-

BNY Mellon is facing a $900 million tax bill after a U.S. judge rejected its attempt to claim hundreds of millions of dollars in foreign tax credits.

February 12 -

BB&T announced Thursday that it earned $210 million in the first quarter, compared with $431 million a year earlier, as it took a $281 million charge related to a tax dispute with the Internal Revenue Service.

April 18

One tax loophole may have closed permanently, but banks can rest easy there will be more where that one came from.

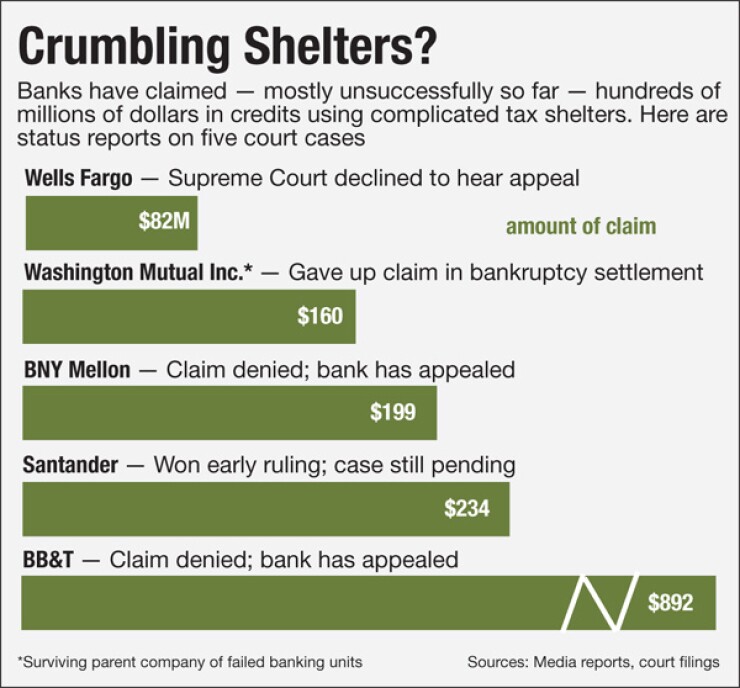

The U.S. Supreme Court dealt a blow to a tax shelter on June 9 from which Wells Fargo (WFC) was trying to claim an $82 million tax refund. The high court

Wells and three other institutions BB&T (BBT), Bank of New York Mellon (BK) and Banco Santander (SAN) continue to pursue related litigation in other courts. The tax credits they claimed range from roughly $200 million to $900 million.

All these cases involve the legal question of economic substance, a doctrine of law that says a transaction must have an economic benefit other than the reduction of a tax liability. While the Supreme Court rejected one Wells tax shelter, saying it lacked economic substance, the issue is far from dead, says Lee Sheppard, a tax attorney and contributing editor to Tax Analysts' Tax Notes.

The courts are being asked "big questions of law," she says.

Banks will be able to take legal principlesboth from the Supreme Court's rejection and from the separate, ongoing litigationfrom which they can develop new tax strategies, Sheppard says.

"They may figure out some other way to do tax shelters, but not this kind" that the Supreme Court rejected this month, she says. "When all this comes out in the wash, maybe we can get a legal principle to help the creation of new shelters."

In the cases that are still pending, Wells and the other banks are attempting to reclaim taxes through their use of structured trust advantaged repackaged securities (STARS). The Internal Revenue Service had rejected the use of the STARS vehicle, saying banks were taking improper deductions. Wells is attempting to reclaim $148 million in taxes and penalties through its use of STARS.

The STARS transactions involved extraordinarily complicated agreements between each of the banks and the British bank Barclays before the financial crisis. Barclays sought to take advantage of U.K. tax laws to offer lower-cost funding to U.S. institutions. The banks said it counted as foreign income deserving of foreign tax credits against U.K. taxes that were paid; the IRS said it should have been characterized as U.S. income.

Examined more closely, the STARS deals were "surpassingly complex and unintuitive; the sort of thing that would have emerged if Rube Goldberg had been a tax accountant," U.S. District Court Judge George O'Toole wrote in an Oct. 17 order in Santander's case.

"The government might be forgiven for suspecting that the designers of anything this complex must be up to no good," O'Toole wrote.

Even if banks and their consultants are able to devise new tax shelters based on STARS, the deals are most likely to be beneficial only to large banks, Sheppard says.

"If you're a big giant bank and you're too big to fail and you've got your fingers in every pie, you can bury this in your business," she says. "But if you are a little bank and you don't have any foreign operations, it sticks out" as more noticeable to regulators and tax officials.

The rejected STARS deals have proven to be costly to the banks that used them. In February 2013, a U.S. Tax Court judge

The $181 billion-asset BB&T, in Winston-Salem, N.C.,

BB&T, Santander and Wells declined to comment. BNY Mellon did not respond to requests for comment.

Banks can take some hope from the case involving Banco Santander, the Spanish company that owns $75 billion-asset Santander Bank, both Bassin and Sheppard said. In that case, Judge O'Toole ruled that Santander's use of STARS met the requirements of the economic substance doctrine, meaning that Santander had a reasonable expectation of deriving a profit from the deal.

"The existence or not of a reasonable prospect of profit is critical in determining whether the transaction had objective economic substance for purposes of assessing whether it was a 'sham' or not," O'Toole wrote in the Oct. 17 opinion, which granted partial summary judgment to Santander.

Banks and their attorneys are almost certain to seize O'Toole's legal reasoning to make their case in future litigation, Sheppard says.

"There is a lot of money at stake, and banks are always looking for deals," she says.