WASHINGTON — Community banks are urging Congress and regulators to exclude Paycheck Protection Program loans from their total asset amounts out of increasing concern that participation in the government's pandemic relief effort will trigger new burdensome regulations.

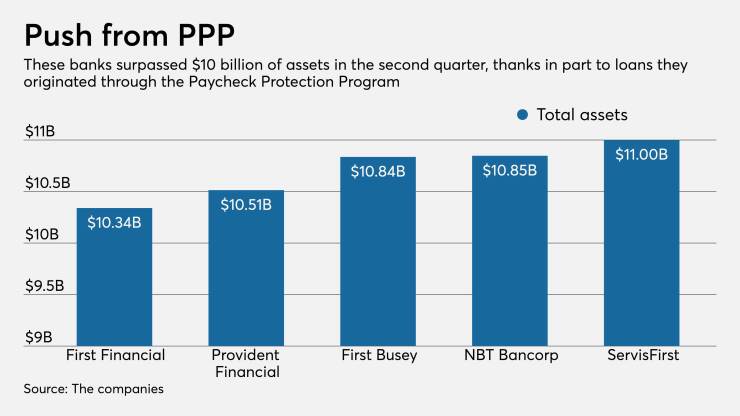

Participation in the coronavirus loan program for small businesses has helped push numerous institutions' asset totals beyond $10 billion. Crossing that key threshold brings supervision by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, pricing limits on debit interchange fees and required compliance with the Volcker Rule ban on proprietary trading, among other things.

"Our best guess was that absent another M&A opportunity, we would not go over that level in 2020," said Van Dukeman, president and CEO of First Busey Corp. in Champaign, Ill., which went past the threshold this year thanks in part to PPP loans. "But we are there now.”

The Independent Community Bankers of America urged lawmakers last month to pass legislation ensuring that PPP loans on banks' balance sheets do not result in institutions getting hit with a flood of new rules.

“There’s all these regulatory demarcations that kick in based on asset size,” said Paul Merski, group executive vice president for congressional relations and strategy at the ICBA. “Banks are going to face being tripped up by these regulatory thresholds that could end up costing them additional money or … losing revenue.”

The PPP closed to new applications on Aug. 8. Banks receive federal funding to back the loan issuances, but the financing remains on banks' balance sheets. Borrowers can seek to have the loans forgiven if they meet program criteria. However, with the

According to the Small Business Administration, over half of the more than 5 million of total PPP loans were issued by institutions below $10 billion of assets, and those institutions accounted for nearly half of the $525 billion that was lent.

“When the PPP program came along, the banks wanted to be able to help the businesses in their community,” said Rebecca Laird, of counsel at K&L Gates. “So they wrote these loans and they wrote them relatively quickly, so you end up with $2 billion worth of new loans in a community or state that you never had before on the books of the banks. So it was a very big jump.”

The new regulations for banks could kick in because PPP loans have been sitting on banks’ balance sheets longer than they anticipated.

“The intent of Congress and the intent of most banks is to quickly convert these into grants, but as we’ve seen the process has become much more time consuming, much more delayed, much more complex, where these PPP loans could be remaining on the banks’ books a lot longer,” Merski said.

Under the Dodd-Frank Act, when a bank hits the $10 billion asset threshold, the CFPB becomes the primary agency responsible for enforcement of federal consumer finance laws. If an institution has $10 billion of assets at the end of the calendar year, it is also subject to the cap on debit interchange fees, a measure added to Dodd-Frank by Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Ill.

The $10 billion asset threshold became even more significant after Congress passed a regulatory relief law in 2018 known as S 2155. The law exempted banks under the threshold from the Volcker Rule if their trading assets were less than 5% of total assets, made it easier for banks below $10 billion to comply with the CFPB's "qualified mortgage" rule and allowed banks under the threshold to use a simpler measure of capital strength.

The amount of time that PPP loans remain on banks’ balance sheets will likely determine whether they are subject to new regulations. Jeff Naimon, a partner at Buckley, said that new regulations typically kick in after banks have operated with more than $10 billion of assets for four quarters.

Naimon cited a hypothetical example of a bank with $9.5 billion of assets extending "PPP loans that might take them briefly above the $10 billion threshold."

The bank "could end up above the threshold for a quarter,” Naimon said. “But it’s not likely to be significant as long as assets fall back beneath the threshold in subsequent quarters.”

