Whether the economy remains weak, hampered by continued rapid spread of the

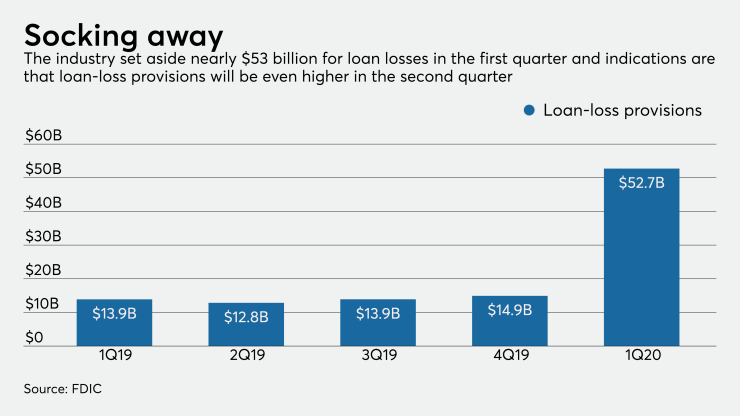

The pandemic-imposed recession is battering the retail, hospitality and energy sectors — and broadly sales for a range of other businesses — leaving banks to conservatively assume that more borrowers will struggle to make loan payments, even if the economy gradually recovers in the second half of 2020.

“Bottom line,” D.A. Davidson analysts said in a June report, “we expect to see continued reserve build over the balance of the year, with a hand-off to more elevated” charge-offs later in 2020 and into next year.

When second-quarter earnings calls get underway in July, executives at community and regional banks are likely to field an abundance of questions about credit quality. The hope is that, by mid-July, bank executives will be able to shed meaningful light on what lies ahead based on the performance of their loan books and their assessments of customer sentiment and expectations.

One telling sign could be the direction of loan deferrals. Late in the first quarter and early in the second, banks agreed to defer scores of commercial loan payments, often for 90 days. Will those borrowers be able to resume payments on those loans? Will they seek to extend deferrals? Or will they throw in the towel on their businesses, forcing banks to charge off more loans?

“Almost everyone believes the amounts are as high as they’ve ever been, and so the most important question in the industry right now is at what rate those deferrals translate to losses,” said Joseph Bonner, founder of the consultancy Community Bank Advocates and a former bank CEO.

Even with some clarity on the deferral front, Bonner said, most banks would be wise to brace for continued economic weakness and a choppy recovery. Provisions soared in the first quarter. He anticipates further increase for many banks in second-quarter results. He noted that Federal Reserve officials recently predicted that unemployment, currently above 13%, could still hover nearly 10% by the close of 2020.

“I believe that the more conservative view is the prudent one,” Bonner said.

Banner Corp. in Walla Walla, Wash., for one, in June provided an updated look at its anticipated second-quarter provision expenses. It said provisions could range from $27 million to $36 million. At the midpoint, that would exceed the average analyst expectation at the start of June by $12.4 million, according to Stephens analyst Gordon McGuire. The Banner projection, at the midpoint, includes $6 million for charge-offs and impairments.

The $12.8 billion-asset Banner recorded a provision of $21.7 million for the first quarter, more than 10 times the year-earlier level. The bank said proactive downgrades on modified and at-risk loans — based on economic forecasts that weakened since the first quarter — drove the projected second-quarter increase.

“We anticipate more banks will guide toward higher provisions,” said Janney analyst Tim Coffey.

First Bancorp in Southern Pines, N.C., disclosed on June 17 that it recorded $18 million in loan-loss provisions in April and May, or more than triple what it set aside in the first quarter. The $6.4 billion-asset company has granted deferrals for loans representing about 17% of its overall portfolio on March 31.

The biggest credit quality problems are expected to lie in industries hardest by the government-imposed lockdowns that closed

But expectations that weaker credit will spill into other areas are mounting and may continue to do so, particularly if the economy fails to rebound in the third quarter.

Among the largest and most battered is the energy industry, where demand for fuels plummeted as the pandemic led to travel cutbacks and lower demand for the power used to run businesses and industrial operations. More than a dozen U.S. oil-and-gas producers filed for bankruptcy in the second quarter, and the law firm Haynes and Boone, which tracks Chapter 11 filings, expects more to come. Oil prices have recovered some in recent weeks as transportation increases, but prices remain well below pre-pandemic levels.

“It is reasonable to expect that a substantial number of producers will continue to seek protection from creditors,” Haynes and Boone said in a report.

The $133.5 billion-asset Regions Financial in Birmingham, Ala., for example, says it is obvious that energy is vulnerable.

“We look at the energy book [and] we know there's stress. We know there's going to continue to be stress,” Barbara Godin, Regions’ chief credit officer, said at a June conference. “Glad that the price of the barrel of oil has come back up, but notwithstanding, it is going to shake some players out. So all eyes on that portfolio.”

Extensive federal stimulus packages, notably including the Paycheck Protection Program for small businesses, could minimize the overall damage. Banks anticipate that the bulk of PPP loans will be converted to government grants. Should that funding bridge commercial borrowers from current economic weakness to recovery, and should a substantial share of clients that sought loan deferrals resume payments in the third quarter alongside increased business activity, many banks could avoid steep credit losses that would otherwise imperil full-year profits.

“In the third quarter, we could see the PPP stimulus run out, a lot of the loan deferrals could end, a lot of the unemployment benefits will run out,” John Corbett, the CEO of the $35 billion-asset South State in Winter Haven, Fla., said in an

At the same time, said bank investor and Iron Bay Capital President Robert Bolton, many banks are now

“So in addition to credit, there will be a lot of eyes on PPP, on the impact of government stimulus and on banks’ ability to maintain their margins,” Bolton said. “The very good news is that banks went into all of this exceptionally well capitalized. I think, as an industry, they can and will weather the tremendous disruption that we’ve seen.”