-

Though recent improvements in delinquency rates for credit card debt have closely tracked declines in the pace of job losses, the industry faces a tough climb out of a cycle of devastating losses.

September 4 -

If credit card loan performance is indeed turning around, it appears to be doing so the fastest at American Express Co., giving the company an opportunity to ramp up business.

August 26 -

Some large issuers posted continuing signs of improvement in credit card performance in monthly reports for July.

August 17 -

Given the glimmers of improvement in second-quarter results, credit card lenders are hoping for an endless spring.

July 24

For years, issuers strove to make their credit cards "top of wallet" — the first one a consumer pulled out when making a purchase. Today, these lenders are jockeying for a different prize: whatever's left in the wallet.

Consumers "have a limited pot of money every month to pay bills," said Liz Jordan, a senior manager at the governance, regulatory and risk strategies practice of Deloitte & Touche LLP. Issuers "know that they are potentially competing against other debts," including on competitors' cards. "They really want to be in line first."

That's because the first creditor to cut a troubled consumer a break, such as by waiving fees or interest, could have the best chance of securing repayment, if not in full. Though the strategy has risks — most notably, that the borrower will just fall behind again — borrowers sinking into distress face difficult choices about which bills are most important to them, and friendly overtures can be well received.

As a result, "collections has become a marketing game," said Vijay D'Silva, a director and co-head of the payments practice at McKinsey & Co. Inc. "Simply, the call-and-collect approach doesn't work as well as it used to, especially if you're competing against other lenders for the same dollar."

Lenders have been experimenting with changes to formulas that determine when they cut slack to late borrowers, and how much slack they give. At American Express Co., the scale of expanded breaks given to borrowers has been significant enough to put a dent in interest income.

BOTTOM OF THE WALLET

Jim Bramlett, a managing director at the consulting firm Novantas LLC, described the industrywide move toward larger and more generous settlement offers so far as "a blunt instrument" reflecting "the degree of distress in the industry."

Earlier this year, "there was this foreboding sense of panic," leading issuers to take bigger risks to avoid falling "further behind the curve," Bramlett said.

David Sisko, who runs the default management group at Deloitte, said that because of heavy losses, credit card lenders "need to try dramatic things to get dramatic results."

At a meeting with investors and analysts last month, Daniel Henry, Amex's chief financial officer, said the company has increasingly pursued the minimum due as opposed to the entire balance; turned to litigation against customers with high balances; and forgone interest charges and fees on severely delinquent accounts.

Amex would not say how many cardholders are getting a break under the new collections practices, or how big the breaks typically are.

The company also declined to say how much they have helped its delinquency rates — though it did say delinquencies would have fallen in the second quarter without them.

(Amex has forecast that the annual rate at which it writes off U.S. credit card debt as uncollectible peaked at 10% in the second quarter.)

The object of the shift in collection practices is "to keep certain card members active and, over time, they turn out to be really good long-term customers," Henry said at the meeting.

"Another portion of those may eventually write off, but that will provide us the opportunity to have a higher level of collection from them."

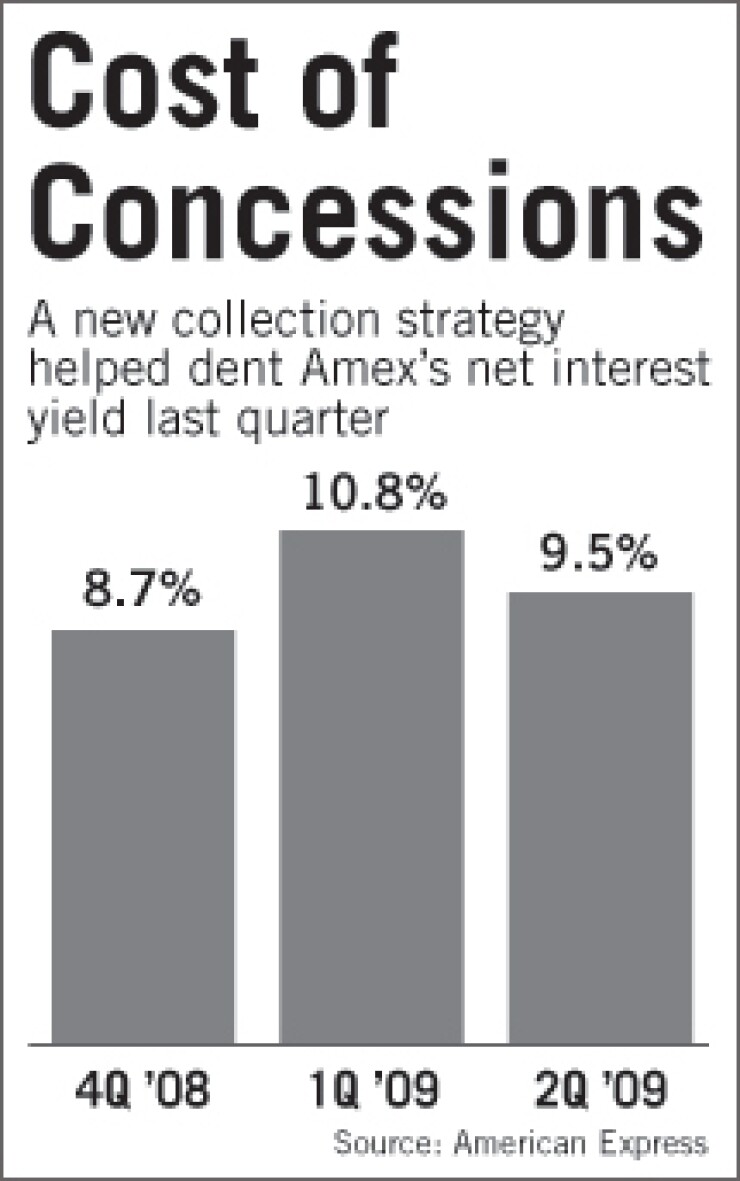

The new collections approach largely explains a 1.3-percentage-point drop in the net interest yield on Amex's U.S. credit card portfolio from the previous quarter to 9.5% in the second quarter, Henry said.

