-

As more banks work with ailing borrowers to relax the terms of their debt, a debate is brewing over how lenders classify restructured loans.

August 24 -

Citigroup Inc. managed to work out problem mortgages with more than 16 California borrowers for every home in the state it foreclosed on last quarter. The odds were considerably worse in Vegas.

August 25 -

Last month, the volume of private-label securitized mortgages that were liquidated through foreclosure was nearly as high as the amount that defaulted for the first time, according to Amherst Securities Group LP. The pace of first-time defaults in this sector has been falling since January, Amherst's data showed. If the trend persists, liquidations could soon be outpacing new defaults.

August 19 -

As Washington continues to debate policy options for reducing foreclosures, banks and servicers are struggling to deal with the glut of homes they are taking over when homeowners cannot make their mortgage payments.

January 21

Pick up just about any city's newspaper or turn on any news show, and if the topic is real estate, the banking industry is likely being lambasted for foreclosing on troubled homeowners.

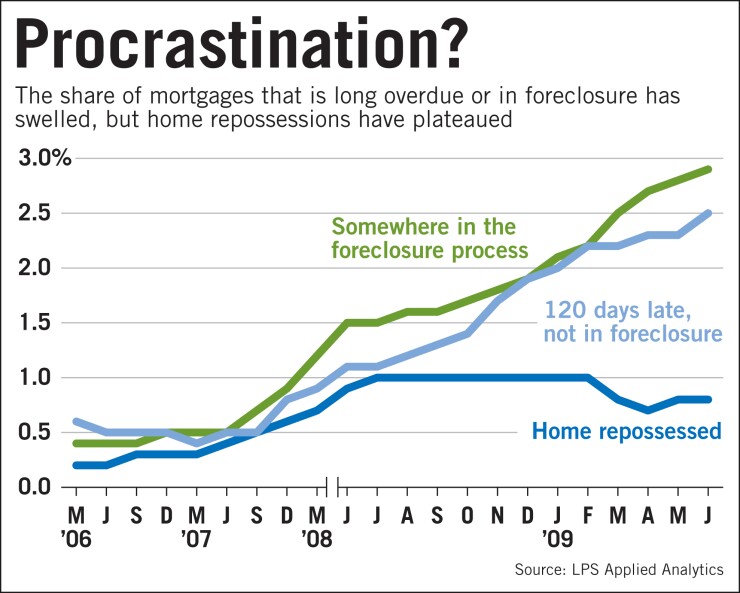

But industry data and anecdotal evidence suggest banks and servicers have been dragging out the process — not rushing to kick people out of their homes.

Granted, the deferrals may not be motivated by compassion, or even political pressure. Rather, banks and mortgage investors want to avoid repossessing hundreds of thousands of homes, which would produce losses and hits to capital.

"The goal is to hold off on foreclosures and take losses as slowly as possible to keep balance sheets up," said Deborah Voelz, the chief financial officer of National Asset Direct Inc., a New York buyer and servicer of distressed loans. "Everyone is looking at what the ultimate loss is going to be and whether it makes sense to hold off another year or two and mitigate the results."

The foreclosure process — and it is a process — now takes, on average, 18 months to two years, up from 15 months a year ago, according to Amherst Securities Group LP. Backlogs in county courts and at servicing companies, along with local government moratoriums, have contributed to the delays. But plenty of signs indicate that the mortgage companies themselves are in no hurry to seize their collateral.

Rick Sharga, a senior vice president at RealtyTrac Inc., an Irvine, Calif., company that monitors foreclosure filings, said banks often start proceedings but then decide "they don't want the property" and suspend the process indefinitely.

Of the 2.3 million homes that received foreclosure notices last year, one-third had been repossessed by yearend, according to RealtyTrac.

Banks also "are allowing borrowers to be delinquent for longer and longer periods of time before initiating foreclosures," Sharga said.

Tom Booker, a senior vice president in the default information unit at First American Corp. in Santa Ana, Calif., concurred. "There are borrowers who are six or eight months in default; they may have exhausted their workout options; but they're put on a forbearance plan because it's an interim to a final resolution, which is foreclosure," he said. "Banks don't want to take the losses now."

