Banks are pushing back against a new report that continues to paint a negative picture of bank arbitration clauses just as the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau plans to restrict such agreements.

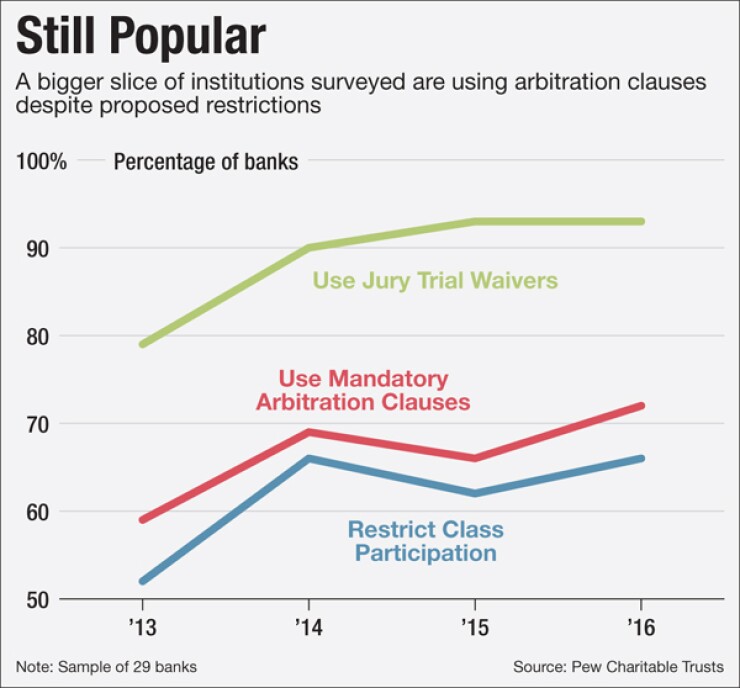

The Pew Charitable Trusts released data on Aug. 17 with results from surveys of both banks and consumers about the use of arbitration agreements. It found that, despite the looming restrictions, banks have actually increased adoption of mandatory arbitration clauses, with 72% of 29 banks included in the study using them for checking accounts, up from 59% in 2013.

In addition, 89% of consumers surveyed said they believe they should have the right to participate in group lawsuits, which mandatory arbitration clauses prohibit. The survey also found 95% of consumers thought they should be able to bring cases to a judge or jury.

-

WASHINGTON Community banks and credit unions would be forced to stop making short-term, small dollar loans if the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau's payday lending proposal is adopted, two trade groups said Monday.

June 27 -

Banks, credit card companies and other financial firms are strategizing ways to stave off higher legal bills they expect from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureaus proposal to limit the use of arbitration clauses, which is likely to open the floodgates to class action lawsuits.

June 30 -

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau's proposal to limit the use of arbitration clauses came under attack Wednesday for potentially raising costs and liability for financial firms.

May 18 -

The U.S. Department of Education has proposed regulations to strengthen a rule against predatory practices by post-secondary institutions.

June 20

But industry representatives raised questions about the methodology used in the report, including whether respondents were asked leading questions. They disputed Pew's findings on consumers wanting the ability to seek court resolutions of disputes rather than just arbitration, based on questions from a telephone survey with roughly 1,000 consumers.

"The survey questions are leading and they didn't lay a foundation for the consumers to know the truth, namely that class action lawsuits rarely are of any benefit to consumers," said Alan Kaplinsky, who leads Ballard Spahr's consumer financial services group and helped spur the widespread adoption of waivers that prohibit class participation over three decades ago.

The report came in advance of the CFPB's finalizing a proposal to restrict arbitration agreements. At the heart of the CFPB's plan is a move to remove banks' ability to stop consumers from forming or joining class actions through arbitration agreement.

The Pew data also looked at how banks have specifically included class-action waivers in account agreements, with 66% of the 29 institutions including such waivers this year, compared to 52% in 2013. The study said even banks without mandatory binding arbitration clauses can still require customers to waive their right to a jury trial. Of the 29 institutions, 93% included such waivers this year, compared with 79% in 2013, the study said.

"Consumers of all political stripes want access to the justice system, whether it's being able to take your bank to court or being heard before a jury," said Thaddeus King, an officer at Pew's consumer banking project. "If there's no way for consumers to go to court there's less incentive for financial companies to comply with the law."

But legal observers said the Pew survey was too skewed toward going to court as an option for consumers without indicating to respondents that arbitration has benefits.

Robert Jaworski, a member of the financial industry group at the law firm Reed Smith, said Pew read consumers two sets of two legal options but did not present them with the option of going to arbitration.

"Since most consumers are not familiar with arbitration, I would expect the results would still favor going to court," Jaworski said. "If it was explained to consumers what arbitration is and that studies, including the one undertaken by the CFPB, have shown that arbitration is faster, more efficient, less time-consuming for the consumers and leads to more favorable outcomes for consumers than going to court, I would expect the results would be different."

Yet in response to the criticism, King said consumers were asked the same question in two different ways — to determine if it would still elicit the same response — although they were not necessarily asked about arbitration. One version would be: Should the right to pursue a legal action be taken away? The other version would ask whether banks should be able to restrict the right to sue.

"The results are virtually identical either way you ask the question," King said. "I really don't think we could have been clearer."

For decades, banks have included language in consumer agreements that require consumer disputes be resolved through arbitration rather than a legal challenge in court. In many cases, banks have banned the ability of consumers to sue as a group, Pew found.

The CFPB's plan to limit arbitration clauses, which would allow consumers to bring class actions, is highly controversial given that it would impact millions of consumer contracts and cover roughly 55,000 companies. The industry has threatened to sue over the pending rulemaking, but that can only happen after a final rule comes out, which is estimated to be in the second half of 2017.

In anticipation of the rules, some companies have considered

But the Pew research shows that those supporting a crackdown on arbitration are continuing to try to build the case in the face of potential challenges.

"We do hope that the CFPB will consider our research because it bolsters their case for making this rule," King said.

The Dodd-Frank Act gave the CFPB the authority to prohibit or impose limitations on the use of arbitration clauses but only if such measures are "in the public interest" and "for the protection of consumers." The law also required the agency to carry out a study of arbitration, and states that any resulting regulation must be consistent with that study.

But industry representatives have used the bureau's own arbitration study to show that arbitration is in the public interest, and that the CFPB's findings do not align with the bureau's own proposal. They have seized on agency data showing that consumers received an average of $5,389 in arbitration, compared with just $32.25 from class action settlements. The disparity in payouts is being used to challenge the CFPB's arbitration plan.

Yet Pew found that many consumers would be prepared to have their day in court if given that chance. The study said 23% of respondents to its survey said they would consider filing a lawsuit against a bank or financial firm over a dispute. That number would mean potentially millions of lawsuits would be filed against a wide swath of companies if consumers were not limited by the waivers.

Jaworski said most consumer complaints are resolved long before a consumer might consider legal action either by a bank waiving a disputed fee or by providing the consumer with additional information. Both the CFPB and state banking agencies also help resolve issues by accepting consumer complaints when disputes are not settled, he said.

Others said consumers may be disappointed with the ability to seek court damages since the litigation process can be rife with problems.

"It definitely gets people angry on both sides but pursuing class actions may not be the best thing for consumers," said Phil Stein, a partner at Bilzin Sumber. "Consumer advocates would love to feel there is greater access to the courts, but a lot of lawsuits filed on an individual basis are costly and self-defeating for consumers."