-

Far from being the big winner under Senate Banking Committee Chairman Chris Dodd's regulatory reform bill, the Federal Reserve System would undergo radical changes — including a likely consolidation of its 12 district banks — if the legislation were enacted.

March 16 -

Senate Banking Committee Chairman Chris Dodd introduced a moderate regulatory reform bill on Monday, packed with nods to Republicans in an effort to gain some bipartisan support.

March 15 -

Senate Banking Committee Chairman Chris Dodd on Monday released a broad outline of his regulatory reform bill, which heavily reflects input from Republicans who still say they oppose the bill.

March 15 -

Senate Banking Committee Chairman Chris Dodd's regulatory reform bill would overhaul the way financial companies are overseen and how troubled companies are unwound. But the 1,300-plus page bill contains many other provisions, including these ...

March 15

WASHINGTON — The latest regulatory reform proposal from Senate Banking Committee Chairman Chris Dodd would have far-reaching implications for day-to-day operations at most banks and thrifts, changing which regulators oversee them and potentially broadening the number considered systemically important.

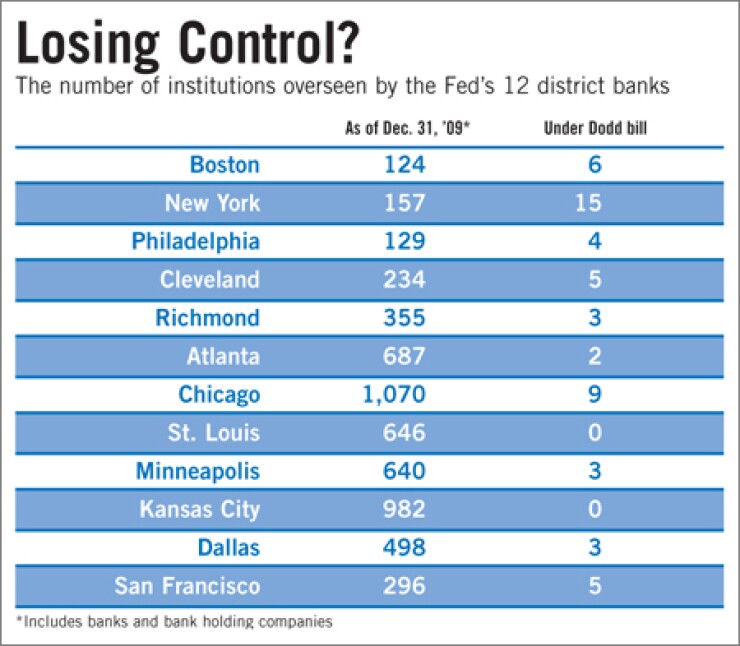

A key provision would leave the Federal Reserve Board in charge of the 55 holding companies with more than $50 billion of assets but give oversight of all the rest to the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. — agencies that have never supervised holding companies.

That would be a significant shift from the current system, and it fueled debate Tuesday over whether it would unnecessarily upend supervision of most institutions, complicate the system and classify more institutions as "too big to fail."

"It creates an incredible disruption to the regulatory apparatus because most institutions are going to get a new regulator," said Lawrence Kaplan, a lawyer at Paul Hastings.

The vast majority of banks operate within a holding company, which subjects them to Fed supervision. The FDIC says there are 4,519 one-bank holding companies and 426 companies that control two or more banks.

For the roughly 2,200 banks that operate without a holding company, supervision would only change for state-member banks, which would fall under the FDIC.

But most holding companies would shift from Fed oversight to supervision by the OCC or FDIC. For multibank holding companies, its largest charter would determine which agency regulates it.

Some said the provision is confusing, noting that Dodd's original bill, introduced in November, consolidated all the regulators into one.

Now he is making two agencies that lack any experience in regulating holding companies into holding company supervisors, while preserving the Fed in that role for the biggest companies.

"This doesn't make a lot of sense," said Dean Baker, the co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research. "The original intention was to get rid of regulatory shopping, and I don't know you can say you've done that. You would still have your choice between the Fed, OCC and the FDIC. Obviously, there is a size criterion, but if you are doing an acquisition or a spinoff, you can change that, and I'd rather that not be the case."

For some banks, the switch could be a good thing. Small-bank holding companies with a national bank subsidiary would go from two regulators to one, for example, and those with a state bank subsidiary would go from three supervisors to two.

But Richard Spillenkothen, a former director of banking supervision and regulation at the Federal Reserve and now a director in Deloitte & Touche LLP's regulatory and capital markets consulting practice, said the move cuts both ways from a policy perspective.

One "potential drawback is, you lose, in some sense, this notion of two sets of eyes, where sometimes two regulators see things in different ways," he said.

"If you have the bank regulator also regulating the holding company, you lose a different perspective of having two parties look at the same situation. But on the other hand, there are obviously some benefits because when you assign the holding company supervision to the primary regulator of the lead bank, it reduces the potential for overlap."

Observers were at odds over whether the $50 billion cutoff makes sense; many said the number appeared to have been plucked out of thin air. They said it was an arbitrary number picked to reach a political compromise rather than achieving a clear public policy objective.

Still, some said it might work.

"If you are going to do this on the basis of assets — this one isn't bad," said Ellen Seidman, a former director of the Office of Thrift Supervision. "This was a compromise to try to preserve the dual banking system … because community banks really are different. This division makes sense."

But Kip Weissman, a partner at Luse Gorman, said he has concerns that the $50 billion cutoff would unfairly label too many institutions as systemically important.

"Fifty billion is too low," he said. "Most disinterested parties would agree that institutions that are under $100 billion are not systemically significant, at least not for depository institutions. Hedge funds might be another story."

Many banks with $50 billion to $100 billion of assets could face tougher capital standards and pay extra fees to fund a proposed resolution fund for systemically important banks.

"It's too low, and it is unfair," Weissman said. "It's probably going to cost them some money on their stock values."

The market may view all banks in this class as "too big to fail," he added.

"There is no doubt that the market is going to treat them differently," he said. "It creates artificial incentives and artificial decision-making. It would be unfortunate if the regulation, rather than the economics, would determine decisions."

But many observers said that it is pretty clear that only a handful of the largest institutions are considered "too big to fail" and that the new designation would not change that perception.

"I don't think that putting them officially with the Fed in itself makes much difference on too big to fail," said Douglas Elliott, a fellow at the Brookings Institution.

"You may argue over a couple banks on the edge … . I think everyone's pretty confident that the federal regulators could let a $60 billion asset bank go under."