As big banks announce seven-figure cost-cutting plans, Steve Zeman frets over wasting $2,300 on a software upgrade.

Zeman, president of the $88 million-asset Union State Bank of West Salem in Wisconsin, recalls spending the money to comply with a portion of the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act that was changed soon after the upgrade was made.

For Zeman, it was another instance of “crushing” compliance costs for tiny banks.

“It’s very hard to stay current with all of the interpretations of the various regulations and to cover the costs of the technology necessary to be in compliance,” Zeman said. “This is just one example of the resources wasted that could have gone into more customer service and more investment in our community.”

Union’s wasted expenditure highlights how community banks are monitoring every single expense to maximize profitability. They seem to be doing a good job: Smaller institutions are producing solid returns despite competition, regulation and a flat yield curve, among other things.

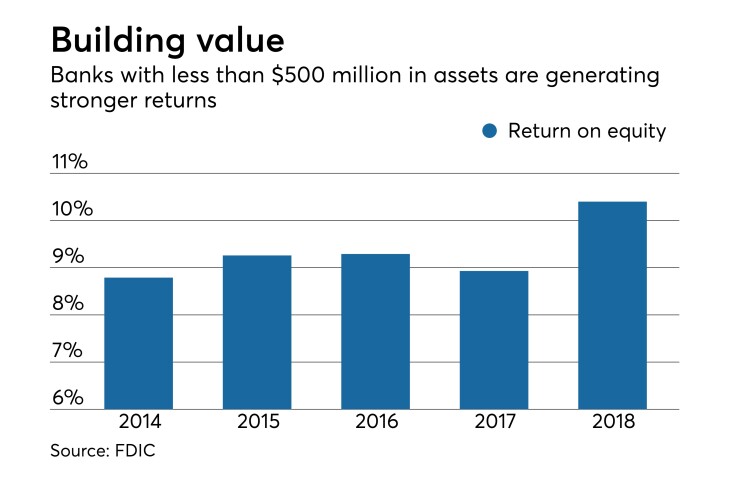

The number of banks with less than $500 million in assets fell by 22% between 2014 and 2018, according to data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

But those banks have also become more profitable, with average 2018 earnings rising by 35% from 2014, to $2.2 million. Return on assets rose from 0.98% to 1.21% over that period, while return on equity topped 10% for the first time since 2006.

Lower taxes have helped, said Michael Jamesson, a principal at Jamesson Associates, a community bank consulting firm in Scottsville, N.Y. At the same time, smaller banks, mostly those in more rural areas, have been able to keep deposit prices in check. Finally, asset quality remains very good, which is keeping loan-loss provisions at modest levels.

All of those metrics have been enough to convince many community banks to stay independent despite numerous internal and external challenges.

“I have learned over the years that complaining … doesn’t help much,” said Mike Fleming, president and CEO of the $101 million-asset Litchfield National Bank in Illinois. “It is far better for me to spend my energy on all the positives.”

Litchfield can succeed as long as it keeps on eye on credit quality and operating expenses, which Fleming views as the key to producing reasonable returns for investors.

Challenges are driving a large number of community banks to build scale, especially those in competitive metropolitan areas.

While the $479 million-asset Freedom Bank of Virginia must get bigger to improve profitability metrics and the overall value of its stock, being larger also has its disadvantages, said President and CEO Joe Thomas.

“As banks get larger … they cannot provide an entrepreneurial environment for employees, unique experiences for clients or engagement with local communities in a way that we can,” Thomas said.

The goal for Freedom is to increase its tangible book value by 10% annually. It doesn’t plan to pursue acquisitions to get bigger, since it has a relatively low valuation and concerns about buying banks with large concentrations of commercial real estate, Thomas said.

Scale has become more important for banks that eventually decide to be sold. Buyers are showing more of an interest acquiring bigger banks given the time, resources and risk associated with mergers.

The $396 million asset Andover Bank in Ohio is focused on keeping borrowers and depositors, while offering attractive checking and savings products to bring in new customers, said President and CEO Stephen Varckette.

The operating environment is difficult for small banks because of a flat yield curve, Varckette said. Andover had a 10.13% return on equity in 2018.

“We’re anticipating pressure on our net interest margin throughout the year,” Varckette said.

Union State, which generated a 4.56% return on equity last year, wants to stay independent, though Zeman conceded that it won’t be easy. In addition to regulation, he is frustrated at the amount of competition that comes from credit unions in his market.

“We’re able to compete with customer service and community involvement, but competing on interest rates for loans and deposits is nearly impossible,” Zeman said.

Litchfield plans to go it alone, though Fleming said the bank would entertain an offer if it was mutually beneficial, adding that he has noticed more cooperation among community bankers than he’s ever seen in 30-year career.

Litchfield produced an 8.81% return on equity last year.

“I think there’s a real belief among us community bankers that banding together will help us all succeed,” Fleming said. “It’s all about having the right attitude.”