-

If anyone here is happy to see 2009 in his rearview mirror, it is Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner. Though the financial system is on sounder footing than a year ago, many of his top priorities have stalled or died altogether.

December 29 -

The credit binge has been over for years, but the real hangover starts in 2010 for banks holding a lot of commercial real estate loans.

December 28 -

For most of 2009, bankers were hesitant to forecast when credit woes might peak, but there is a growing consensus that credit problems could be largely resolved a year from now.

December 27 -

Banks are scrambling to find new footing as lawmakers and regulators undermine one of the industry's profit foundations: consumer fees.

December 22 -

WASHINGTON — For nearly 10 years, the top officials at the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. warned about the danger of the declining level of federal reserves, but a funny thing happened when the Deposit Insurance Fund finally went broke in 2009: Nobody cared.

December 21

After their first full year as bank holding companies, the surprising thing about Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and Morgan Stanley is not that they survived this long, but that their business model has.

Many obituaries were written late last year for the concept of the independent investment bank. Conventional wisdom said the firms could not continue without the stability of old-fashioned bank deposits. Popular opinion held that the firms would have to stop putting capital at risk in a market that suddenly revered capital above all else.

But 2009 proved that with a few important tweaks, the investment banking business model could, in fact, continue to function.

The year included a record quarterly profit for Goldman, a blockbuster wealth management deal for Morgan Stanley and a huge resurgence in the shares of both firms. It did not include a combination of either firm with a deposit-taking commercial bank, a pronouncement of crippling capital requirements or a change to the business strategy that Goldman Chief Financial Officer David Viniar succinctly described in the fall of 2008 as "largely to be an adviser, a financier, a co-investor and a financial intermediary for our clients around the world."

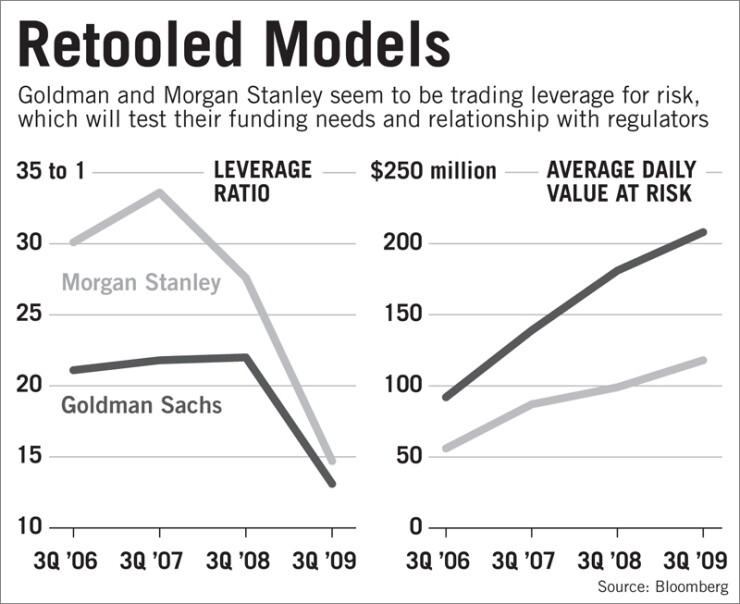

Clearly Goldman and Morgan Stanley are carrying on their work with far less leverage to juice their returns. The ratio of assets to equity is below 15-to-1 at both firms, down from 22-to-1 last fall at Goldman and 28-to-1 at Morgan Stanley. Both firms also have been adjusting their mix of investments and funding sources, making moves to cut their exposure to products like leveraged loans and to reduce their reliance on short-term debt.

But it is hard to say how much of that change is being driven by the firms' conversions to bank holding companies, and how much is simply attributable to the current realities of the market. And that makes it all the more difficult to predict to what degree the firms will find their bank holding company status too constraining when the environment improves and risk appetite swells.

