If time is money, then bank M&A has gotten more expensive.

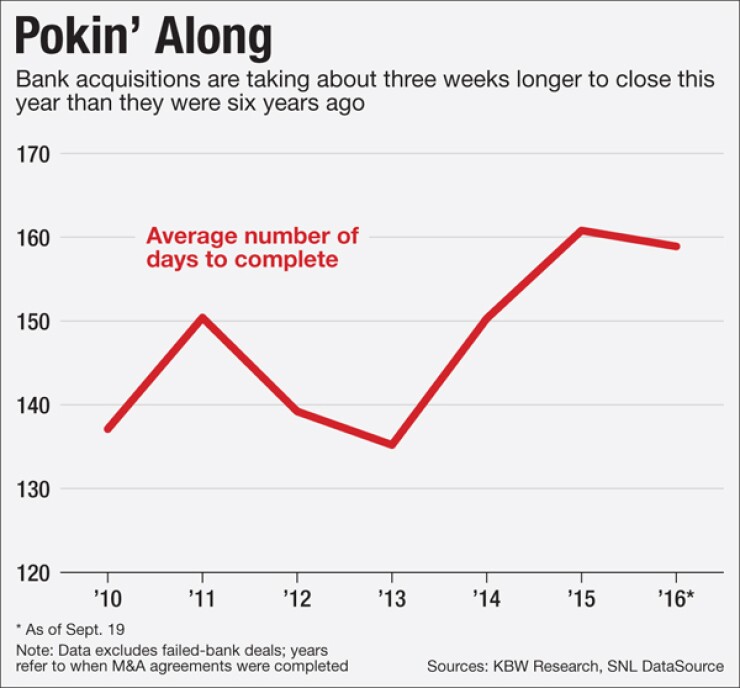

The average deal takes three weeks longer to complete than it did six years ago because of various regulatory and business reasons, lengthening the amount of time that the parties can get cold feet or impatient customers can walk. But there are precautions buyers and sellers can take to smooth the process and minimize those risks.

"We think there is a real need, from the public announcement to closing, to make that as short of a time as possible," said Bob Wray, the president and chief executive of Capital Corp., a firm that provides consulting and investment banking services. "The greater the risk the longer it gets drug out."

Through mid-September, roughly 159 days had lapsed, on average, between a deal's announcement and its completion this year, up from about 137 days in 2010, according to data from Keefe, Bruyette & Woods. There are multiple reasons, all tied to regulatory and industry changes, experts said.

There are multiple reasons, all tied to changing times, experts said.

For one, regulators are taking a closer look at deals, including more thorough reviews of buyers' operations than they conducted before the financial crisis, said Tom Rudkin, a principal at DD&F Consulting Group.

Before the crisis sellers generally drew more scrutiny because regulators wanted to ensure any deals would not create problems for the buyers, Rudkin said. But now both sides are being put under the magnifying glass, he said.

"Regulators are being cautious about approving these deals quickly," Rudkin said. "They don't want to create another problem by putting together two mediocre banks, so it has added a little more time."

Acquirers are also taking deeper dives in examining the credit quality of sellers' loan portfolios and their compliance track records, said Tony Plath, a finance professor at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. Banks conduct an initial level of due diligence before a deal is made and announced, and they generally keep reviewing the seller's loan portfolio before the transaction closes, he said.

Ensuring that sellers have "their ducks lined up" regarding compliance — whether with Dodd-Frank rules against unfair, deceptive, or abusive acts and practices; with new mortgage disclosure rules; or with other matters — adds time to deal closures, Plath said.

"The biggest issue with any bank combination is credit," Plath said. "You can't be wrong on credit because it will diminish the value of the deal."

Though heightened regulatory scrutiny is adding time to deals, it may not always show up in formal processing times. The median number of days for the Federal Reserve to process applications has remained fairly steady over the last five years, ranging from 40 to 42, according to its recently released semiannual report on banking application activity.

But there are other hands in the process, experts said. Multiple banking regulators and even the Securities and Exchange Commission can be involved in approving deals.

"It's not a matter of who is the fastest but who is the slowest," said Jonathan Hightower, a partner at Bryan Cave.

Moreover, many institutions like systems conversions to coincide with deal closings. When working with outside core-systems providers, buyers usually need to set a conversion date well in advance and sometimes have to secure that date by paying a nonrefundable deposit, Hightower said. However, more banks are being conservative in planning their conversion dates and are giving themselves plenty of time in case there is a delay in regulatory approval.

"That as much as anything is being a driver of this longer time between signing and closing," Hightower said. "They have the perception that regulatory approval may be delayed significantly, so they don't want to set that date too quickly. Otherwise they may have to move it, and that could delay things further and could cost them some money."

There are several steps banks can take to ensure deals go smoothly, industry experts said. Best practices should generally start with good communication with regulators.

Randy Shannon, the chairman of Citizens Bank in Amsterdam, Mo., makes sure he has a good relationship with his primary regulators by calling them at least once a year and reaching out anytime he thinks he is close to finalizing a deal. He said he has heard from regulators about how much they appreciate the transparency. So far, he has been involved in three deals in the last few years and is currently pursuing another.

"You should have a track record of communicating with them on a periodic basis," Shannon said. "We try to shape their expectations so when we drop our application for an acquisition it's not a surprise to them. Many banks don't talk to their regulators because they see it as an adversarial relationship."

Echoing that advice, Wray said his clients are spending more time working with regulators on the pre-application process than before the financial crisis. Privately held banks that decide to go through the prefiling process generally do it before publicly announcing a deal. Public companies may decide not to prefile since they have to announce their deals once an agreement is signed.

Wray encourages his clients to walk their regulators through a transaction to find out what they are looking for. All of this could add anywhere from a couple of weeks to a couple of months to getting a deal done, but it can also improve the chances of approval.

"We believe it is really important for the regulators to feel included," Wray said. "They express their gratitude about getting a heads-up."

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and the Fed all declined to comment for this story.

Potential acquirers need to make sure their own regulatory and compliance affairs are in order before looking to buy another institution, said Christopher McGratty, an analyst at KBW. That advice is reflected in

Institutions with less than satisfactory ratings in safety and soundness, community reinvestment or consumer compliance, or those that are under a formal enforcement action, will find it more difficult to win regulatory approval for a deal. Another impediment could be the funding of an acquisition using debt that matures in less than three years, according to the Fed document.

"You have to make sure your own house is in check before looking at someone else," McGratty said. "Anytime you deal with the approval process, you need to make sure you are in good standing."

Heartland Financial USA in Dubuque, Iowa, has completed 21 acquisitions since 1980 — with about half of those having occurred in the last five years. For the $8.3 billion-asset company's last six deals, it has taken on average 123 days to close, said Chairman and CEO Lynn Fuller.

Heartland takes advantage of regulators' expedited reviews permitted for qualified, healthy buyers, and its rapport with regulators and consistent strong performance have also smoothed the way, Fuller said.

"All of those acquisitions have worked out without any hitches, so that matters," he said. "We don't have any issues with regulators, and we keep them well informed. Our performance is also good. I think to a great extent that's why we have never had any pushback on our transactions."