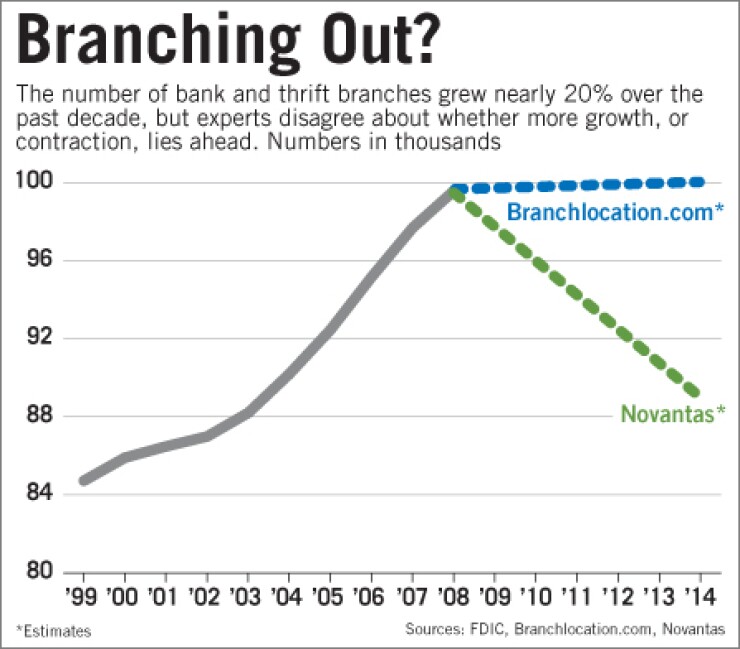

The future-of-branching debate — "brick-and-mortar is dead!" "no, expansion is near!" — is back on, but the two sides have more in common than they might think.

In one corner are the industry experts who forecast a post-meltdown reduction in the number of branches, saying executives have to close branches to raise billions of dollars in capital and return to profitability.

In the other corner are those who argue that if the near future will bring an emphasis on bread-and-butter banking, bankers will have to add branches to whip up deposits.

The predictions vary widely — from roughly 10,000 closings to more than 1,000 additions over the next five years — but everyone agrees on one thing: no matter what happens, the size, nature and location of the branches will change greatly.

"If there is one thing we have learned from this whole crisis, it's the importance of traditional banking, and nothing is more traditional than access to cheap core deposits," said Ken Thomas, the president of Branchlocation.com in Miami.

The two sides are surprisingly united on how to get those deposits.

Though stand-alone branches on street corners might still be superior in high-traffic locations, cost-conscious banks will increasingly shift to smaller branches in strip malls and in grocery and retail stores. Technology upgrades, such as automatic cash vaults and videoconferencing phones, will also reshape the landscape.

As of June 30 there were just over 99,000 U.S. bank and thrift branches, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

Thomas said the number of branches in the country could top 100,000 in the next five years. Underperforming branches will be weeded out, Thomas said, but total numbers will increase to attract more deposits, particularly in high-growth markets fed by immigration, such as Southern California, Arizona and Florida.

Tom Brogan, a research director at TowerGroup Inc., an independent research firm owned by MasterCard Inc., is projecting a net gain of about 1,200 branches in the U.S. by 2013.

Banks will likely keep building smaller branches to save costs, Brogan said. A typical branch is currently about 3,500 square feet, and he expects that average to shrink to about 3,000 square feet. Strip mall branches and in-store branches typically cost $700,000 to $1 million to build, and stand-alone branches about $2.7 million each, he said.

"The main driver of branch usage is still convenience, so if I can spend the same amount of money on six or seven smaller locations as I do five, I can provide better, more convenient service to my customer base," Brogan said.

Fewer tellers will work at these sites, and banks will likely use more technology such as video phones to arrange conversations between customers and experts in mortgage lending or wealth management, Brogan said.

In interviews, a handful of bank officials backed up some of these arguments.

Richard Hartnack, the head of consumer banking at U.S. Bancorp, said the Minneapolis company will likely have a larger branch network in five years.

"We don't have branches in all the places we need to best serve our clients," Hartnack said, particularly on the western end of its territory.

Currently U.S. Bank has 2,867 branches, but Hartnack would not estimate how many it would have in 2014, because acquisitions would factor into that projection.

JPMorgan Chase & Co. will also have a net gain by then, said spokesman Tom Kelly.

Though it has closed 300 overlapping branches in New York, Chicago and Texas since buying the banking operation of Washington Mutual Inc. in September, and it expects to close 100 more by yearend, it plans to open 100 to 150 branches a year indefinitely.

It has roughly 5,200 branches now.

"The branch is the single most important place for people to open accounts," Kelly said.

TD Bank, the U.S. unit of Toronto-Dominion Bank, plans a net gain of about 30 branches for the next two years and then at least 50 each year after that, said Fred Graziano, executive vice president of retail banking.

That strategy can help the bank meet its goal of being ranked one of the top three in branch count and deposit share in each of its markets.

Not everyone believes branch networks will continue to expand. Dave Kaytes, a managing director in the New York consulting firm Novantas LLC, said there could be as many as 10,000 fewer branches in the country in the next five years as the industry makes slashing costs its top priority.

Kaytes estimated that the industry needs about $800 billion to $900 billion in additional capital over the next several years to repay funds from the Troubled Asset Relief Program and to placate regulators. However, banks as a group will likely make about $100 billion to $150 billion in net income a year, so the industry will have to find more ways to lower expenses.

"Banks have done a very good job of squeezing costs out of their headquarters — outsourcing operations, consolidating back offices, cutting various lines of business, reducing purchasing costs," Kaytes said. "The only place left is reducing the very-high-cost branch network," which typically amounts to 60% of a bank's expenses.

Though smaller branches can cost less to build and maintain, Kaytes contends that there are considerable fixed costs at every branch and that a greater number of smaller branches will not necessarily cost less than a network of fewer, but larger, branches.

Bob Hedges, managing partner at Mercatus LLC, a Boston consulting firm, agreed with Kaytes that there could easily be 10% fewer branches in five years. Consolidation within the industry will play a large part, as acquirers close overlapping branches and smaller banks go under.

But Richard A. Soukup, a partner with the Chicago office of the consulting firm Plante & Moran PLLC, said he expects branches to maintain their customer service lead in the foreseeable future. He conceded there could be a net reduction in branches in the near term in markets like Chicago as a result of consolidation. And there may come a time that alternative channels will gain in prominence as younger generations mature — but that will not happen soon, he said.

"For years, everybody's been predicting the death of brick-and-mortar, but it just hasn't happened," Soukup said.