Deferring foreclosures could have bottom-line benefits, experts say. With fewer foreclosed properties hitting the market, housing prices have rebounded slightly. Moreover, properties might recover more of their value later on, so by waiting, banks may be able to cut their ultimate losses.

"Everybody is waiting to see what the market is going to do from a property price perspective," Voelz said. "At some point, they have to liquidate these assets."

How banks account for delinquent mortgages is the subject of ongoing debate among regulators, bankers and auditors.

Darrell Duffie, a finance professor at Stanford University's Graduate School of Business, said accounting rules give banks plenty of leeway to determine when to take losses.

"Banks are believed to be carrying a lot of loans at accounting levels well above their true market value," he said. "But once a property goes into foreclosure, their options have disappeared."

Timothy Ward, the deputy director of the Office of Thrift Supervision, went so far as to send a letter to chief executives in May reminding them that banks must account for losses when a loan is 180 days or more past due.

Charging off loans "only at foreclosure or when deemed uncollectible" is considered "weak" and not in accord with generally accepted accounting principles, Ward reminded bankers.

"This is the challenge the big banks have," said Fred Cannon, the co-director of research and chief equity strategist at KBW Inc.'s Keefe, Bruyette & Woods Inc. in New York. "They're supposed to take the loss at 180 days, but the initial chargeoffs aren't that much and then we're seeing big REO losses" (when a loan has been reclassified as "real estate owned").

Robert Simpson, the founder and president of Investors Mortgage Asset Recovery Co. LLC, an audit and fraud analysis firm in Irvine, said bankers have little incentive to realize probable losses until forced to do so.

"No one is encouraging banks to quickly book $75 million in losses and then take the heat for it, since they wouldn't have a job for very long," he said.

Standard & Poor's Corp. said Tuesday that its S&P/Case-Shiller index of national home prices rose 2.9% in the second quarter from the first. It was the first sequential rise in the index in three years. Compared to a year earlier, the gauge dropped 14.9% — a slower year-over-year decline than in the first quarter.

But in a note to clients, economists at Morgan Stanley wrote, "we do not believe that prices are actually improving for any part of the housing market, except possibly certain foreclosure markets due to a shortage of foreclosed inventory from the recent drop-off in liquidations. … This drop-off has nothing to do with fewer people becoming delinquent. … Instead, it has to do with banks and servicers reducing the rate at which they take back the properties."

Data released last week by the Mortgage Bankers Association showed delinquent loans growing at a brisk pace. In the second quarter, roughly 4.2 million borrowers were 90 days or more delinquent on their mortgages (a delinquency rate of 9.24%, up from 6.41% a year earlier), the trade group said. By contrast, foreclosures were initiated on just 612,000 homes (a foreclosure start rate of 1.36%, up from 1.08% a year earlier).

Michael Brauneis, the director of regulatory risk consulting at Protiviti Inc., a unit of Robert Half International Inc. in Menlo Park, Calif., said that, despite the high redefault rate on modified loans, banks now see an advantage in modifying instead of foreclosing "because it cures the delinquency and they may get par value out of the loan, if property values are stable. Even if they get [only] a few payments, if property values go up, they could do a bit better once they take out the borrower."

The flip side is: "The more foreclosures there are, the worse the losses become down the road," he said.

Though deferring foreclosures may help bridge a period of depressed revenues, losses still must be tallied eventually, said Cannon of Keefe Bruyette.

"One of the oldest lines in banking is 'the first loss is the best loss,'" he said. "That's what most lenders believe, but the question is, are they abiding by their own rule?"

Bill Garland, a senior vice president at Fiserv Home Retention Solutions, a unit of Fiserv Inc. in Brookfield, Wis., said many large banks have cut back on loan-loss reserves because they now see a rebound in housing prices, a move he called possibly shortsighted.

"People want to believe we're at the bottom, even though there's still a lot of REO inventory coming our way," he said.