In pursuing plans to open a bank in Pacific Palisades, Calif., Brad McCoy has changed his strategy — twice.

Like a growing number of other would-be organizers in the past year, McCoy gave up on starting a bank and began looking for small banks to buy after running into snags with the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

"We were essentially told by the FDIC, not in so many words, that they aren't approving new ones and that the strategy we should pursue is to acquire a small, clean institution," he said. "They intentionally steered us away."

Then the FDIC announced any state-chartered bank it supervises that is less than 7 years old would be subjected to greater scrutiny, as will some older ones that are acquired by outside investors.

So lately, McCoy has been crossing such banks off his target list. "We had to apply another filter to our search," he said.

For the industry's entrepreneurs, buying a small depository, rather than building one from scratch, has gone from the exception to the rule. The practice started growing more common at the beginning of the year as deposit insurance became harder to obtain.

Further complicating matters, the FDIC is subjecting some groups that buy their way into the industry to a level of scrutiny similar to that for start-ups — regardless of how old the acquired bank is. The agency said it is doing so on a case-by-case basis, depending on the management, business strategy and geographic location of an institution.

Several industry watchers said the FDIC's more stringent handling of both traditional start-ups and these buyers may push more organizing and acquiring groups toward other regulators.

Bruce Crum, a partner at McAfee & Taft, a law firm in Oklahoma City, said he is working with a group of Oklahoma organizers who have switched to an acquisition strategy and have a deal in the works, after finding it too difficult to charter.

Though the target bank is decades old, the FDIC told the buyers that the stricter start-up requirements would apply, he said, noting that the requirements of an 8% leverage ratio and an annual examination schedule have been discussed specifically, though not in writing.

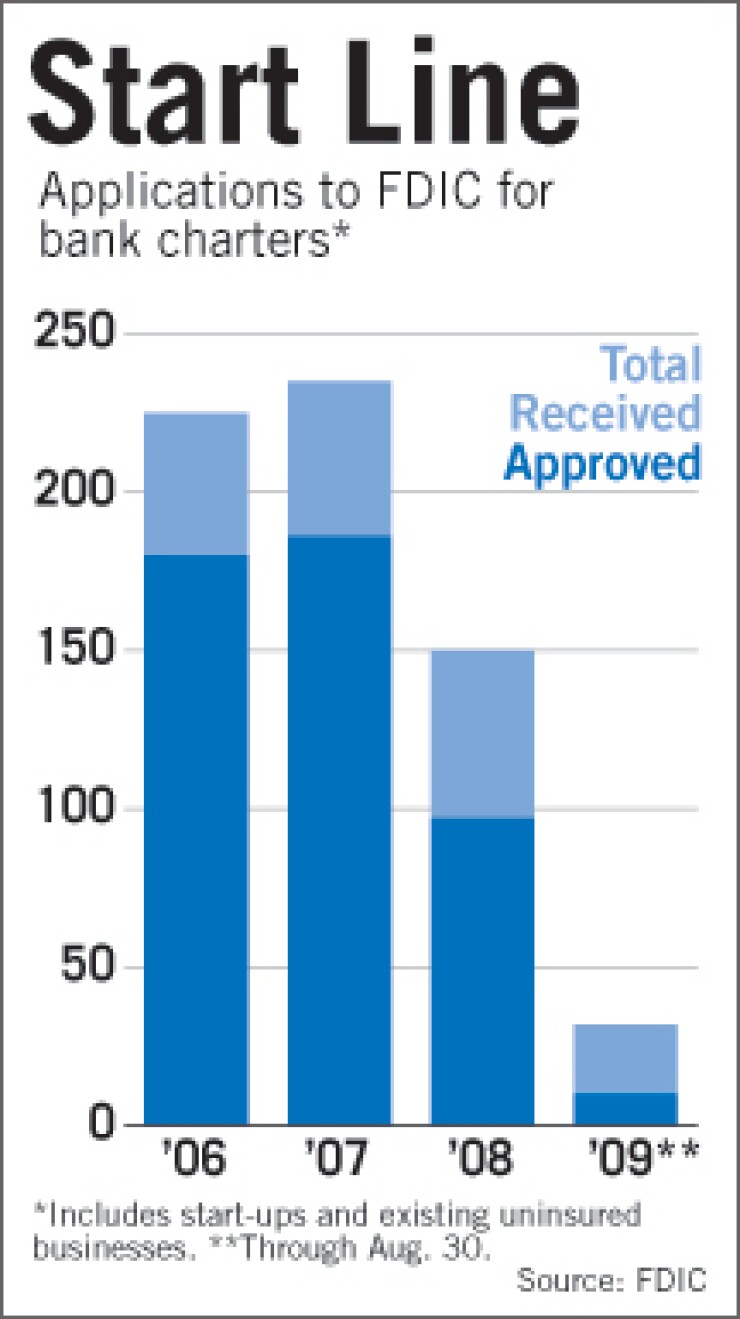

In the third quarter, four new banks were opened, compared to 17 during the same period in 2008 and 44 in 2007. The FDIC declined to say how many organizing groups had withdrawn applications.

The agency reiterated last week that there is no moratorium, formal or otherwise, on new bank insurance and said it has not been encouraging organizers to acquire.

Byron Richardson, the president and chief executive officer of Bank Resources Inc., a consulting and investment banking firm in Atlanta, said he was working with four groups who nixed their charter efforts and are in talks with potential targets.

Of all the organizing groups he knows, "virtually every single one has either thrown in the towel or they have pursued the strategy of either acquiring an existing bank or recapitalization," he said, "meaning they bring in fresh capital" and take control of the bank.

Exceptions remain.

John Polen, for one, said he is on track to open Bank of Palos Verdes in California by early next year.

