The finance industry pushed back against a proposal by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Thursday that would ban arbitration clauses in consumer contracts, saying it will pave the way for a flurry of class-action lawsuits and result in higher prices for products and services.

The proposal drew criticism across the various affected industries, including most types of consumer lending with the exception of mortgages. Industry lawyers made it clear at a field hearing in Albuquerque, N.M. that they are expecting a fight.

"Ultimately, there's a high likelihood that the rule will be challenged," said Quyen Truong, a partner at Stroock & Stroock & Lavan LLP, and a former assistant director and deputy general counsel at the CFPB. "I think the impact will be tremendous and the CFPB recognizes that internally because it will increase class actions, which is a big cost in terms of litigating."

-

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is set on Thursday to issue a proposal that would ban the use of arbitration clauses that prevent consumers from bringing class action lawsuits. The proposal on arbitration is a major setback for the financial services industry, which will face potentially higher expenses to defend lawsuits.

May 5 -

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is expected to issue a proposal Thursday that would limit the use of arbitration clauses on millions of financial contracts from cellphones to credit cards to checking accounts. Here are key areas to look at when the plan is released.

May 3 -

Evidence points to thousands of arbitrations for individual claims in recent years, and there likely would have been more if not for negative publicity about arbitrations.

November 20 -

Banks say the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau plan to ban arbitration clauses for individual claims will aid trial lawyers, while consumer advocates say the move is overdue and may not go far enough.

October 7

The proposal would still allow companies to offer arbitration as a way to resolve disputes. But industry lawyers said by allowing consumers to bring class actions, particularly over small-dollar amounts, the CFPB had opened the flood gates to class-action suits. Companies cannot afford to set aside reserves for class-action litigation and operate an arbitration process.

"I believe most companies will simply abandon arbitration altogether because of the cost-benefit analysis," said Alan Kaplinsky, who leads the consumer financial services group at Ballard Spahr. "Consumers will pay for this in the form of higher prices and reduced services."

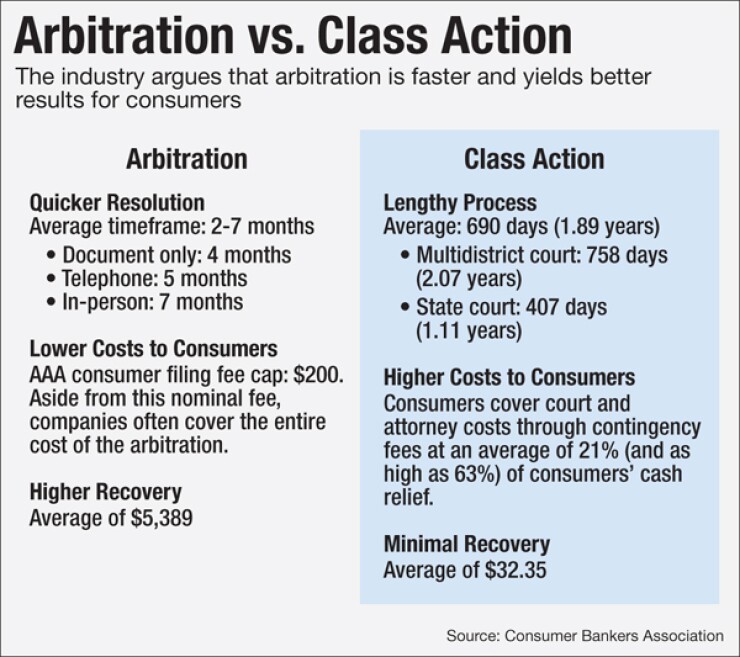

Speaking at a panel at the hearing, Kaplinsky listed the benefits of arbitration including that recovery amounts for consumers are higher, costs are capped at $200, and the timeframe for resolution is less than five months.

The CFPB's own study of arbitration found that consumers received an average of $32.25 from class actions that were analyzed, compared with an average of $5,389 in arbitration.

But the CFPB's 728-page study found that consumers rarely file individual disputes involving financial products or services in any forum.

CFPB Director Richard Cordray defended the plan during the hearing, arguing it was unfair to force consumers through arbitration.

"This practice has evolved to the point where it effectively functions as a kind of legal lockout," he said. "Companies simply insert these clauses into their contracts for consumer financial products or services and literally 'with the stroke of a pen' are able to block any group of consumers from filing joint lawsuits known as class actions."

Deepak Gupta, a founding principal at the law firm Gupta Wessler and a former senior counsel at the CFPB, said few consumers file for arbitration and the amounts are so small that they have no redress for wrongdoing.

"Arbitration doesn't move small-dollar claims to a faster, cheaper forum," Gupta said. "Instead it kills those claims. Those claims simply disappear."

Cordray said consumers often do not understand the agreements and have a tough time going up against a financial firm.

"When faced with the daunting prospect of spending considerable time and effort to recoup a $35 fee or even a $100 overcharge, it is not hard to see why few people would even bother to try," Cordray said.

Even Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton weighed in on the proposal, saying she plans to protect consumers from unfair and deceptive practices.

"Mandatory arbitration clauses buried deep in contracts for credit cards, student loans, and more prevent American consumers from having their day in court when they've been harmed," Clinton said in an emailed statement.

But Republican lawmakers voiced their opposition.

"Unfortunately, we have yet another example of an unelected, politically motivated, single director choosing what he thinks is best for the American consumer," Rep. Randy Neugebauer, R-Texas, said in an emailed statement. "Today's proposal is a clear win for class-action trial lawyers who reap unseemly recoveries, while consumers recover pennies on the dollar."

The impact of the proposal on consumers is important and could be used to challenge the plan.

The Dodd-Frank Act gave the CFPB the authority to prohibit or impose limitations on the use of arbitration clauses if the bureau finds that such measures are "in the public interest" and "for the protection of consumers," and if the findings are consistent with its study.

Industry representatives have used the bureau's study to try to bolster their claims that arbitration is in the public interest, and that the CFPB's findings do not align with the proposal.

"A challenge to the proposed rule would come under the three prongs embedded in Dodd-Frank," said Walter Zalenski, a partner at BuckleySandler.

The proposal includes extremely broad language covering roughly 50,000 firms, including banks, credit unions, credit card issuers, certain auto lenders, auto title lenders, payday lenders, private student lenders, loan servicers, debt settlement firms, foreclosure rescue firms, prepaid card issuers, installment lenders, money transfer services and certain payment processors.

There also are crucial issues related to the practical implementation of the proposal.

"Companies need to look at their contracts and think about how they want to proceed, and if they would structure agreements differently beyond simply striking the provisions preventing class actions," Truong said.

Arbitration agreements have been prohibited by Congress from being used in residential mortgages and home equity lines of credit and in connection with certain loans to servicemembers.

There is a 90-day comment period for the proposal, which is expected to go into effect next year.