Lemons or lemonade? How bankers feel about their environment

Cost-cutting blues

When asked about the change in focus, Wells Chief Financial Officer John Shrewsberry noted that this is not the first time the company has set a specific target for expense cuts. It also did so following its 2008 acquisition of Wachovia.

Still, Shrewsberry acknowledged that it can be difficult to find expenses that make sense to cut, since they are not adding sufficient value to the company.

"That is a cultural change — not that people haven't always thought that was important, but finding it and driving toward it, because it's not always obvious where it lies, that's the change," he said.

But we could spend the savings here …

Timing's right for online unit …

… Our timing? Not so much

The Riverwoods, Ill.-based firm

Four years later, the checking account is still available only to consumers who are already Discover customers. Discover Chief Financial Officer Mark Graf said Tuesday that the product's wider rollout has been delayed by ongoing regulatory issues related to Discover's anti-money-laundering program.

In a 2014 pact with the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., Discover agreed to establish a new anti-laundering compliance regime.

"It didn't seem a prudent decision on our part, when we were being asked to enhance that anti-money-laundering capability, to broadly launch a product that is the largest single product used for money laundering activity, that being a transaction account," Graf said at the Credit Suisse forum. "So we felt we should get our ducks lined up before continuing to really push that product."

Still a SIFI? No problem

Both of those credit card issuers have less than $250 billion of assets — a benchmark that has frequently been floated as an alternative to the current cutoff of $50 billion — while competitors including Capital One Financial sit above the quarter-billion-dollar threshold.

But Capital One CEO Richard Fairbank argued that his $345 billion-asset company has found a favorable spot — big enough to take advantage of its size, but not so big that it has to comply with certain regulations that apply to the largest institutions.

Fairbank said that the digital revolution is bringing bigger advantages to companies that have scale.

"Very purposefully, we have built a national business model for all the businesses that we choose to be in," he said. "When I look at the smaller banks, I don't see a big competitive advantage that they have."

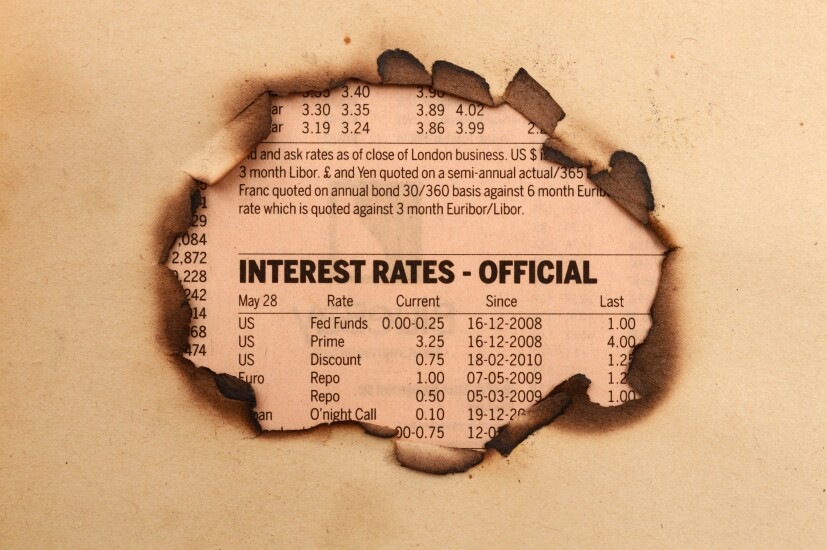

Rate hikes? No problem

Cybersecurity's drain on resources

During a presentation Tuesday, Jason Witty, its chief information security officer, said that U.S. Bancorp has invested heavily in cybersecurity in recent years and should see those costs flatten out in the future. But the trick with budgeting for information security is that you never know what will happen next.

"Being a chief information security officer is kind of like being a weather predictor, but it's like being a weather predictor on a planet where there's a new type of weather every quarter, and none of the old types of weather go away," Witty said.

To keep close tabs on its network, the $446 billion-asset bank monitors 3.8 billion events per day and processes approximately 1.3 petabytes of information. To put that context, imagine digitizing the entire Library of Congress, putting all of that text in storage, and then multiplying that by 20, Witty said. That's one petabyte.

Still battling the paper blob

Consider monthly bank statements. It's not printing and mailing them that's expensive; rather, it's the cost of maintaining a large system of storing, printing and mailing the paper that weighs on the bottom line, Dean Athanasia, co-head of consumer banking, said at the conference.

"Remember, it's not just [customers] going to automation, which is great for us," said Athanasia, who is also president of small-business banking. "But then we don't have to track it all the way through — we don't have to store it, we don't have to retrieve it."

There's also the matter of paper checks. Even as consumers move away from check-writing, favoring cards and mobile payments instead, many of the systems used to print and process checks remain in place.

"We may never get out of checks in the next five years," Athanasia said, noting that it takes "giant systems, printing and sending out checks, and check readers" to support the process.

Efficiency across the industry will improve once banks are able to "retire all the systems and technology" used in paper-intensive businesses, he said.