-

Black and Latino borrowers received government-backed loans insured by the Federal Housing Administration or guaranteed by the Department of Veterans Affairs significantly more often than white borrowers, raising concerns about redlining, a new study has found.

July 24 -

The Federal Housing Administration says April foreclosure statistics from Lender Processing Services were inaccurate.

June 29 -

The Federal Housing Administration announced plans Friday to expand a program that encourages the sale of distressed mortgages to new investors.

June 8

Accentuate the positive.

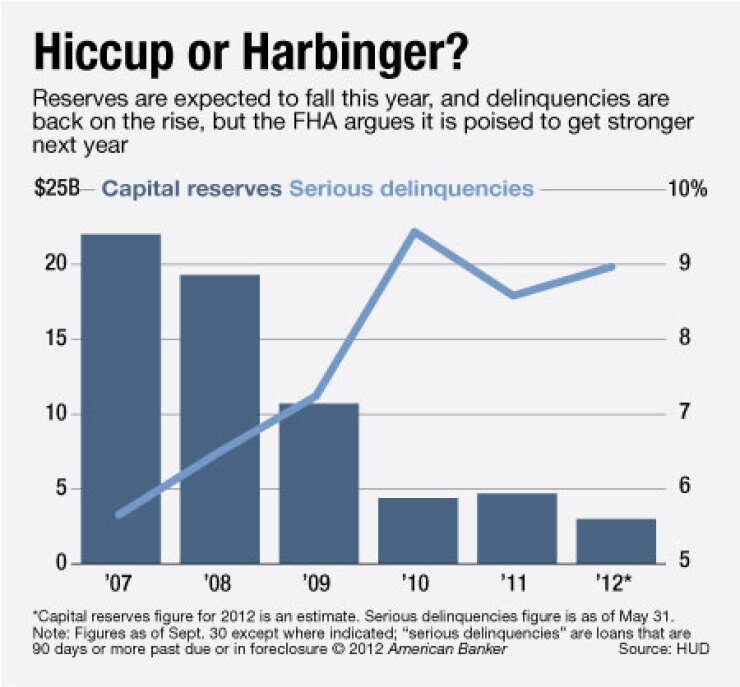

That's Job One at the Federal Housing Administration, which is touting itself as a turnaround story — a $3 billion surplus, no need for a government handout this year and an improving credit profile — ahead of acting Commissioner Carol Galante's confirmation fight on Capitol Hill.

Agency critics paint a gloomier picture. The FHA has embarked on a desperate attempt to raise capital through settlements with major banks, sales of severely delinquent loans and higher insurance premiums on new borrowers, they say. Its reserves are going to fall compared with last year, delinquencies are on the rise and foreclosure delays by the largest mortgage servicers have helped it avoid paying out new claims, the FHA's data show.

"Like any insurer, FHA is collecting a lot and not paying out a lot in claims," but the good times could end abruptly, says Clement Ziroli Jr., president of First Mortgage Corp., an FHA lender in Ontario, Calif.

Though FHA's current book of business will perform substantially better than loans written before 2009, the agency may have tried to recapitalize too quickly through higher premiums, Ziroli says. It could get stuck if borrowers with lower credit scores and smaller downpayments ultimately can refinance out of FHA, he says.

FHA only averted a government bailout this year through

"FHA is exhibiting characteristics of an entity looking for capital anywhere they can find it," Boltansky says. "They are looking high and low for extra cash."

Officials with the Department of Housing and Urban Development, which oversees FHA, are emphasizing the $3 billion in reserves in their push to get Galante confirmed to head the agency. Galante has been acting head of FHA for the past year and has taken steps to improve credit quality. FHA's finances are expected to become political fodder when Congress revisits her confirmation after its summer recess.

Nate Shultz, a senior policy advisor to Galante, cited a 75-basis-point increase in insurance premiums in April, to 1.75% of the loan amount, for helping shore up FHA's reserves.

