-

Browser advancements made in recent months are allowing developers to bring check deposit to mobile sites.

June 17 -

Mobile remote check deposits are becoming table stakes, and mobile photo bill payment may be close behind. But concerns about image quality will need to be assuaged first.

February 1

Mobile check deposit, once a low priority technology for banks, has become one of the most sought out mobile banking app features. But along with popularity and increased use, the potential for fraud is emerging for smartphone check deposits.

A recent report from ath Power Consulting identifies remote deposit capture as

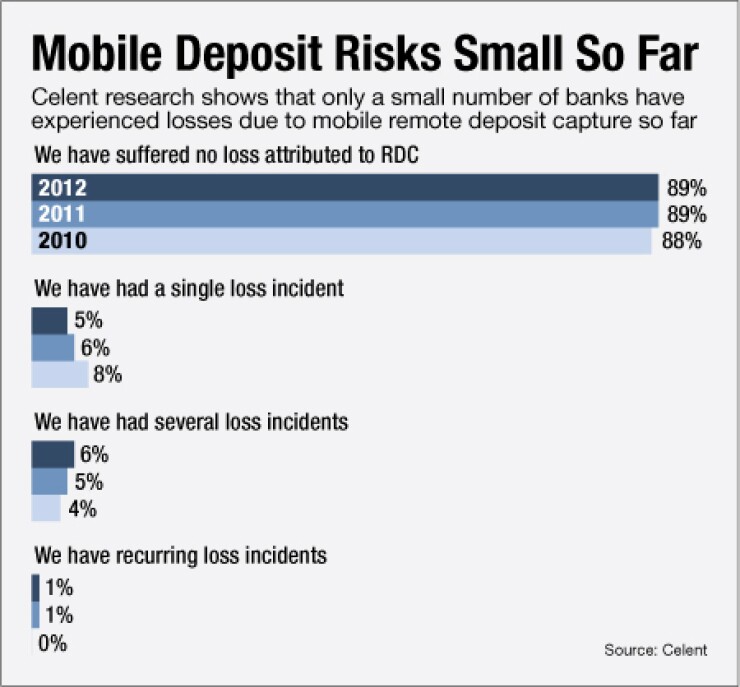

Banks are responding. Research from Celent shows that in 2009, 72% of surveyed financial institutions had no plans to offer mobile remote deposit capture (RDC). By 2012, only 18% were holdouts.

The high demand has challenged vendors of the technology. "There's a waiting list," says Bob Meara, senior analyst in the banking group of Celent. "At the end of the day, it will be commonplace."

To date, fraudsters have largely left mobile RDC alone. One reason could be the lack of a big payoff: banks often set daily deposit limits at $3,000 or less. Furthermore, Celent's 2012 data shows that about 90% of RDC deploying banks reported zero losses. Most that have suffered some loss have been larger institutions.

Still, evidence of crime committed through mobile RDC is slowly emerging. "There are some examples of customers double depositing," says John Leekley, founder and chief executive of remoteDepositCapture.com, an informational services company. "As is always the case with criminals, they are looking for new and different ways to exploit and game money from banks and consumers."

The Check 21 Act of 2004, which made it okay to create digital versions of paper checks for processing, spells out the rules required of check imaging, regardless of which channel the payment comes through. However, in mobile there is one notable difference that paves the way for new threats: the consumer holds onto the check, which gives them the power to serial deposit, by design or chance.

A

That could happen again.

"In mobile remote deposit capture, there is a risk that someone could intentionally deposit the check more than once," says Shirley Inscoe, a senior analyst at Aite Group.

A bad guy could open accounts at several banks and make multiple deposits with the same check. Or it could be an accidental crime: A customer could deposit a check from his mobile phone, and his spouse could spot the physical check on the counter and deposit the funds at a branch.

"In a world where anyone can deposit a check and keep the paper check, the risk multiplies," Inscoe says.

The risks are waking up companies to the importance of the check endorsement.

"The

Most banks' policies require a John Hancock, and Celent's Meara says it's normative for mobile RDC technology to detect whether the back of the check is endorsed (it doesn't commonly analyze handwritten signatures for authenticity).

There are potential vulnerabilities with that approach. A customer could hypothetically save the back of a check so he could image two different checks on his smartphone to commit fraud through mobile RDC.

Some financial institutions like USAA require depositors to endorse the item as a deposit only and provide the bank with an account number.

Such restrictive endorsements could help mitigate risk of double deposits, especially as the technology matures to detect and verify the handwritten scribble on the back of the check, according to Leekley.

The Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council

"Risk management starts with knowing your customer and establishing appropriate risk policies with limits," says Jim Ballagh, vice president of business development at Ensenta, a company that sells mobile deposit technology with added risk management tools.

With regulators

"Just about everyone is working on doing something," says Leekley.

Meanwhile, the industry collectively has been working on ways to prevent check double dipping by sharing deposit data among one another. Early Warning Services is building a database that will let bank participants receive real-time notice of duplicate checks.

"A slow and growing ability to detect duplicate items is emerging," says Meara.

The leader in imaging software for mobile check deposit, Mitek Systems, is one of many vendors taking note of the demand for features that are designed to help banks stay ahead of the bad guy.

"What we are hearing from a lot of customers is that they are looking for leadership on mobile RDC," says Michael Strange, CTO of Mitek. "That's not just about fast and accurate (software) but also for risk management."

To that end, Mitek recently enhanced its endorsement detection to score the likelihood the check is properly signed. Mitek is also cooking up restrictive endorsements in its labs.

Meanwhile, Ensenta, which white-labels technology from Mitek, is working with its partners to create additional real-time tools to mitigate against fraud. "We continue to work on technology to stay out in front of potential fraudulent usage and we have a number of initiatives under way that involve additional real-time analysis," says Ballagh.

The Ensenta software already examines more than 150 risk criteria, many of which aren't necessarily considered by the teller, says Ballagh. "There's a certain amount of risk review not necessarily done by the teller and perhaps that's one reason why we are seeing a fairly minimum amount of fraud."

Security vs. Usability

Banks struggle to find the balance of usability and strong risk measures.

"You want to provide customers with a great experience," says Ballagh. "A bank is trying to maximize the risk mitigation and customer experience at the same time."

Companies are working on improving mobile deposit ease of use, including alerting people when they should throw out checks. There are limits on what a bank can do, however. "Will you audit peoples' kitchens?" jokes Meara.

Meanwhile, mobile RDC 2.0 will

All things considered, some say mobile deposit is more secure than branch deposits. "If the financial institution has the right safeguards in place, mobile RDC is a safer way to deal with payments [than traditional deposits]," Leekley says.

"Historically, banks rely on tellers to have vigilance," Meara says. Mobile RDC