Concerned about rapidly growing fraud in the automated clearing house system, bankers and network operators are stepping up their efforts to fight back against criminals.

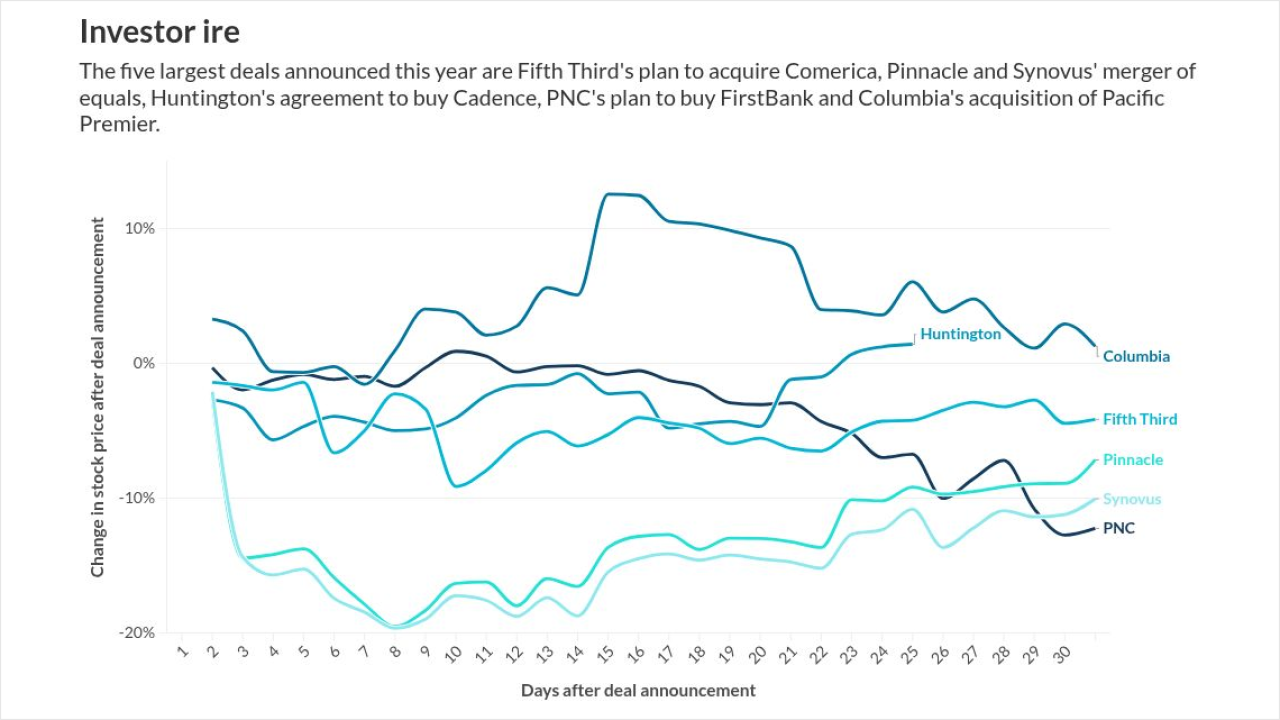

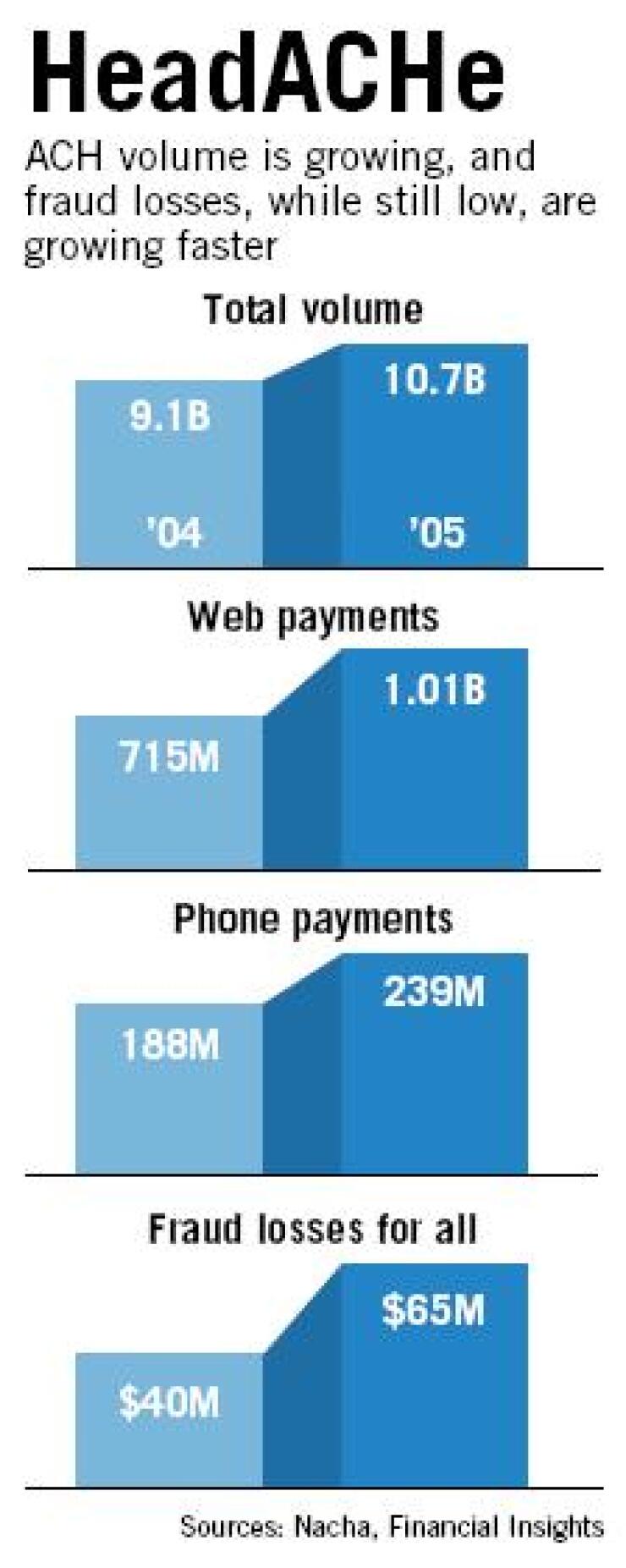

Though the problem remains small in absolute terms, the increased volume of ACH transactions, and of two of the most recent ACH formats in particular, has made the payments system more accessible to criminals.

The banking industry's losses from ACH fraud rose 62.5% last year, to $65 million, according to Financial Insights Inc., a Framingham, Mass., research unit of International Data Group Inc.

Alenka Grealish, the manager of the banking group at the Boston research and consulting firm Celent LLC, said much of the increase stemmed from "e-check" transactions, which let people initiate ACH debits over the phone or the Internet with nothing more than a valid bank account and the corresponding bank routing number.

Those two transaction formats, WEB and TEL, "have opened the doors to new fraudulent acts," Ms. Grealish said. Both were introduced in 2001.

ACH fraud first appeared on bankers' radar in about 2003, and the problem has grown steadily since, she said. Businesses, which often have large balances spread over multiple bank accounts, are the most common targets.

Though the losses hardly compare with those resulting from other types of fraud - the American Bankers Association says check fraud cost the industry $677 million in 2003, the latest year for which figures are available - the dramatic growth rate has clearly caught the industry's attention.

To help combat ACH fraud, the Federal Reserve banks said this week that they are about to launch the FedACH Risk Origination Monitoring Service, which will allow originating institutions to set caps on ACH debits and credits for individual companies or for specific bank routing numbers.

Richard R. Oliver, an executive vice president at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta and the manager of the Federal Reserve Board's Retail Payments Office, said 10 financial companies are pilot testing the service now, and the central bank plans to make it generally available next month.

The service will help small originators, which may currently rely on manual processes, monitor ACH payments and prevent fraud, Mr. Oliver said. Large banks, which sometimes provide routing numbers to third parties such as payment processors or payroll companies to connect directly to the FedACH network, would also benefit, he said.

"A lot of banks have in-house systems, but no in-house system can monitor a third party that has its own routing number," Mr. Oliver said.

Spotting fraud is the main concern, but the service can also guard against operational risk, he said, "to make sure that nobody makes a huge operating error."

Other antifraud measures are on the way.

This quarter the Clearing House Payments Co. LLC of New York expects to introduce a service that uses artificial intelligence to monitor its Electronic Payments Network for patterns of abuse. EPN and the Fed operate the two ACH networks.