He added that a number of banks with less than $10 billion of assets are “pretty intentional about” avoiding the threshold in order to avoid new regulations.

But not every institution has been so fortunate. In some cases, banks that were planning to exceed $10 billion at some point have met the threshold ahead of schedule because of both PPP and the massive growth in liquidity from the government's coronavirus response.

Other institutions that had been on the cusp of hitting $10 billion, or just went over, likely could have managed their asset total below the threshold were it not for the PPP.

Dukeman said First Busey had less than $10 billion of assets at the end of 2019 but has since met that threshold, in part because of the Paycheck Protection Program and other liquidity activities of the Federal Reserve. The bank had $10.8 billion of assets at the end of the second quarter. It would have had only $10.1 billion without its PPP loans, according to securities filings.

“There’s been a hoarding of liquidity and the Fed has been flooding the system, so there has just been a tremendous buildup in deposits,” Dukeman said.

He said the bank had been preparing to be regulated like a $10 billion billion-asset institution but did not anticipate reaching the level so soon.

“The bank has been relatively acquisitive over the last five years or so and ... planned at some point to go over $10 billion,” Dukeman said. “So we knew this would happen at some point."

First Financial in Abilene, Texas, would have stayed below $10 billion of assets without the inclusion of PPP loans, according to its filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission. The institution reported about $10.3 billion of assets as of June 30. Similarly, PPP originations helped push ServisFirst Bancshares in Birmingham, Ala., above the threshold. The bank reported about $11 billion of assets last quarter.

Dukeman said the financial impact of the Durbin amendment will likely be substantial.

“The big concern I think is the financial impact of going over $10 billion with respect to the interchange fee that was part of the Durbin amendment,” he said. “It’s a material number, as it has been for all banks going over $10 billion.”

But he added that “there is a pathway that could be achieved” in which the bank falls back below $10 billion before the end of the year.

In a letter to the Senate Banking Committee on Aug. 31, ICBA President and CEO Rebeca Romero Rainey urged Congress to pass legislation “to direct the federal banking regulators to exclude Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans from bank and bank holding company asset threshold calculations.”

But Laird of K&L Gates said that regulators could determine on their own that PPP loans are left out of asset calculations used to determine compliance with certain rules, particularly since regulators have eased other rules in response to the coronavirus pandemic.

“While the statutes are pretty absolute, providing that if an institution is over a certain asset size, then it is subject to whatever it is, CFPB, Volcker, Durbin, in a number of cases, the regulation requires that the institution has been over $10 billion for a number of quarters before there are consequences, so that provides for some flexibility,” Laird said. “It is also the case that the regulators might take the same position they’ve taken on other things COVID-related and not immediately levy the consequences of being over a threshold.”

Merski said it would likely be easier for regulators to decide administratively that PPP loans are excluded from the asset size calculation than for Congress to pass a law.

“To get anything done legislatively seems to be a tremendous challenge these days,” Merski said.

Even if a bank would normally fall under the $10 billion asset threshold without PPP loans sitting on its balance sheet, new regulations would likely kick in eventually because the bank would naturally break the threshold over time, said Ed Mills, a policy analyst at Raymond James.

“If someone is put over the asset threshold for PPP lending, it seems as if they would be close enough that within a few years they would be over the threshold anyway,” Mills said.

Mills said that banks' concern about PPP loans triggering new regulations is indicative of the industry's general focus on asset thresholds since Dodd-Frank passed in 2010. Critics of the law have charged that the $10 billion cutoff as well as thresholds that kick in for larger institutions were arbitrary, and punish institutions considerably smaller than the megabanks that receive more of the blame for the 2008-09 financial crisis.

“We are a decade-plus past the passage of Dodd-Frank and the fight of what the right threshold is, is far from over,” Mills said.

A spokesperson for the American Bankers Association said that PPP loans’ impact on bank regulatory obligations is another sign that inflexible asset thresholds are not working.

“Unfortunately, by helping to absorb the economic shock of the pandemic, some banks will cross one or more of nearly a dozen arbitrary asset thresholds that trigger additional scrutiny, cost, and legal obligations,” the spokesperson said. “ABA has long believed that inflexible asset thresholds come with unintended consequences that can harm banks and their customers, and the current situation brings these concerns back into focus.”

Paul Davis contributed to this article.