-

On eve of law's second anniversary, regulators face heavy scrutiny over how they will implement remaining Dodd-Frank rules. Many key regulations have yet to be seen.

July 13 -

The central bank on Wednesday said it discussed the Volcker Rule and proposed counterparty limits at a private meeting with the leaders of several big banks, including Brian Moynihan of Bank of America Corp.

May 2

WASHINGTON — A Federal Reserve Board proposal to enact strict limits on how much credit exposure the largest banks can have to a major counterparty has significant design flaws that could raise the cost of credit, according to new analysis by the Clearing House.

Large banks have been concerned about the plan since it was released in December, arguing the single counterparty credit risk limit is too strict and would cause them to rebalance their portfolios, reducing the liquidity of the derivatives and securities lending markets.

The Clearing House study is the first attempt to comprehensively quantify the impact the proposal would have. Surveying 13 of the largest commercial banks, the study concludes that the Fed plan would dramatically overstate the level of excess risk exposures.

"One of the key issues around the proposal itself is how credit exposure is measured. The current exposure method in the proposal, or CEM, overstates the underlying risk and we feel that this is not an accurate exposure measurement tool," said Bob Chakravorti, senior vice president and chief economist for the trade group.

The study also analyzed differences between the way the Fed and its foreign peers addressed counterparty risk.

"There seems to be a contrast to what's happening elsewhere such as in the European Union," Chakravorti said. "We should have some consistent global policy."

Under its massive Section 165 proposal, the Fed's plan would require banks with more than $50 billion of assets to adhere to a two-tier structure in how they limit their counterparty exposures.

All such institutions must comply with a Dodd-Frank 25% limit on exposure to a single counterparty, but the Fed has said it may apply a secondary limit of 10% to certain large firms to other major covered counterparties. The limit, which is set at the discretion of the central bank, will depend on the counterparty's size as well as the size of the bank itself.

Such limits are aimed at helping an institution manage its overall risk and avoid significant concentration to any single counterparty. While the industry supports the 25% limit, there is continuing concern about the 10% restriction.

"We would suggest that there should be more quantitative studies done before the 10% limit is implemented," Chakravorti said.

More broadly, the study argues the current exposure methodology the Fed is asking banks to use to calculate their derivative counterparty exposure is significantly flawed. It also disagrees with a requirement to substitute, or "risk-shift," exposures to third-party guarantors on a notional basis.

"Given the large difference between the proposed credit exposure methodology and the methodology being used today for risk management, we would recommend more quantitative analysis be conducted prior to implementation, along with more coordination with the international community," Chakravorti said.

The study claims that the Fed's methodology overstated banks' exposure 12 times more than if the central bank had used a different risk-sensitive internal model methodology, called the IMM, that is widely used among banks.

The analysis said the Fed's methodology did not recognize certain credit risk mitigation benefits that other alternative models generally accept. Such benefits include the use of legally enforceable bilateral netting agreements, collateral or a diversity of derivatives contracts in a bank's portfolio.

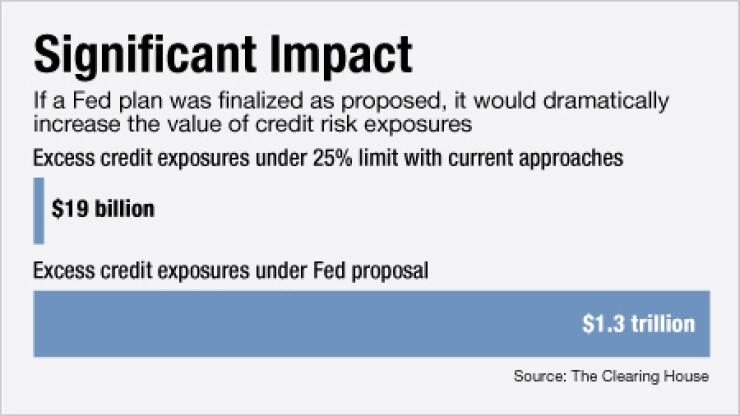

Across the 13 banks surveyed, the study found that if the proposal were finalized without changes, it would result in a significant number of credit exposures that surpassed the central bank's limits.

For example, at those institutions there were 100 incidents that would have violated the limits, valued at $1.3 trillion.

More than 40 of those incidents were between 100% and 150% of the proposed limits, and 27 incidents were more than 300% over the proposed limits, the study says. That's a huge spike compared with the eight incidents, which would be valued at nearly $19 billion, based on current approaches used.

The study argues that if certain aspects of the rule were adjusted to accurately reflect the true credit exposure of banking organizations, these excesses could be significantly reduced with less impact on the financial markets and economic activity.

For example, if the 10% limit were eliminated, the number of incidents would drop to 63 with an aggregate exposure of $665 billion.

The study says the requirement to risk-shift exposures to protect providers results in 25 extra exposure incidents. It also points to the Fed’s intent to subject central counterparties and non-U.S. sovereigns to the proposal.

The combination of factors "results in estimated exposure excesses to the 10% and 25% limit that are roughly 38 times those estimated employing the industry baseline," the study says.

These factors and others would harm the economy, the study says. "Market participants could be significantly negatively affected by any resulting lower liquidity in the derivatives and securities lending markets," it says.

That could include regional and community banks, corporate debt issuers, pensions, and government-sponsored entities. Because of the overstatement, all participating banks would have to reduce the notional amount of their existing derivatives outstanding by $30 trillion to $75 trillion, according to the report.

Because of antitrust considerations, authors of the study couldn't explain what measures banks would use to bring down their derivatives exposures, but said the runoff of existing positions as well as efforts by the industry to restructure and rebalance exposures would be "insufficient" to bring U.S. covered companies into compliance by the deadline.

As a result, the Clearing House made five recommendations, including urging regulators to drop their proposed exposure methodology in favor of the approach currently used by banks. It also said the Fed should remove the risk-shift requirement, eliminate the proposed 10% discretionary limit and exempt central counterparties and high-quality non-U.S. sovereigns from the rule.