Facing pressure from investors and regulators, banks have added more women to their boards in recent years. But are those moves leading to safer, sounder institutions?

A new study by Moody’s Investors Service suggests a slight correlation between greater gender diversity on bank boards and higher credit ratings. But the study runs into a problem that often plagues attempts to measure environmental, social and governance metrics: a lack of consistent data.

Because its sample size was so small, Moody’s did not find a conclusive link between gender diversity at the board level and a higher credit rating. Sadia Nabi, a senior analyst at the firm, expressed frustration with the limited amount of information that banks make available about diversity in their ranks.

“Even though a majority of the banks talk about it, there is very limited detail on what numbers there are or what plans they have for the future,” Nabi said.

The composition of bank boards has faced scrutiny in recent years, and the social upheaval of 2020 only intensified that pressure. Board diversity is critical because directors exercise influence over a bank’s culture and strategic direction, say investors and regulators who have been leading the charge.

The Nasdaq stock exchange

Moody’s evaluated 72 North American banks, 20 of which had a baseline credit assessment of a2 or higher. At the more highly rated banks, 28% of the directors were women, compared with 26% of board members at lower-rated banks. A baseline credit assessment essentially refers to the probability that a company will default on its debt obligations.

The ratings agency said that it intends to use this study to establish a baseline from which it can measure the impact of what it expects will be a continuing effort by banks to diversify their leadership ranks.

Earlier studies by Moody’s have found a stronger correlation between gender diversity and a higher credit rating.

For example, in a Moody’s study of European companies that was published in March 2020, 30% of the directors at highly rated companies were women, while women accounted for just 16% of board seats at companies in the study’s lowest ratings tier.

But some observers question the premise that gender diversity in the boardroom is linked to financial performance.

“There is no clear evidence that diversity in and of itself produces better financial results,” said David Baris, president of the American Association of Bank Directors. “That doesn’t mean that bank boards should not consider diversity, it doesn’t mean there may not be other benefits, but just by the studies themselves, it’s inconclusive in our view.”

Currently, the trade group urges member banks to consider criteria such as individuals' experience, reputation, intelligence and connection to local communities, and it discourages them from looking at factors like gender, race and sexual orientation. It has yet to decide whether it will change or update its guidance to member banks based on

For many smaller banks, the search for a new director may well start and end with the current directors’ immediate social and professional circles. For that reason, the American Association of Bank Directors has long advised its member banks to look to their broader communities in an effort to find potential candidates, Baris said.

Recent

“I happen to think that if a board follows our advice and the advice of the Federal Reserve, it will likely produce a board that is diverse in different ways,” he said.

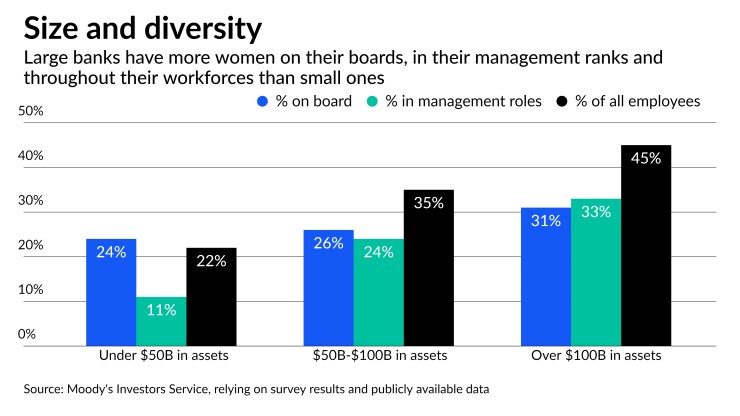

The Moody’s study found that large banks tend to have more gender diversity on their boards than smaller banks, likely in part because bigger companies have more resources to pursue diversity and inclusion initiatives.

At the five largest U.S. global investment banks, women held 40% of board seats, the study found. At regional banks, 24% of the directors were women. Big banks were also more likely to have more female representation in their executive ranks and throughout their workforces than smaller banks. Moody’s noted that many of the largest U.S. banks have operations in Europe, where they need to comply with more stringent rules on gender diversity.

The study’s findings also suggest that banks could do a better job of supporting women’s career advancement. Women made up 56% of all employees at the banks Moody’s examined, but just 38% of management executives and 27% of board members. Another

One possible explanation may be that women are concentrated in non-revenue-producing lines of business, such as legal and accounting, while employees in revenue-producing roles are more likely to get promoted to leadership positions.

“The talent pool is there, banks are hiring, everybody is hiring,” Nabi said. “Then the progression kind of stops, and the key question becomes, what’s going on here?”