George F. Thomas, an executive vice president at The Clearing House, said the service is designed to catch transactions below the limits that would trigger other types of security alerts. For example, it would monitor the "receive accounts" of third parties for suspicious patterns, such as multiple debits originated each month against a single account.

That type of fraud can quietly add up, Mr. Thomas said. In one case, criminals stole $435,000 from a New York securities firm over the course of 18 months by repeatedly debiting an account for relatively small amounts. In another example, criminals used a third-party processor to initiate more than 10,000 debits, each for $137, from two banking companies. He would not name the companies involved.

EPN's service will maintain a "watch list" to warn other banks of originators that have been blackballed from the ACH network by one bank.

Roy DeCicco, a vice president at JPMorgan Chase & Co. and its industry issues executive for treasury services, said the industry must strengthen its fraud-fighting abilities in ACH and other payment channels. "The Fed tool is one tool in that process."

JPMorgan Chase, the nation's largest originating depository financial institution, has long incorporated risk caps and controls in its internal systems, Mr. DeCicco said, and the Fed service would help bridge the "risk gap" that forms when banks give originators direct access to the ACH network.

"We don't allow originators direct access," he said. "Some banks do. This tool is going to help those kinds of ODFIs."

Michael Bellacosa, a vice president at Bank of New York Co. and its head of global payments product management, said it has also stayed away from granting third parties direct access to the network. "It's not a business we're comfortable doing."

Complying with "know your customer" requirements can be problematic, even if the bank is comfortable with its third-party originators, he said. "You still need to go the step beyond that, to know the customers of your customer."

Aaron McPherson, the research manager of payments at Financial Insights, said that the increasing ACH volume, and the availability of different payment formats such as WEB and TEL, makes the system "more useful, but it also raises the risks."

Banks should adopt risk scoring models for ACH payments, such as those used for credit card transactions, Mr. McPherson said.

He applauded the new initiatives but warned that criminals blocked from one banking channel will continue to probe the financial system for weaknesses.

BITS, the technology arm of the Financial Services Roundtable, is working on a project to identify "cross-channel payments risk."

Gary S. Roboff, a senior consultant to BITS, said fraud risks are proliferating because payment systems designed to perform one kind of function now often duplicate the capabilities of other systems.

ACH, for example, was designed to execute repeating payments - such as payroll direct deposit or automated debits for insurance payments - between known parties, he said. Today, however, Web sites and telemarketers can use the ACH network to make "spontaneous transactions, initiated on the spur of the moment, with a party with whom he has had no prior relationship."

The analytical models that credit cards use to spot anomalous transactions are becoming increasingly important for the ACH system, he said. "Silos that used to be hermetically sealed - now they're porous."