The start-up, which would be regulated by the Office of Thrift Supervision, is about two-thirds of the way through raising the $16 million it needs to open, he said. And despite not having the FDIC's approval yet, he is confident the regulator will approve insurance for the new bank.

"We met all their requirements, and they have asked for amendments to the business plan, which we have favorably responded to," Polen said. "We are aware several have dropped out. … We are very optimistic."

As of the end of August, the FDIC announced, the three years of a higher level of supervision for new banks it supervises would be extended to seven years. The new policy affects the leverage ratio, which must be maintained at 8%; the frequency with which banks are examined (the exams will occur annually for seven years, instead of switching to every 18 months after the third year); and the business plan, with the requirement now being for a seven-year plan, instead of a three-year plan.

The new business-plan requirement will not apply to institutions that are already older than three years. Newer institutions, however, must submit an updated business plan for years four through seven and get regulators to sign off on changes.

Other regulators — the Federal Reserve, Office of the Comptroller of Currency, and the OTS — said they have not changed their policies on start-up banks and have no plan to do so.

To be sure, the FDIC has a history of more closely scrutinizing banks that are acquired by an investor group, as do the other regulators.

Typically, acquiring groups would submit to the regulators information similar to what an organizing group would. They were often treated like start-ups — getting more frequent exams, having to maintain higher capital ratios and needing to submit a three-year business plan — but there was no set period for applying the added scrutiny.

Daryl Boyls, the president of the two-year-old Allegiance Bank in Houston, said that, even if the extended start-up period had been in effect when his $255 million-asset bank was organized, he would have picked the same state charter.

"I get along really well with the FDIC and the state regulators," he said, noting that he doesn't mind the extended probationary period to which his bank is now subject. "They know me, literally. They know the way I think."

Robert Bonnet was organizing American Bank of Florida in Pinecrest, but the would-be start-up's FDIC approval period expired Aug. 12 without organizers' getting the agency to sign off on its capital plan, he said. Organizers had set a minimum of $11.5 million to be raised.

Bonnet said that the group's plan was approved by the FDIC but that the financial crisis spooked its original investors so that its funding strategy had to change. The group presented a few alternatives to raise capital, but the FDIC rejected them, saying they were a material change to the plan or equated to a change in control.

Now Bonnet is talking with investor groups about doing an acquisition.

"We learned the FDIC would rather any new capital that comes into the market go into existing banks, versus opening a new de novo," he said.

Bonnet said the issue of which regulator is overseeing a target has not come up yet but could be a consideration later.

"What would be the sense in doing this if they are putting that hardship on you for seven years?" he said. "Having opened three other de novos, the first three years, it is not fun. Here you are struggling to make a business get up and running and be in compliance with everything that is already on the table with government regulation. And now we have that extended another four years … . That would be a plus in the equation for acquiring an OCC bank. That is going to be a positive factor in the consideration, but it wouldn't be the driving force for those of us looking for institutions."

Finding a solid bank that is priced right and would fit into the business plan would override which regulator supervised the group, he said.

Jack Shoffner started organizing Florida Shores Bank in Saint Cloud this year. But he said he realized his group would not be able to get the FDIC insurance needed to open a new bank. So he switched gears. His group now has a deal to buy an OTS-regulated institution, which he declined to name. Shoffner said the group has not talked to the regulator yet about the level of oversight that would be imposed after the purchase but does not expect to be treated like a start-up.

"Our thinking is, if we buy an OTS bank that has been in existence for 10 years, that is a change in control and has nothing to do with de novo banking laws," he said.

Shoffner said he does not see the logic behind the seven-year business plan because planning that far out is very difficult.

"You try and do a three-year business plan and hope things work out like you think they will," he said. "I can't imagine doing a seven-year business plan. So many outside factors impact the economy and the bank."

Shoffner said that, even if he did not have plans to buy a thrift, he would steer away from an FDIC bank. "I would lean toward the OTS, and the main reason is, when you give the FDIC a business plan, even though you build into that plan some options for yourself, when the opportunities that aren't presented in the business plan become available and you study them and decide they are a good, sound move in banking, the FDIC comes back and says that is a deviation from the business plan and we don't think you need to do it. … You are locked into a box by your business plan when, in reality, things change from that business plan."

James Rockett, the co-head of the financial institutions corporate and regulatory group at the law firm Bingham McCutchen LLC in San Francisco, agreed that planning for seven years would be difficult and possibly counterproductive.

"I don't think the FDIC can run banks any better than banks can run banks," he said.

Rockett also said the tougher standards for acquisitions may scare off investors.

"There is capital that is anxious to get into the banking system," he said. "I think the likelihood of anybody coming in with a de novo formation is pretty remote. I think most investors are going to want to look to existing institutions and recap an existing institution. If the FDIC makes it impossible for that to occur in a way that there is going to be reasonable profitability, then we are going to see capital flee from the banking sector, which is not what we want."

GreenChoice Bank in Chicago is planning to open its doors as a new bank in the first quarter, in one of the markets hardest hit by failures, said Steve Sherman, GreenChoice's chief operating officer. Sherman said the company is planning to raise $13.5 million to $16 million.

He said the group is still waiting for final FDIC approval.

"We are actively talking with them, and we are confident that we will get that relatively soon," he said.

Sherman said buying is not an option for the organizers because they do not believe the opportunity to find a solid bank at the right price exists.

"There are a lot of people out there trying to buy the dream distressed bank. That doesn't exist," he said. "It sounds good in practice … but what we are hearing is, the banks you can get for a great price you can get for a great price for a reason. The banks that are doing well aren't for sale at the price people would like to see. … It isn't the deal it is cracked up to be."