During the Obama administration, U.S. banks were often at loggerheads with the federal government over unwanted automated calls to consumers.

But in the early days of Donald Trump’s presidency the industry has good reason to believe that some of the existing restrictions will be softened. Such changes could be a source of substantial savings for banks and credit unions, particularly in the realm of consumer debt collection.

The rules governing robo-calls to mobile phones —

Analysts at Compass Point Research & Trading said in a note Monday that they expect the FCC to pursue a “broad deregulatory agenda” during Trump’s presidency, including a softening of the robo-calling rules.

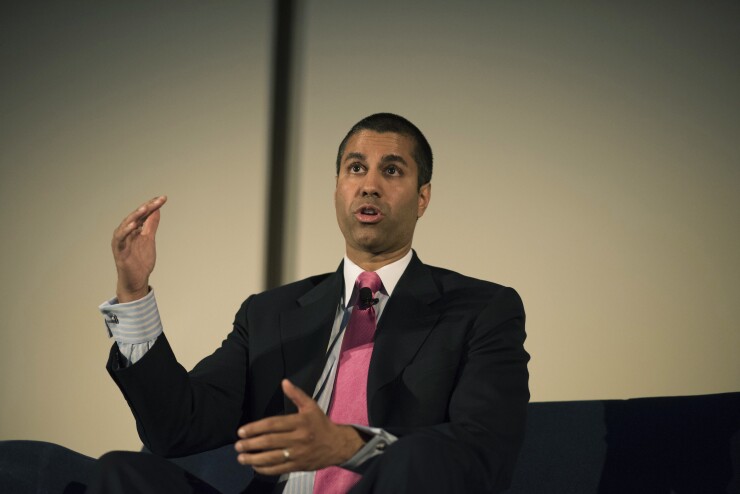

Newly installed FCC Chairman Ajit Pai

Pai, a Republican who joined the commission in 2012, voted against the 2015 robo-calling rules. Those restrictions, which passed 3-2 on a party-line vote, mostly rejected entreaties made by banks and other companies.

For example, the rules held that companies can be held liable even if they call a phone number without realizing it has been reassigned to a new customer. The Telephone Consumer Protection Act establishes strict liability for callers — $500 for each unsolicited call to a mobile phone, or $1,500 for intentional violations.

“This will certainly help trial lawyers update their business model for the digital age,” Pai said during a June 2015 hearing.

Those comments echoed arguments frequently made by banks, which have paid more than $200 million in recent years to settle robo-calling lawsuits.

Shortly after being appointed by President Trump as the FCC’s new chairman, Pai

The FCC currently has only three members, including Republican Michael O’Rielly, who is also a critic of the agency’s current robo-calling rules.

Trade groups representing banks and credit unions are viewing the recent change in leadership at the FCC as an opportunity. In a letter to Pai last week, the National Association of Federally-Insured Credit Unions asked the agency to reconsider its rules, which it said do not reflect the realities of life in 2017.

“Cellphones have largely replaced landlines, and consumers expect to receive the same service from their credit union regardless of the type of phone line they have listed,” the trade group’s president, Dan Berger, wrote.

Kate Larson, a vice president at the Consumer Bankers Association, said in an interview Tuesday that aggressive trial lawyers and U.S. consumers’ shift away from landlines have led to a surge in lawsuits.

“Litigation risk is deterring banks from communicating with their customers,” she said.

For banks, looser rules on robo-calls could also yield operational savings, in addition to lower legal costs. During a recent conference call with analysts, Discover Financial Services CEO David Nelms said that the FCC’s rules have forced the firm to collect debt in less efficient ways than it would otherwise.

“In fact, we’ve had to spend a lot of money and go to a lot of trouble,” Nelms said.

Consumer advocates are far less enamored of the prospect of looser rules.

“The question really is how much the FCC cares about protecting consumers,” said Margot Saunders, an attorney at the National Consumer Law Center.