"Primarily the increase in premiums and some enforcement mechanism like recouping losses through the foreclosure settlement helped us end up being better off than the budget," Shultz says. "It doesn't mean we're out of the woods yet, and we still have challenges ahead, but we've shown that all of the critics aren't entirely accurate."

Still FHA's projections are volatile. As recently as November the agency predicted it would end this year with nearly $12 billion of surplus reserves, but in February FHA was expected to ask for a $688 million taxpayer subsidy.

The discrepancy can be blamed on accounting requirements by the Office of Management and Budget, Shultz says. OMB required FHA to transfer $9 billion from the agency's capital reserve account to its financing account, leaving it with $3 billion in its capital reserves for its fiscal year that ends Sept. 30, he says. (It reported nearly $5 billion of reserves last fiscal year.)

In February, the Obama administration projected in its budget proposal that FHA's mutual mortgage insurance fund's capital reserve account would be depleted by next year. The account still has a capital reserve ratio of under 0.3%; Congress requires that the capital reserve ratio be at least 2%.

Brian Chappelle, a partner at consulting firm Potomac Partners and a former FHA official, has estimated the premium increases brought in an additional $10 billion this year.

"FHA is collecting the highest premiums in its history, which should have a positive impact barring the economy having more serious problems," Chappelle says.

Perhaps more surprising is how much FHA has benefitted from

Many of FHA's seriously delinquent loans — those that are 90 days or more past due — have not yet gone to claim because of the slow foreclosure process; the agency has reserved for such claims, Shultz says.

So far this fiscal year, FHA has paid 203,402 claims on residential loans, down 21% from a year earlier,

"While FHA's capital outlook may be better than it was six to nine months ago, it doesn't mean it will be consistent given that foreclosures are going to increase," Boltansky says. "The full impact of foreclosures is not being reflected at this point in time."

The agency also expects serious delinquencies from the wretched 2005 through 2009 vintage origination years to decline as servicers offer distressed borrowers loan modifications, short sales and other alternatives to foreclosure. Such loans now make up less than 16% of FHA's total portfolio.

FHA's performance also has improved partly because it insures more loans with higher credit scores and higher loan limits that, the agency says, reduces its overall risk.

More than half of the 4.4 million loans FHA has insured since fiscal 2009 have credit scores of 680 or higher, Chappelle says. In addition, last year Congress restored the maximum amount FHA could insure to $729,750.

The agency also reduced its risk by eliminating in 2008 the disastrous seller-funded down payment programs that contributed to massive delinquencies and an estimated $14 billion in losses.

Still, FHA uses outmoded economic models that underestimate its risks to borrowers and taxpayers, plenty of critics say. A bailout may still be needed in coming years, depending on the economy, they say.

Many FHA loans are unsustainable because the agency insured so many loans with very low downpayments during the recession, when house prices were falling, says Andrew Caplin, an economics professor at New York University.

As a result, the success or failure of those borrowers is hard to track given that FHA allows borrowers with high loan-to-value ratios to refinance without requiring a new appraisal. Though no new underwriting is required for a streamlined refinancing, FHA does not track the performance of such borrowers across loans, he says.

"It's very, very shocking that in the modern version of finance, the agent that doesn't have to be concerned with the borrower's ability to pay is the government," says Caplin, who has urged FHA to track whether such loans support sustainable homeownership over time.

Caplin estimates that 30% of FHA borrowers will be seriously delinquent in the next five years largely because the borrowers are underwater and owe more on their mortgage than their home is worth. In addition, there is no alternative private financing available to such borrowers since the government remains the primary insurer of 90% of all mortgages.

Ed Pinto, a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, says FHA is manipulating its capital position by charging higher up-front premiums. It also is increasing its risk by financing the premiums as part of each borrower's loan balance, he says.

"If FHA were a private insurance company, they would be required to bring that income in slowly over the expected life of the loan," Pinto says. "Instead, they're bringing it all into income and spending it."