WASHINGTON — Banks have long urged the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. to modernize brokered deposit rules. But the focus is shifting to whether policymakers should repeal those rules altogether.

Banks with damaged capital are currently restricted from accepting brokered deposits. The aim is to prevent an unhealthy institution from growing too fast, potentially leaving the FDIC with a costly failure.

The FDIC is poised to revise the definition of brokered deposits to ease the restrictions. Yet a pending bill to replace those restrictions with explicit asset growth limits has spurred a new debate. Supporters of the idea say it better addresses the problem of overheated growth, but other say throwing out brokered deposit limits is a mistake.

“Rapid asset growth is a problem, every analyst would agree,” said Paul T. Clark, partner at Seward & Kissel. “Most people agree that the current brokered deposit standards are not designed for and laser-focused on that problem.”

But skeptics worry that the legislation proposed by Sen. Jerry Moran, R-Kan., could invite undercapitalized banks to rely on "hot money" to stay afloat.

“At the end of the day, brokered deposits are all about hot money, which destabilizes financial institutions,” said Dennis Kelleher, president and CEO of Better Markets.

Banks and their advocates have insisted

The difference between then and now is that the FDIC appears to agree. Under a pending proposal released in December, the FDIC said it was considering clarifying the definition of brokered deposits by narrowing how it defines a "deposit broker."

“The current framework for brokered deposits is, frankly, completely antiquated, given the nature of the banking system today and comparing it to what it was 40 years ago when we promulgated these regulations,” FDIC Chair Jelena McWilliams said in an interview. “If we can modernize the brokered deposit system, I think it will give the ability to banks to do more with brokered deposits without increasing the risk.”

The bill would task the FDIC with creating

“This legislation is a pragmatic modernization of the regulatory environment that focuses on the issue the outdated regulations were intended to resolve," Moran said in an emailed statement. "This modernization simply directs the law's emphasis where it belongs, direct oversight over asset growth and asset quality, while facilitating the relationships that allow community banks to thrive.”

McWilliams has also endorsed the idea behind Moran's bill: focusing directly on asset growth, instead of barring a struggling bank from using brokered deposits.

“One option to consider is replacing Section 29 of the FDI Act altogether with a simple restriction on asset growth for banks that are in trouble,” McWilliams said in a speech last year. “This would be a far easier regime for the FDIC to administer, would at the very least limit the size of the FDIC's potential exposure, and would more directly address the key goal of preventing troubled banks from using insured deposits to try to grow out of their problems.”

Some former regulators say homing in on brokered deposits can make for an imperfect approach to restricting growth. The source of an institution's funds, they say, is not as relevant as how the bank deploys those funds.

“It’s less important where the money comes from than the characteristics of the money,” said John Bovenzi, a partner at Oliver Wyman and former senior FDIC official. “The money can come from brokers, or it can come from the internet, or from a branch. Some of each type of deposit have good characteristics and some have bad ones depending upon the situation.”

But the FDIC has historically expressed concern about banks with high concentrations of brokered deposits. In the 2008-9 mortgage crisis, several of the costliest bank failures involved institutions with ample brokered funds relative to total deposits. Those institutions had grown rapidly in the lead-up to the real estate crash. Such failures were costly for the FDIC; brokered deposits are covered by the agency's insurance guarantee, but they deplete a failed bank's franchise value to prospective acquirers.

Brokered deposits are “the hottest and most destabilizing of money [that] exists for the sole purpose of chasing the highest returns with no more thought than a keystroke,” Kelleher said.

Section 29, added to the Federal Deposit Insurance Act in 1989

Banks have

“The only limitation on brokered deposits applies to ... the banks that are the weakest and most vulnerable and, by the way, the biggest threat to the DIF,” Kelleher said.

The trouble, bankers say, is that banks’ capital levels often take a hit in an economic downturn. A previously strong bank may suddenly be slapped with restrictions on how it can seek funds at the precise moment it most needs flexibility. In a

“Brokered deposits aren’t the cause of a bank growing too fast and taking on too much risk,” said John Tyson, chief financial officer of the $175 million-asset Altamaha Bank in Vidalia, Ga. “Yes, it facilitates it and makes it easier for the bank to do that, but the real issue is loan growth, and the risk they take in the portfolio relative to their capital level.”

Some industry advocates say expanding access to brokered deposits for well-capitalized banks is less an act of deregulation than acknowledging market reality. While regulators often stress that brokered deposits are volatile and can leave a bank suddenly in favor of higher returns elsewhere, others point to the broader brokered deposit ecosystem as being stable.

“My argument for 30 years has been that we have a national market. If you go out to any broker and tell them you need to replace [certificates of deposit] with other CDs, you can,” Clark said. “This embedded notion that brokered deposits can’t be replaced falls apart, because we have a marketplace with national pricing.”

He added that community banks in particular need more flexibility.

“Community banks need access to the national deposit market,” Clark said. “As the number of banks has shrunk and consolidated, deposit funding has become a lot more competitive, and small banks need to be able to reach outside their markets to attract funding.”

