WASHINGTON — The Obama administration did not make the same mistake twice.

A week after being hammered for offering a bank assistance plan that lacked details, the administration unveiled a sweeping and detailed plan Wednesday to prevent millions of foreclosures. It includes just about every suggested solution: loan guarantees, greater incentives to lenders and servicers, and expanded use of the government-sponsored enterprises.

It even included a stick to go with the carrots: a bigger push for legislation to let judges rework mortgages in bankruptcy.

"If this doesn't work, nothing will," said Karen Shaw Petrou, the managing director at Federal Financial Analytics Inc. "We've tried a lot of other half solutions that were quibbled and nibbled at … , and we've wasted a year and a half. This needed to be really big and far-reaching, and I think this plan is."

No one — not even President Obama — claimed the plan would be a cure-all.

"This plan will not save every home," Mr. Obama said in his Wednesday speech in Mesa, Ariz., to unveil the plan.

But it was a large step ahead from the previous administration, which relied solely on voluntary efforts and resisted greater government intervention to save homes.

The administration estimated its plan could help 7 million to 9 million homeowners — including 4 million to 5 million borrowers whose mortgages are worth less than their homes and 3 million to 4 million others who are at imminent risk of foreclosure.

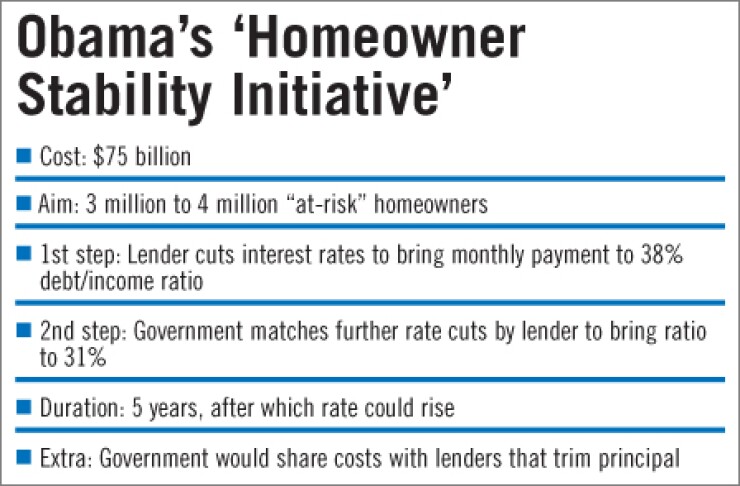

The plan was bigger — and more costly — than expected. The administration said it would spend $75 billion to create a Homeowners Stability Initiative and double its funding commitment to the government-sponsored enterprises, to $200 billion each. The plan was originally projected to cost $50 billion.

Industry observers largely welcomed the plan, agreeing it would go far to avoid foreclosures, but some were already suggesting it needed to go further.

Questions remained whether the plan's incentives would be enough to encourage servicer participation, whether certain borrowers would be left out, and whether a five-year interest rate reset included in the plan is sufficient. "There are significant groups of borrowers who are not addressed by today's announcement," said Josh Denney, an associate vice president of public policy at the Mortgage Bankers Association.

Mark Zandi, the chief economist and co-founder of Moody's Economy.com Inc., said the plan "will help but it won't solve the problem." "Foreclosures will still rise this year; they just won't rise as much as if they didn't have the plan," he said. "I just don't think it's big enough and bold enough to solve the problem quickly."

The plan's centerpiece appears to be the Homeowners Stability Initiative, which is designed to help borrowers who have defaulted on their mortgages or are at imminent risk of default.

Under the initiative, the Treasury Department is to partner with lenders to reduce loans' monthly payments to no more than 38% of a borrower's income. After that, the government is to match further reductions dollar-for-dollar to bring payments down to a 31% debt-to-income ratio.

Lenders are to keep the modified payments in place for five years; after that, interest rates may be gradually increased. Lenders may also choose to reduce mortgage principal, with the Treasury sharing in the cost.

The government will also allow an additional 4 million to 5 million currently ineligible homeowners who got mortgages through Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac to refinance their loans at lower rates. This will be targeted at borrowers who owe more than 80% of the value of their homes. (Please see

But critics said the plan leaves out borrowers who were seriously delinquent and those that had jumbo loans. "It doesn't seem that it provides enough initial relief for people who are at the edge or following the edge at this point," said Gil Schwartz, a partner at Schwartz & Ballen.

For example, the Treasury caps assistance to borrowers at a loan-to-value ratio of 105%. Mr. Denney of MBA said many borrowers in Florida, California, and Nevada would not qualify.

Some consumer advocates also said a five-year time frame would not work, arguing that the modified loans should be fixed for a longer period.

"You're setting the borrowers up to fail again. This is what got us into trouble in the first place," said Bruce Marks, the chief executive officer of Neighborhood Assistance Corporation of America.

The plan is designed to offer a national standard for loan modifications and give incentives to lenders, servicers, and borrowers.

Under the plan, banking regulators must offer loan modification guidance by March 4, and any institution getting Troubled Asset Relief Program funds in the future must comply with it.

The guidance aims to provide servicers protection from investor lawsuits, but several said it did not go far enough, and a change in the law is needed.

The plan would provide a $1,000 fee to servicers for each modification meeting the regulators' modification guidelines. Servicers will also get "pay for success" fees monthly as the borrower stays current on the loan — up to $1,000 a year for three years.

The government will also provide an incentive payment of $1,500 to mortgage holders and $500 to servicers for modifications made while a borrower at risk of imminent default is still current.

Despite the breadth of incentives, it was unclear whether it was enough to entice the industry.

"Will investors pick it up?" asked Scott Talbott, senior vice president of government affairs at the Financial Services Roundtable. "It's a voluntary program and provides thousands of dollars to servicers. Is that enough?"

The administration said it has also developed a $10 billion partial guarantee program with the FDIC to discourage lenders from foreclosing on mortgages that could be viable out of fear that home prices will fall even further later.

Further details were not immediately released, though it appears to differ from a proposal offered by FDIC Chairman Sheila Bair last year. That plan called for offering guarantees of up to 50% if lenders agreed to a systematic modification and the new loan defaulted after six months.

Under the new plan, Treasury will give a 50% partial guarantee for loans modified through the initiative to be paid if home prices depreciate.

Mr. Schwartz estimated the new program may benefit lenders. "You'd probably have steeper declines under this program and more people who would qualify," he said. "That's not necessarily bad. It just costs more."