Ah, simplicity.

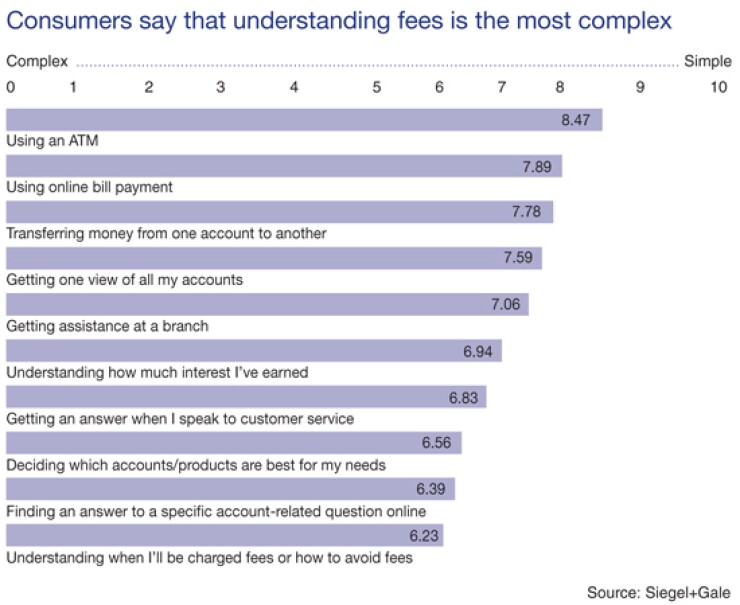

If only it weren't so complicated. Customers say that disclosures from banks are confusing. They aren't clear about when fees will be incurred or how to avoid them. Offered an array of checking accounts, they struggle to figure out which one suits them best. And finding an answer online, or getting one on the phone, isn't as easy as it should be.

All of this makes people suspicious, says Brian Rafferty, global director of customer insights for the brand strategy firm Siegel+Gale. "In a sense, it's like, 'They're trying to rip me off and that's why I can't understand what they're saying to me.'"

Rafferty says he doesn't believe banks intend to be so perplexing, but the fact that their customers think soa perception evident in his firm's annual simplicity study-cannot be ignored.

"If you agree there's been a kind of crisis of trust in the general public with the financial services industry, to rebuild trust is not to do a large ad campaign saying, 'You can trust us.' It's to really demonstrate it through these daily interactions with people," Rafferty says.

Though complaints about complexity are long-standing ones for the industry, addressing them is taking on new urgency. Customers are revolting over new fees, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is now watching to make sure banks speak to consumers in language they can understand, and startups like Simple and Movenbank are getting a lot of media buzz by promising to be more transparent and easier for customers to interact with.

"I think there is an industry imperative to simplify," says Michael Beird, the director of banking services at J.D. Power and Associates. "A lot of banks are so afraid of being in trouble from a regulatory perspective that they hide behind their disclosures, but I think there is a desire to step away from the legalese," he says.

JPMorgan Chase is a case in point. The company announced in December that it was simplifying disclosures, starting with its Total Checking account, which has 8 million customers. The move was part of what Ryan McInerney, CEO of Chase's consumer bank, describes as a broader mission to examine interactions through the eyes of customers to make sure the bank is being clear and simple.

Chase held focus groups and one-on-one customer interviews to get feedback on its existing disclosures and thoughts on how to reword them.

McInerney says the bank started with the model disclosure form proposed by Pew Charitable Trusts, a group that has been advocating for more consumer-friendly communications from banks, and then applied tweaks based on Chase's own research. The process took several months.

The new three-page summary of disclosuresculled from a document that McInerney says is significantly larger-details all of the instances that would trigger fees and ditches the typical bankerspeak.

"One of the most complicated things for customers is this arcane banking topic called posting order," McInerney says. The new disclosures contain phrases like "how deposits and withdrawals work"- which is the language customers used after Chase explained to them what it meant by posting order.

"What we've found is, you really do have to talk to customers and just describe to them what you are trying to convey, and give them a piece of paper and a pen and say, 'How would you talk to your family about that?'" McInerney says. "That's the approach we took."