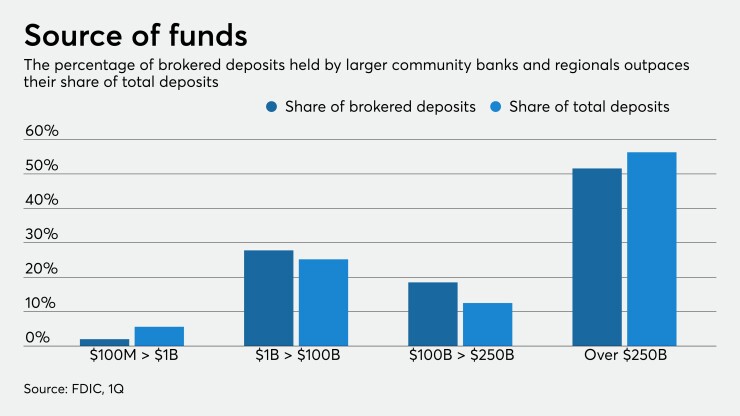

The vast majority of brokered deposits as currently defined rest not in the smallest institutions, but in the largest. According to the most recent data from the FDIC, more than 50% of brokered deposits reside in just 13 banks with assets greater than $250 billion. Banks with assets below $10 billion hold less than 10%.

Still, the data points to evidence of banks across several asset classes relying significantly on brokered deposits. Banks with under $250 billion of assets hold about 44% of all deposits, but they have 48% of all brokered deposits. Meanwhile, among banks with $1 billion to $100 billion of assets, brokered deposits make up 8.4% of their total deposits — versus 11.3% for banks with assets of $100 billion to $250 billion and 7% for banks with assets above $250 billion.

McWilliams's 2019 speech, at the Brookings Institution, was intended to preview the FDIC's proposed rulemaking. But she also questioned the need for Section 29 in the first place.

“The statute mandates that the FDIC use a blunt tool to address an important policy problem,” she said, adding, "There might be better ways to accomplish the worthwhile public policy goal Congress intended to address" in 1989.

A call to shift focus away from defining brokered deposits is a departure for the FDIC.

In 2011, the FDIC conducted a study of brokered deposits and their role in exacerbating the 2008 crisis. "The FDIC has concluded that the brokered deposit statute continues to serve an essential function and recommends that Congress not amend or repeal it," the study said.

“During the most recent crisis, the statute has, in large measure, prevented failing banks from increasing their brokered deposits, and, therefore, from taking on greater risk in an effort to grow out of trouble and prevented greater FDIC losses when banks fail,” the study’s authors wrote.

The FDIC affirmed the core of those findings as recently as 2018, when the agency’s researchers found a "statistically significant" correlation between the amount of brokered deposits a bank has and the likelihood it would be hit with an enforcement action within four quarters.

However, McWilliams's leadership has brought a new perspective to the FDIC after she took over from former Chairman Martin Gruenberg, an Obama appointee who still sits on the board.

Officials at the agency now believe the FDIC’s brokered deposits regime encapsulates too many different kinds of deposit arrangements, many of which don’t appear to have the same characteristics as those that contributed to large losses in past crises.

Six months after McWilliams’s Brookings speech, Moran submitted a bill to Congress that would remove the phrase “brokered deposits” from Section 29 and replace it with “asset growth restrictions.”

In the interview, McWilliams said an asset-growth-focused framework would strengthen regulators’ ability to limit rapid growth, freeing examiners to look beyond the dangers of one type of funding — brokered deposits — and scrutinize other types of growth-related risks.

“That cap that Congress put on the growth of brokered deposits at a bank that may be undercapitalized is an artificial barrier, frankly,” McWilliams said, adding later: “We do have some tools to limit the growth of the assets of the balance sheet of the bank — if the bank is in critical condition, etc. What we’re trying to accomplish with our support of the cap on asset growth is take away the inflexibility and rigidity around brokered deposits."

She said Congress shouldn't think that "just because they limit the growth of brokered deposits, we’re done.”

Moran's bill, however, could face a difficult path to passage, particularly in the Democratic-controlled House. But the American Bankers Association is throwing its weight behind the proposal.

“Today, a deposit classified as brokered is labeled as such due to an outdated legal construct, rather than any enhanced risk characteristics,” James Ballentine, the ABA's executive vice president of congressional relations, wrote in a June 16 letter to Moran. “The result is that even well-capitalized banks are strongly discouraged from holding an otherwise stable source of funding.”

Alison Touhey, vice president of bank funding policy at the ABA, said the current rules predate the internet, so they treat deposits gathered through online platforms and fintech partnerships as brokered regardless of the risks.

"No one is arguing that the risks the rules were originally intended to control for have disappeared, but clearly the way we should control for them must adapt to this new reality," she said. "Banks are meeting their existing and new customers where they are — online, on mobile devices and through affiliate relationships."

Moran’s bill is just five pages long and would defer largely to the FDIC in building the framework. In consultation with other regulators, the agency would “promulgate regulations imposing a restriction on average total asset growth for insured depository institutions that are less than well capitalized.”

Several observers say even though eliminating the brokered deposit definition would be a significant step, the FDIC already has sufficient authority to regulate asset growth. In fact, the agency issued a rule in the 1990s, which it later rescinded, preventing banks from increasing their assets more than 7.5% during a given three-month period without notifying the FDIC.

“This bill strikes an existing rule and grants a bunch of authority that I suspect the FDIC already has,” said Aaron Klein, policy director of the Center on Regulation and Markets at the Brookings Institution.

Even Clark, the Seward & Kissel partner, agreed that "new legislation isn’t actually necessary" to give the FDIC authority to limit asset growth.

Klein said that in general, he understood the need to modernize brokered deposit rules. “Over time, technology and definitions have changed, so some of the things that are captured under the brokered deposit rule today aren’t really hot money,” he said.

But “that can be done by updating the definition of brokered deposits, not by gutting the law or eliminating the concept,” Klein added.

In an

“Bank regulators have long had the implicit authority to limit asset growth at troubled institutions, and have done so on individual cases. This has not solved the issue of the correlation between brokered deposits and bank failures,” Kovacevich wrote.