The Servicemembers Civil Relief Act of 2003 was intended to simplify lenders' compliance obligations to the members of the nation's armed forces.

Two years on, gauging its success is difficult.

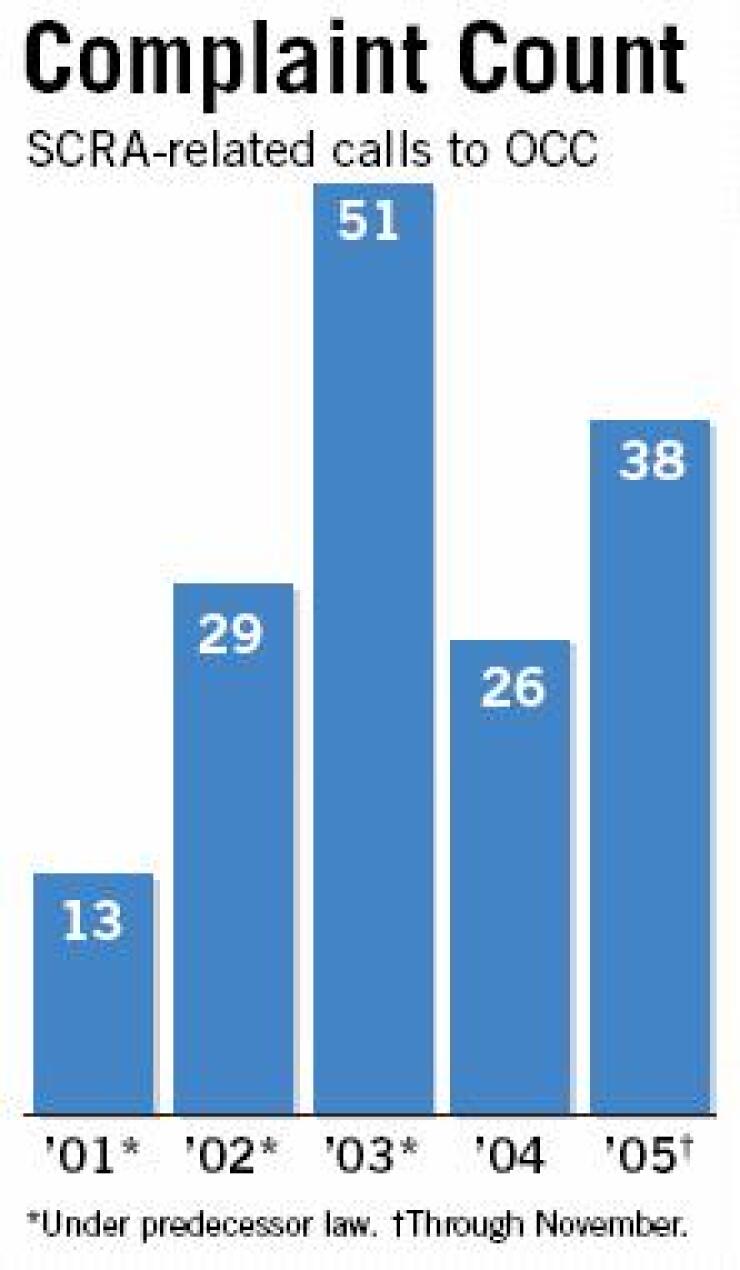

Statistics on the issue are hard to come by and do not paint a clear picture of the situation. President Bush signed the law in December 2003. In the first 11 months of this year the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency logged 38 calls related to it. That is up from up from 26 in 2004 and partly reversed a decline from 51 in 2003.

The law, which is the successor to the Soldiers and Sailors' Civil Relief Act of 1940, requires lenders to reduce to 6% the interest rate that soldiers, sailors, Air Force members, and Marines pay on existing debt from the day they are called up until the day they return to their civilian lives - provided they earn less on duty than they do normally.

Monthly payments on balances incurred before active duty must be reduced. Lenders may not just collect the same amount but put more of it toward principal; nor may they tack the lost interest on to later payments or try to recoup it some other way.

Compliance with those requirements is on lawyers' and activists' radar screens.

John Odom, a former Air Force judge advocate who is now a private lawyer in Shreveport, La., said he knows of 250 to 300 complaints under the law in the last three and half years and has won $3.25 million from lenders in out-of-court settlements of such suits.