Chase plans to carry through in the same way with other types of disclosures and customer letters. When unveiling the new disclosures for its Total Checking account, Chase also eliminated several fees, including a $25 charge that applied to anyone who closed an account within 90 days of opening it.

Seigel+Gale surveyed more than 6,000 consumers in seven countries for its second annual Global Brand Simplicity Study. It fielded the study in early fall, before Chase announced any changes.

Nonetheless, the study singles out Chase for making critical improvements in simplicity, such as enabling customers to deposit checks via smartphones.

Banks in general performed better, too. The simplicity score for the industry rose 11 percent from the previous year.

But there's still a long way to go. Of the 25 industries included in the study, which rated Internet retail the best in simplicity and health insurance the worst, retail banking ranked 15th, squarely in the bottom half. Chase scored the highest among banks, but it was outranked by 99 companies in other industries.

Siegel+Gale defines simplicity as ease of understanding, transparency, caring, innovation and useful communications. The firm, whose work for the Internal Revenue Service led to the development of the 1040EZ form, argues that complex companies could generate more loyaltyand profitif they were willing to be more transparent and create simpler experiences for customers.

The study even tries to quantify some of the potential for simplicity to add to the bottom line.

Among U.S. consumers, 8 percent say they would be willing to pay more for simpler retail banking. On average they would pay an extra 2.4 percent. Based on industry revenue, Seigel+Gale calculates the payoffwhat it calls the simplicity premium-to be $1.4 billion.

As Rafferty concedes, "Lots of the ways in which you can simplify the interactions with financial services aren't things that you would actually be able to charge for."

He also says that for consumers, "It's much easier to say, 'I'm going to pay them,' then it is to actually pay."

Still, the concept of simplicity clearly resonates with consumers. "Banking in America has gone too long on a revenue model driven by customer confusion," Joshua Reich, the CEO of Simple, said in one of the recent articles about his firm, which boasts that it will charge no fees.

But Ron Shevlin, a senior analyst at Aite Group, is skeptical about whether even startups can transcend complexity in this industry.

"BankSimple and Movenbank, God love 'em, have their hearts in the right place, but they have achieved nothing to date in the way of real business results. Nice aspirations, but let's see how 'simple' they are when they scale to a million customers."

Given the patchwork way in which financial services companies have been formed, it's no surprise that customers of established banks are confused.

"It's not uncommon for an institution, particularly one that's evolved through merger, for example, to have 15 or 20 different checking account offerings," says Steven Reider, president of Bancography, a Birmingham, Ala., consulting firm.

"So think about the person in the call center trying to answer a question about a certain feature or why you got this charge. You say, 'I have the super duper premium checking account,' and they have to think, 'Does that come with a waiver of ATM fees? And is that $6 or $8?'"

Reider says customers want simplicitybut without any added expense. "I think there are very, very few things that customers are willing to pay a premium for in banking. We have created an expectation of nearly free everything."

Even so, simplification might benefit banks by keeping customers from even wondering if another bank might be easier to deal with.

J.D. Power, in its annual study of customer satisfaction in retail banking, asks people about how well they understand their bank fees. Those who profess to have greater understanding generally express higher satisfaction with their bank. Those with less understanding are more likely to say they plan to switch banks. "There's a retention and attrition factor that plays in," J.D. Power's Beird says. "I think there is a monetary incentive to banks to simplify and to help customers understand."

Beird says he often gets asked how banks can improve customer satisfaction. He frequently recommends training staff to talk about specific fees at the account opening, instead of limiting the discussion to happy topics like rewards, as they often do.

"Isn't it easier to hand the customer a 40-page brochure and say, 'Read this sometime and call me if you have any questions,' as opposed to, say, 'Let me explain to you in plain English what you're going to be charged'?"

His suggestion is to boil down all the complex legal disclosures associated with checking accounts to one simple page that specifies when fees are triggered. "If your balance falls below this, we charge you that. If you write this many checks, we charge you this. If you go to somebody else's ATM, we charge you this," Beird says. "That's simplification in my view."

Bonnie McGeer is the managing editor of American Banker Magazine