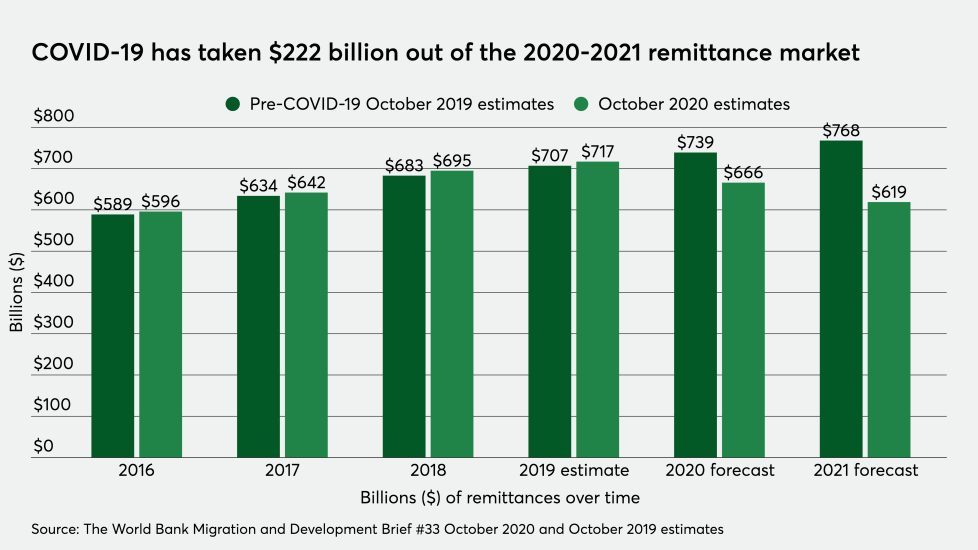

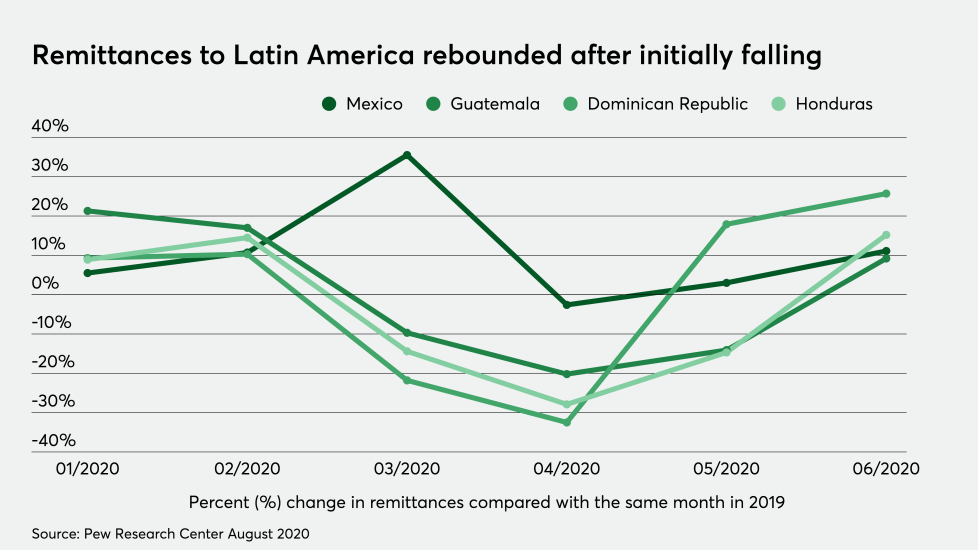

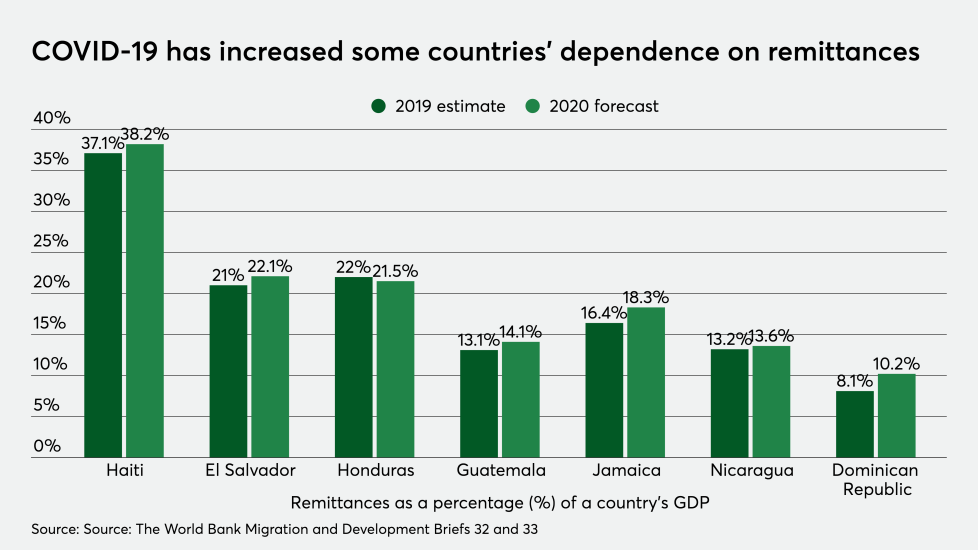

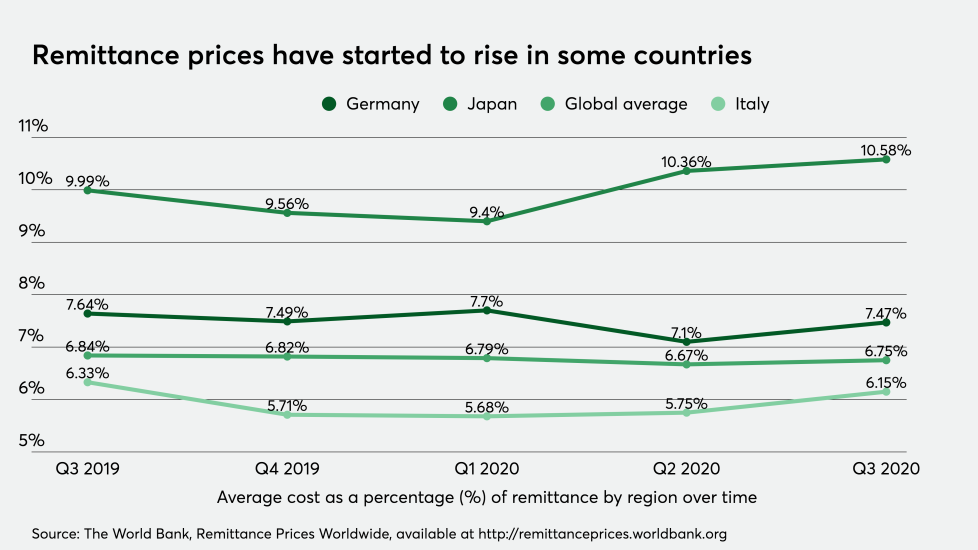

But that shift in demand wasn't enough to overcome the full effects of the pandemic. Here’s seven ways COVID-19 has impacted the remittance market.