Mr. Odom, who has run American Bar Association seminars to teach lenders about the law, described a typical situation:

A small-businessman gets called to active service from the reserves and begins paying off debt at the reduced rate. But an employee at his bank is unfamiliar with the law and assumes that the businessman has fallen behind on the loan.

"As a result, the vet comes back from the war [and] can't borrow two dimes to get his business restarted," Mr. Odom said. "That's where I come in - and take a lot of money off banks, credit unions, and mortgage companies."

Mr. Odom said no one kind of lender is likelier than others to have trouble complying with the law. He has heard complaints about lenders ranging from national banks to federal credit unions operating on military bases, he said.

The law gets particularly dicey when applied to credit cards, said Kevin Flood, another former judge advocate who has worked extensively on these issues.

Only balances incurred before call-up qualify for the 6% rate; interest on any later spending can be assessed at the normal rate. As a result, credit card companies often must break the customer's account into two balances.

Mr. Flood has simple advice for military personnel to avoid mix-ups: "Take whatever credit card you have and lock it in a drawer."

A high-profile series in The New York Times and a recent Senate Banking Committee hearing focused on investment professionals pushing inappropriate products on military personnel. But there is little to suggest that SCRA violations or the resulting hardships on servicemen and servicewomen are widespread or caused by anything but poor communication and ignorance.

An American Banker survey of bank regulators in several states with large military bases found that they had received only a handful of complaints.

The Defense Department says there were nearly 1.39 million active-duty U.S. military personnel at midyear, including 169,000 in and around Iraq. A Federal Reserve spokeswoman said only two of the 1,700 complaints the Fed fielded this year were SCRA-related.

A spokesman for the OCC said SCRA compliance is not a widespread problem.

"One servicemember in distress is an issue to us but industry wide it doesn't seem to be an issue," he said."There's no doubt in the banking industry what the expectations are."

The agency issued compliance guidelines for the banks it regulates six months after the law went into effect.

But Mr. Odom said that SCRA issues are unlikely to find their way into regulator complaint logs. "For the average three-striper at Fort Bliss, Tex., to know he could file a complaint with the OCC is silly," he said. "I've certainly never seen the OCC advertising in the consumer press."

Lenders are hardly the only ones confused at times about how the law applies, according to both Mr. Odom and Mr. Flood. At times, service members who are making more on active duty than they were as civilians incorrectly expect the benefit.

Even some regulators seem not to understand the implications of the law.

Leslie Bechtel, who heads the legal and consumer affairs division of the Georgia Department of Banking and Finance, said it was her understanding that banks need reduce only the interest rate they charged borrowers, not the monthly payment.

"The payment does not have to be reduced," Ms. Bechtel said. "The interest rate has to be reduced."

Not true, Mr. Flood said.

"They have to recast the note as if it were a 6% note from the beginning, or else it wouldn't make any sense," he said. "The idea is to reduce his payments to avoid him going bankrupt."

Banks sometimes misinterpret the circumstances under which the 6% rate kicks in, said Matthew Lee, the executive director of Inner City Press/Fair Finance Watch in Bronx, N.Y.

Under a Freedom of Information Act request, Mr. Lee obtained dozens of complaint letters that military personnel and their family members sent to the Comptroller's Office.

He said they show that some national banks demand excessive documentation from service members or disregard the hardships that military families face.

"It's a little late in the day for institutions to say, 'Our personnel don't know how to handle this,' " he said, noting that the United States has been engaged in major military operations since shortly after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks.

In one letter, a service member wrote a credit card company seeking relief from outstanding bills.

"I am writing you from Baghdad, Iraq, asking, once again, for Bank One to drop my interest rate on these three cards to 6%," wrote the service member, whose name the OCC edited out before releasing the letter.

The writer said he or she was commanding 117 soldiers in Iraq.

"In 60 days my soldiers and I have been hit by 31 roadside bombs. I, personally, do not have time to get involved, nor do I need to be worrying about the bills back home."

A spokeswoman for JPMorgan Chase & Co., which bought Bank One, said the episode was an anomaly and did not reflect the company's policies, which she said exceed the requirements of the law.

"Our policy also reduces the interest rate to 6% on any charges incurred after a person is called to active military duty," the spokeswoman said. "This includes any balance that is created on a credit card line due to an overdraft on a checking account."

She said the company had been in touch with the cardholder and had "addressed the specific concerns."