Budget-tightening is prompting more state and federal agencies to expand the types of benefits distributed using prepaid cards, including unemployment and Social Security, as they look to reduce costs associated with cutting paper checks.

Some 30 states use prepaid cards to distribute unemployment benefits, and each touts the economic and practical reasons to make the switch from distributing checks. Cost associated with printing checks and buying postage can be in the millions, they say.

But while states may be cutting their expenses, many consumers who have their benefits deposited directly into prepaid accounts say fees applied to card use are eating away at their precious funds while issuers profit. Program managers and issuers insist, however, benefit cards represent a public service and are not a revenue-generator, as agencies have pressed them to keep fees as low as possible or avoid them altogether.

Indeed, JPMorgan Chase & Co., which issues prepaid cards to distribute unemployment benefits and manages the disbursement programs for 12 states, contends it has faced unwarranted scrutiny from the mainstream media and consumers regarding the unemployment cards it issues.

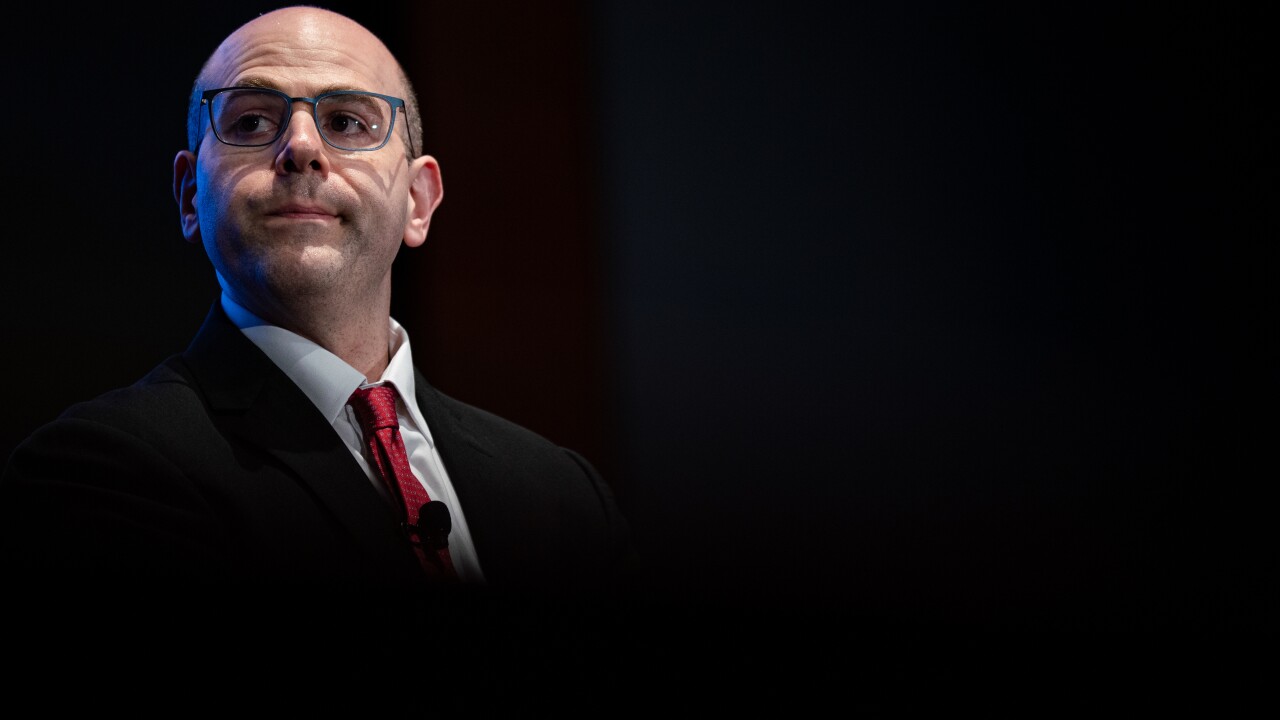

“We’re unfortunately an easy target in that space because we’re a big bank and it’s unemployment,” says Tracy Dangott, Chase vice president of public sector card solutions, tells PaymentsSource. “Any time you get charged any fee it becomes about the big bank going after your money.”

Dangott believes the criticism partly stems from being grouped into the same category as general-purpose reloadable debit card providers. “We look at [prepaid] very differently than they do,” Dangott says.

States deliver a request for proposals to issuers that documents the outlines a vendor must meet, according to Jeff Hentschel, a spokesperson for the Tennessee Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Chase issues the state’s prepaid unemployment-benefits card.

“Vendors will then bid on the contract, and the state selects the vendor based upon the bid and being able to meet all requirements,” notes Hentschel, who could not immediately provide examples of some of those requirements.

Tennessee and other states do not pay Chase, but the issuer does incur costs to operate the program so it needs to charge some fees to make up for those expenses.

There are not many differences between the fees Chase applies to unemployment benefit cards and those prepaid card providers apply to general-purpose reloadable prepaid cards. Unemployment cards are free and there is no reload fee since benefits are direct deposited into the card account.

