The Wellsgate-related questions keep multiplying for other banks.

Here's the latest example: Bank of America said Tuesday it

B of A executives were asked that specific question and gave a multilayered response during a Monday morning conference call about its third-quarter earnings.

Deposits are a big reason for all those branches, Brian Moynihan, B of A's chairman and chief executive, said during a conference call. B of A, like other big banks, has seen deposits swell as customers look for a place to park money amid rock-bottom interest rates. That creates excess liquidity now, but those deposits will become extremely valuable if interest rates rise and the economy rebounds, Moynihan argued. B of A generates a huge amount of its deposit-gathering through branches.

"About 30% of deposits still go through the teller line still today," Moynihan said. "You have to be ready and able to serve in all dynamics. So what we continue to do is optimize the branch structure."

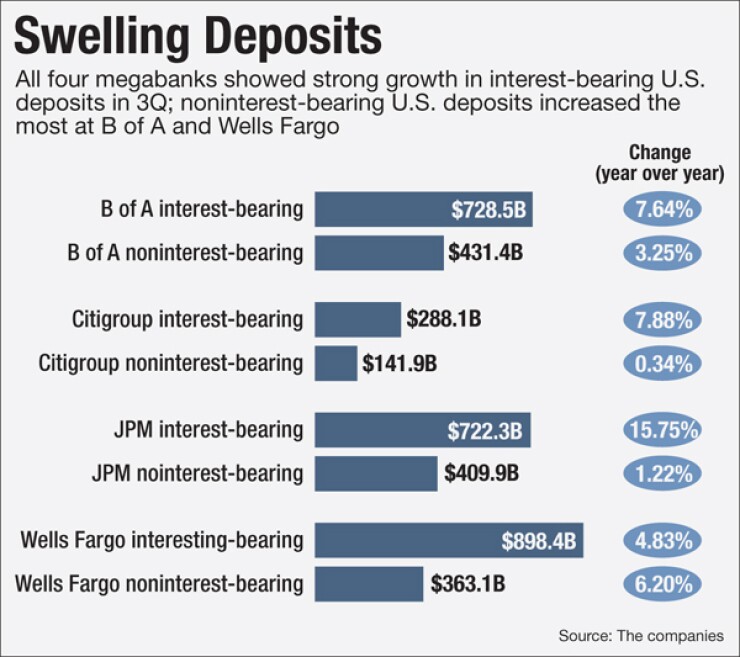

B of A's deposit-gathering machine went into overdrive in the past year. Noninterest-bearing deposits in the U.S., the most-coveted deposit type, rose 3.25% to $431.4 billion in the third quarter. Total deposits soared 6% to $1.2 trillion in the same year-over-year period.

The three other megabanks — JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup and Wells Fargo — all posted growth in noninterest-bearing and interest-bearing deposits for the same period, though the strength varied by bank. (See related chart)

Moynihan said he expects a big portion of B of A's deposits to stay with the bank even when rates ultimately rise. Many of B of A's customers use the bank as their platform to pay bills and conduct other routine transactions; they also have paychecks directly deposited into B of A accounts. That money isn't going to chase a higher interest rate at another bank, he said.

That's a sound argument, one analyst said in an interview following the conference call.

"Most of the new deposits coming in are customers' primary operational checking accounts," said Justin Fuller, an analyst at Fitch Ratings. "They're noninterest-bearing, and those tend to be less rate-sensitive, and they tend to stick around a bit more."

But B of A still operates 4,681 branches, third only behind Wells Fargo and JPMorgan Chase. And investors are pressing big banks to keep cutting costs. Is B of A's deposit-collecting performance enough to justify such a large branch network in an era when mobile apps are also credited with feeding deposit growth, especially at big banks?

Indeed, B of A on Monday touted its number of mobile-banking users, which it said rose 16% from the third quarter of 2015 to 21.3 million in this year's third quarter.

Mike Mayo, an analyst at CLSA, acknowledged on the call that B of A has reduced its branch count from 6,000 in 2010 to about 4,600 today.But the company could boost savings by closing more offices, he said.

Moynihan replied that the rise of mobile banking and greater branch usage are linked.

"We need those branches to receive those mobile-phone customers," Moynihan said. "Why are they coming? Usually for a much more important financial transaction to them than handing us a check for deposit."

That reference to other products might sound a little bit like the advantages Wells Fargo touted at its branches, raising other concerns.

Wells has 6,100 branches nationwide, the most of any U.S. bank, and it might have to close more than 1,000 of those branches for two reasons, Mayo had said last week in a research note. One is that branches were at the center of former Chairman and CEO John Stumpf's cross-selling strategy. Additionally, new CEO Tim Sloan last week

"Less reliance on the branches might ease any extra pressure to sell more products in this low-rate environment," Mayo told B of A executives on the call Monday.

Wells Fargo's issues don't apply to B of A, Chief Financial Officer Paul

In response to a question from NAB Research analyst Nancy Bush about how B of A's "methodology is different from what produced the problems at Wells Fargo, Donofrio said his bank's sales practices are different.

"To really answer that question you just have to have a better appreciation for how we run Bank of America," Donofrio said. "It truly really does start with our purpose, which is to help customers better live their financial lives."

JPMorgan and Citi both said last week that they have reviewed their operations for any signs of employee misconduct or of excess pressure on branch workers to manage to metrics. B of A executives did not indicate whether they have conducted a similar review.

B of A is built on the premise of "responsible growth," meaning that the bank will only sell additional products to customers when they need them," Donofrio said. "It's not about the number of products that we open."

The discussion ended inconclusively Monday, but it made two things as clear as ever: bank executives will continue to get probing questions this earnings season about sales practices and ethics, and the Wells scandal has added a whole new dimension to questions about the vulnerabilities posed by large branch networks.