(The net interest yield had rebounded 2.1 percentage points from the fourth quarter, to 10.8% in the first, as a severe funding crunch for financial institutions unwound and Amex raised prices on 55% of its portfolio.)

Bank of America Corp. said it modified about 1 million credit card loans last year and expects to modify 1.2 million this year. It would not say how the loans it modified have performed.

Capital One Financial Corp. said that it now contacts borrowers sooner after they show signs of falling behind, among other changes it has made recently in dealing with troubled borrowers.

Citigroup Inc. would not say whether it has changed its approach to collections because of increases in delinquencies. Samuel Wang, a spokesman, said its programs to help troubled borrowers, including one that offers "matching payments which go towards reducing the customer's outstanding balance," are part of an "ongoing process."

Discover Financial Services said it has "done some fine-tuning" to its collections practices "in the face of the challenging environment."

JPMorgan Chase & Co. declined to comment for this story.

D'Silva said the nature of unsecured debt has long made credit card lenders more sophisticated than other financial companies about collections — without collateral, the card issuers have to rely more on models of consumer behavior, for instance.

But amid a severe rise in credit losses and a multiplication of the potential sources of personal financial distress — including the strain of mortgage debt — the "palette" of forbearance strategies for late borrowers "has increased dramatically," D'Silva said.

Lenders "have introduced five-year [term loan] plans, for instance, that you didn't see as often two years ago," he said. One reason is that borrowers increasingly do not have the wherewithal to make big one-time payments.

Alan Mattei, another managing director at Novantas, said increases in "roll rates" — the percentages of late borrowers who proceed from being one month late to deeper stages of delinquency — prompted lenders to move up settlement offers in an effort to secure some kind of payment before the borrower's financial condition deteriorates beyond repair, or another creditor claims whatever can be salvaged.

Lenders "have to stand out of the crowd," Mattei said. "You need to make some sort of appeal to the person in a way that's going to say, 'I'm trying to work with you here."

"If you can create a bit more affinity between the rep and the customer, you're likelier to get through and likelier to get them to pay what little bit they can in your favor."

But it can be a struggle for large organizations to field efforts that successfully appeal to borrowers' emotional needs, and lenders have been strained by the challenge, Bramlett said.

While lenders are willing to give more ground to troubled borrowers, he said, operational obstacles to implementing wholesale changes to collections and queasiness over the economics of forbearance have hamstrung the industry.

"It's hard for issuers to make a confident forecast as to whether or not they're better off in making a major concession. It's quite a bet," Bramlett said.

"It takes six or 12 months to actually make any kind of a reliable read on" whether bigger concessions produce a better outcome for a lender — for instance by measuring results against a control group that was not offered more generous terms. "Anything that they do today is an article of faith."

As Mattei put it, "Even if I decided to take that leap of faith, how do I now implement that and train that across 8,000 people on the phones? And my systems changes take six to 12 months, and training cycles for that many people can take another month or two at a minimum."

Moving early with large breaks also runs the risk of making needless concessions.

For one thing, people who lose their jobs can find new work, and late borrowers can regain their footing.

Moreover, as in the mortgage sector, where borrowers frequently fall behind again after receiving a modification, there is considerable doubt about the effectiveness of concessions.

CREDIT MIRAGE?

Some analysts attribute much of a recent improvement in delinquency rates to lender forbearance that is only masking credit problems that will emerge later.

A temporary reduction in the minimum monthly payment for a borrower who is trying to secure a mortgage modification, for example, may allow the borrower to stay current for a time, Sisko said.

But without a fundamental improvement in the employment picture, the borrower's financial situation may not improve. "Their situation is probably not temporary," he said.

Rick Wittwer, who oversaw collections and recoveries as an executive at Washington Mutual Inc.'s cards unit and at Providian Financial Corp., said that because settlement installments can exceed the minimum payment amount under the original contracts, such stressed accounts can be classified as current.

Overall, Wittwer reckoned that various forbearance tactics may have lowered delinquency rates by 20 to 30 basis points in recent months.

Though regulators require reserves reflecting exposure to customers who have been granted forbearance, Wittwer said, the forbearances still cloud the picture provided by delinquency rates and raise questions about the strength of the turn suggested by figures in recent months.

American Express is cautious about how its new tactics will affect its credit performance.

At the meeting last month, Henry said the company had nearly doubled its reserve coverage of late U.S. card balances from the year before, to 254% in the second quarter, in part because of uncertainty over the changes in its approach to collections.

Sisko said, "Until we see core improvement in the macroeconomic factors that are causing the high delinquencies, you're going to see a higher than 50% redefault rate."