Chase would prefer that recipients of unemployment benefits receive their funds via direct deposit into a demand-deposit account, Dangott says. “We advocate direct deposit because when you already have a retail-banking relationship with someone else, you don’t want our card,” he says.

The card is ideal for recipients who are “happy to have the service, a person who needs that service [for whatever reason],” Dangott adds. “That’s the customer we want.”

Chase views unemployment prepaid cards as tools that meet a public need, not as marketing vehicles, Dangott says. “It’s something we don’t promote very much when we do it,” he adds.

“People tend to forget these kind of programs cost money,” Adil Moussa, an analyst with Aite Group LLC tells PaymentsSource. “You have to pay for the cost of the plastic, customer service centers and workers and other expenses.”

In the end, the states make the final decision on the card’s fee schedule, which is why fees vary, Dangott says.

Chase provides recommendations and options for cardholders to access funds at no cost. “We pride ourselves on it; we make sure of it, and we then educate the cardholders on how to do it,” he adds.

The U.S. Department of the Treasury is taking a similar approach with a pilot that involves distributing 2010 tax refunds to reloadable prepaid card accounts (

Bonneville Bank, a subsidiary of Bonneville Bancorp, a Provo, Utah-based bank holding company, is issuing the cards. Green Dot Corp., which has an application to buy Bonneville Bancorp pending regulator approval, will help manage the pilot, which already is under way.

As states do, the Treasury Department sets the fee schedule for its cards and is testing cards with no or few fees. The monthly maintenance fee for some cardholders is $4.95. Some cards have an interest-bearing savings account feature in addition to the prepaid account.

The department will determine which combination of fees and features cardholders prefer before proceeding with a full rollout, Josh Wright, the director of financial access innovation in the agency’s Office of Domestic Finance, tells PaymentsSource.

“The Treasury Department is definitely not trying to make a profit off the cards,” Wright says. “We’re viewing this simply as another choice to provide people with a way to get their tax return and then have ongoing access to a basic financial account.”

Wright is unsure whether the program will expand beyond a pilot. If it does, the department would solicit bids from issuers to manage the program.

“We would use that competitive process to get fees as low as possible,” Wright says.

Indeed, fees have been a central issue regarding prepaid cards, which has prompted various legislative attempts to rein them in.

Proposed and recently enacted state and federal regulations regarding debit and reloadable prepaid cards have put card programs used for disbursing unemployment, Social Security and other benefits in serious jeopardy, Dangott says.

“I would say within two years, prepaid’s interchange potentially will be eliminated if not by regulation then by market practice,” he adds.

Reloadable debit cards are exempt from the so-called Durbin amendment in the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. But Dangott believes prepaid card interchange soon will come under attack much the way traditional debit card interchange did. If that occurs, it essentially would eliminate prepaid card programs that issuers manage for government-benefit disbursement, he adds.

“All of these states will either have to start paying for the program [which is free now], or they will go back to issuing checks. And it will be a reversal of the current trend,” Dangott says.

U.S. Sen. Robert Menendez, D-N.J., introduced a bill in December that would prohibit prepaid card providers from charging fees for card inactivity, balance inquiries, overdrafts and other activities. It also would require disclosure of fees issuers would charge customers.

The bill failed to come to vote last year, but Dangott suspects it will pass later this year.

“We will have to abide by that law, and that means we’ll go back to every one of our clients and ask, ‘what do we do now?’” he says. “We’ll have to ask the states, ‘do we charge you, or do we charge the cardholder?’”

The Menendez bill is asking prepaid card providers to charge a single, flat and fair fee for all transactions instead of multiple fees for what are considered “everyday activities,” according to Suzanne Martindale, Consumers Union associate policy analyst.

Consumers Union, publisher of Consumer Reports, is a Yonkers, N.Y.-based independent, nonprofit testing and information organization serving consumers nationwide. The body worked closely with Menendez on the bill.

“If you have a flat, monthly fee upfront, it gives consumers a chance to decide if they want the card,” Martindale tells PaymentsSource. “We want to see this for all types of prepaid cards.”

Consumers Union views the Menendez bill as a blueprint for the Consumer Financial Protection Board, which Congress created in the Dodd-Frank Act. The board will have the authority to regulate a wide variety of consumer financial products, and that may include reloadable prepaid cards.

“When you have federal regulations in place, then you have administrative enforcement mechanisms,” Martindale says. “If you have a bad apple out there, the board has the authority to go after them for violating their rules.”

Prepaid provider support for the Menendez bill appears mixed.

Martindale claims Green Dot is in favor of it to bring others in line with its low fees. “Green Dot has said what they don’t like is that they’re the good actors and get lumped in with the bad actors,” she adds.

Green Dot executives were unavailable for comment.

Dangott believes the government-benefits market has self-regulated itself in terms of fees. “I can’t go in and gouge and just market my way through it,” as opposed to what general-purpose reloadable prepaid card marketers can offer, he says.

“Professional procurement offices” that run complicated analyses of provider bids scrutinize Chase’s state contract proposals, Dangott says.

This sector has “self-regulated itself through competition, which is the way it should work,” he says.

Issuers and government agencies will continue to view benefit cards as a public service and a way to reduce costs. Impending regulation could result in unintended consequences for the sector.