Community banks are finding it extremely difficult to check out of the 18-month-old Troubled Asset Relief Program.

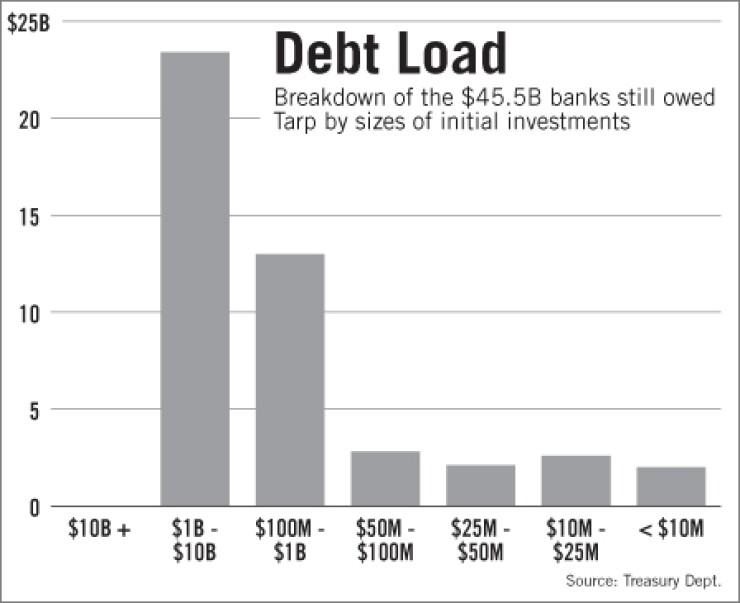

While all of the big banks have repurchased or converted preferred stock, and two-thirds of the regionals have followed suit, community banks are expected to hold the vast majority of unpaid Tarp funds on their balance sheets by the program's two-year anniversary.

Considering these perhaps unintended results, questions are mounting about whether injecting capital into the smaller banks was a good idea since it has done little to boost lending and could cost these institutions dearly in the long run.

"Given the difficulty of getting out, I am sure there are a lot of bankers asking themselves, 'Why did I take it?' " said Blake Howells, the director of research at Becker Capital Management in Portland, Ore.

D. Anthony Plath, finance professor at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, put it more blunty: "All we've done is created a bunch of zombie banks. It's not humane to those banks to give them false hope for survival."

The smaller the bank, the more likely it is still in the program. Roughly 81% of the banks that received $50 million to $1 billion in Tarp funds remain in the program, according to recent Treasury Department statistics. The number jumps as high as 97% for banking companies that received $10 million or less.

For now, bigger banks still owe a majority of the remaining Tarp funds, though their portion fell to 51% of the investment at May 18, from more than 87% at the program's height, the Treasury data says. Only six banks have individual Tarp commitments exceeding $1 billion, and analysts expect many of those to repay by early 2011. For example, Kevin Kabat, Fifth Third Bancorp's chairman and chief executive, said during a conference last week hosted by Barclays Capital that he expects the Cincinnati company to repurchase its $3.4 billion in preferred stock later this year.

Executives at a number of community banks are reluctant to characterize the program as an outright yoke, though most acknowledge a desire to exit. Obstacles range from erratic capital markets to regulatory impediments, they said.

"It is a little harder for the smaller banks to raise capital," said Kirk Bailey, the chairman, president and CEO of Magna Bank in Memphis, which is paying its $13.8 million in Tarp funds in installments so it can use retained earnings rather than selling stock. Magna, which repaid $3.5 million in November and is looking at a similar payment "in the not-so-distant future," hopes to be out of Tarp completely in the next 12 to 15 months, he said.

Donald Mullineaux, a University of Kentucky finance professor, noted that for a small bank, selling common stock is very cost-prohibitive. He said the typical investment bank wanted a minimum offering of $50 million to $70 million, with fees of 6% to 8%. "For smaller institutions, that looks extremely expensive," he said.

Not to mention that a good window for selling shares narrowed recently. The KBW Bank Index has fallen nearly 16% since April 23.

Rusty Cloutier, the CEO of MidSouth Bancorp, said he sees the company's $20 million in Tarp money as both an "insurance policy" and a yoke. "We have the money sitting in the checking account, but I don't want to return it until everything is stable," he said. Cloutier is worried that bigger banks that have already exited still have an advantage as long as the public views them as "too big to fail."

Cloutier and others touted Tarp funds, with a 5% quarterly dividend over the first five years, as a cheap form of capital. Howells wondered if that was indeed the case. "Preferred dividends are paid after taxes," he said. "If you look at the cost on a pretax basis with a 35% tax rate, the cost of capital can be 7% or more."

For those leading small banks, it's a concern that Tarp funds have not spurred lending in the absence of demand. Many executives have been hoping that an economic recovery and increased lending would generate the retained earnings necessary to pay off the government.

"The initial reason was to promote lending," Bailey said. "In hindsight, the Tarp money has become defensive capital … and part of that is protection against something cataclysmic. Things are better, but we're not out of the woods yet."

Community banks need that capital in part because of the high concentration of worrisome commercial real estate loans on their balance sheets. CRE made up 41.5% of total loans for banks with less than $1 billion in assets at March 31, according to data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. In comparison, such loans make up only 17.4% of total loans for banks with more than $1 billion in assets.

Analysts said questions about the government's rationale will intensify as more small bank participants fail. Midwest Bank and Trust Co. became the latest example on May 18, when Illinois regulators closed the bank even though parent company Midwest Banc Holdings Inc. had received $89.4 million in Tarp funds in December 2008.

Some observers contend, however, that while Tarp has been unable to encourage lending, it has facilitated survival for hundreds of small banks, allowing them to live to lend another day. "From that perspective, I think the program has served its purpose for the most part," Howells said.

Then there's Tarp's role in building confidence.

"As a confidence play, a run on a community bank is a much smaller problem than a run on Citigroup or Bank of America," said Mullineaux. But, in hindsight, extending capital to small banks seemed necessary "to make the program play in a political arena," he said.