Westamerica Bancorp is finding growth awfully hard to come by these days.

The San Rafael, Calif., company has been stuck at roughly the same asset size for six years now, even though it has the capacity and desire to become much larger.

The reasons revolve around two important questions that many community bankers are asking themselves right now: Should I cut corners to grab market share, or should I sell to a bigger bank and be rid of this albatross?

-

The pace of bank mergers and acquisitions has slowed of late as bank stock values have plummeted, but expect it to pick up as 2016 wears on. Here's why.

March 8 -

Westamerica Bancorp. will close its branch in Upper Lake, Calif., after a failed effort to find another financial institution to take over the branch.

October 15 -

Some banks appear to be aggressively pursuing loan growth at the expense of profits these days. But banks like M&T and Westamerica say they are slowing things down, hoping the caution will translate into better credit quality in the long run.

April 20

In Westamerica's case, it has plenty of money to lend, yet it has allowed its loan portfolio to shrink rapidly over the last several years because it refuses to loosen its underwriting guidelines in order to win business.

It also has the capital to grow through acquisitions — if it could find the right bank to buy. Chairman and Chief Executive David Payne said that in the 26 years he has been running Westamerica, he has never seen a time when community bankers in his markets of northern and central California have shown so little interest in engaging in merger talks. It is puzzling, he added, given that competition for quality loans is as fierce as ever, persistently low interest rates continue to squeeze margins, and compliance and technology costs are threatening to bust many community banks' budgets.

"I see the returns on equity and the returns on assets they are generating," so it is surprising "that they wouldn't at least contemplate the possibility of selling," Payne said in a panel discussion of West Coast bankers at an investor conference in New York last week. "I'm hoping there's some catalyst out there that will cause smaller community banks to think about being acquired, clearing the forest a little bit, so that the marketplace might [become] a little more rational."

Until that time comes, Westamerica will continue to stand pat — just as it has done for much of the last six years.

The bank's total assets have barely budged in that time — from $4.9 billion in 2009 to $5.1 billion today — and Payne seems content to remain on the sidelines while rival banks try to grow assets by outbidding each other for loans.

It is an unusual approach for a publicly traded company in an industry where the choice is typically grow or die, but these are unusual times and, so far, investors have had little reason to complain.

Though its asset mix has changed radically in recent years, Westamerica remains more profitable than most banks, generating returns on assets and equity that are comfortably above industry averages. Its stock price, too, held up far better than most bank stocks during the economic downturn and still trades at a significant premium to its peers. Its Monday closing price of $48.52 was equal to roughly 3.1 times its tangible book value, compared with 1.6 times tangible book value for a peer group of small- and mid-cap banks in the western U.S., according to data from Sandler O'Neill & Partners.

Joseph Morford, an analyst at RBC Capital Markets, said investors have stuck with Westamerica despite the lack of growth, because they have great respect for Payne and his management team and trust that they will do what is best for shareholders. Even when stocks tanked earlier this year, Westamerica's rebounded faster than most and even trades higher now than it did at the start of the year.

"They are very conservative in terms of taking on credit risk and interest rate risk," Morford said of Westamerica's management. So "when investors get concerned about a possible recession and the economy, there is a flight to quality for stocks like Westamerica's that they feel comfortable owning knowing that they aren't going to be surprised by credit issues."

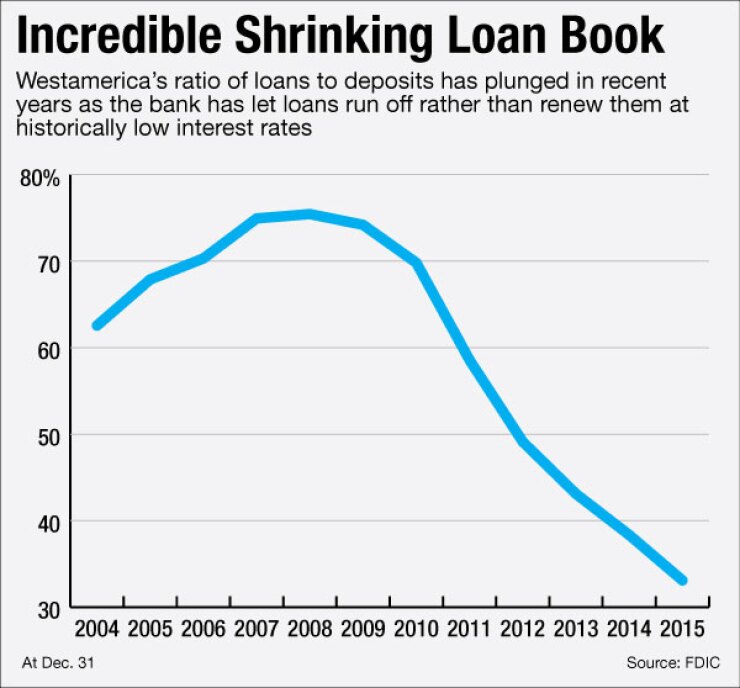

But how long can Westamerica keep it up? The bank has not stopped lending, but it has let scores of loans run off in recent years rather than renew them at historically low interest rates. The result is that the bank's loan-to-deposit ratio has fallen from 74.19% at the end of 2009 to 33.1% at the end of 2015. To put that in perspective, the industry average for commercial banks with $1 billion to $10 billion of assets was 84.66% at Dec. 31. For all California-based banks it was 83.91%, according to Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. data.

Aaron Deer, an analyst at Sandler O'Neill, said he has a "sell" rating on Westamerica's stock, partly because it already trades at a high multiple but also because he is concerned about its growth prospects.

"I don't want them overstepping on the risk side, but I would certainly like to see them grow their loan book," Deer said.

He would also like to see Westamerica return to buying banks, noting that the bank has a track record of making acquisitions "very profitable for shareholders." Westamerica bought nearly a dozen banks in the 1990s and early 2000s, but it has not made an acquisition since taking over failed banks in 2009 and 2010. Its last open-bank acquisition was in 2005, when it bought National Bank of the Redwoods in Santa Rosa, Calif.

Payne did not respond to requests to be interviewed for this story, but his frustration with the state of bank M&A was evident at the investor conference hosted by RBC Capital Markets.

While activity has been brisk in some other parts of the country, it has been quiet in northern and central California, an area that is home to many small, privately held banks. Payne said many of these banks feel "no real pressure" from investors to merge with larger players, so they are choosing to remain independent.

He also said that it is the community banks — not regional or large ones — that are most guilty of stretching on loan terms in order to capture loan business.

"I'm just amazed that we can have an economy growing a couple of percentage points and I'm looking at community banks growing their loan books at 10%, 12%, 14% linked quarters," Payne said. "I'm trying to figure out how that can be accomplished without making some ultimate compromises, be it pricing or a combination of pricing, terms and underwriting."

Still, even Westamerica may have to make compromises at some point, Payne acknowledged.

For several years, the bank has been loading up on shorter-duration securities so it could quickly ramp up commercial lending when interest rates finally increased. But Payne said that "if interest rates stay down for an extended period of time there will have to be some compromise on that. I think ultimately we'll do some lending, diversify our strategy and perhaps inch out a bit."