"The profits in the industry right now are not predicated on taking huge risk," said Barclays Capital analyst Roger Freeman, who notes that a strong flow of client business in bread-and-butter products like currencies and bonds has been a sufficient earnings driver of late. But when the flow slows, or assets appreciate or spreads on investment products compress, the firms "will have to bet more principal" to achieve the same returns, Freeman said.

And that is when the impact of the firms' conversions to bank holding companies will more fully reveal itself.

DEPOSITS NEEDED?

The emergency measures that put two freewheeling Wall Street firms under the formal supervision of the Federal Reserve Board were in some way a natural progression once the credit crisis began to unfold.

After the implosion of Bear Stearns & Co., the Fed dispatched representatives to Goldman and Morgan Stanley, and created a new overnight lending facility for primary dealers.

By September, though, the market was desperate for more permanent forms of assurance. Shortly after the collapse of Lehman Brothers Inc., Goldman and Morgan Stanley applied for bank holding company status, which the Fed swiftly granted, and formal examination teams were quickly dispatched to both firms.

At the time, it was widely presumed that the change in status would drive both firms to make a major push to gather deposits.

Goldman kept those expectations in check from the start, with executives noting that deposits could fund only a small portion of the businesses in which the firm was engaged. Even commercial banks such as JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Citigroup Inc. had to use the debt markets to fund many of the Wall Street-style businesses for which they would be forbidden to use deposits as a funding source, they argued.

Morgan Stanley took a more aggressive posture, and began studying plans for building out a retail bank branch network through a combination of organic growth and acquisitions.

In the end, neither company went all out.

Between November 2008 and September 2009, Goldman expanded its deposit base from $27.6 billion to $42.4 billion — a healthy increase, for sure, but not enough to make a huge dent in the firm's funding profile. The increase came mainly from existing institutional clients and private bank customers.

Morgan Stanley wound up scrapping its plans for building a retail bank. Instead, it made a play for Citigroup's Smith Barney unit, in a joint venture that helped bring total deposits at Morgan Stanley to $62 billion at the end of the third quarter.

With deposits now accounting for 13% of the firm's funding base, versus 5% at the end of 2007, Morgan Stanley believes it can get the deposit growth it wants through wealth management, without having to launch a traditional retail bank.

But given the whims of the market and the expectation that regulatory requirements on the firms will get more onerous, this may not be the last word on deposits from Wall Street's remaining pure-plays.

"Some chapters haven't been written yet because the new rules haven't come out yet," said a financial services consultant who asked for anonymity to preserve his relationships with clients. "At some point, they may come to the conclusion that given constraints on market-based funding rather than deposit-based funding, they need to have more deposit-based funding."

RISK AND REGULATORS

The firms also will need to navigate their new regulator's tolerance for risk taking. Though leverage ratios have dropped dramatically at Goldman and Morgan Stanley, the frequently cited risk metric known as Value at Risk, or VaR, has increased, meaning the firms are potentially putting more money on the line on the average trading day.

At Goldman, where the increase has been more pronounced, VaR reached $208 million in the third quarter, versus $181 million for the same period in 2008 and $139 million for the same period in 2007.

Presumably the upward trend would have been cut off at the pass if the Fed was uncomfortable with the numbers it was seeing. Indeed, one logical explanation for an increasing VaR is a corresponding increase in trading revenue, which overall could indicate a firm in a healthier state.

The varying measurements and perceptions of risk represent just part of the challenge the Fed, which declined to comment for this story, faces in overseeing Wall Street's bank holding companies.

Several consultants to the industry report that top-level managers at the firms have acknowledged that they need to change the prism through which they see their businesses. But lower down the totem poll, middle managers carrying out the firms' day-to-day operations seem more obstinate, perhaps because they are not the ones typically invited to meetings with their firms' new regulators.

Spokesmen for Morgan Stanley and Goldman declined to comment publicly about what has changed, and what has not, since their firms became bank holding companies. But chances are, that's a question that cannot be fully answered for several more years, after new capital regulations emerge and get implemented, and the current credit cycle runs its course.