If an automated, leaderless "company" called the DAO – which has raised the equivalent of $154 million in the largest crowdfunding effort to date – lives up to the hype, it could transform the way firms are financed and governed.

There's just one problem: It's unclear whether what this thing is doing is legal.

The DAO, which stands for Decentralized Autonomous Organization, has no managers, no legal documents and no central server. Over the last two weeks it has raised the $154 million (and counting) from more than 11,000 people by swapping its own "DAO tokens" in exchange for the cryptocurrency known as ether.

-

Interest in smart contracts is growing, in part because of the promise of lower legal expenses. But the programmers of these self-enforcing, automated agreements will still need to consult with lawyers to translate the terms into code.

May 19 -

The ability to program value exchanges without risk of censorship, moderation or theft gives smart contracts a leg up in servicing users who lack a mainstream banking association.

March 30 -

In focusing on private blockchains, banks make the same mistake companies made in the nineties when they favored private information networks over the open protocols of the Internet.

March 9 -

A concept that predated bitcoin itself is becoming more than a thought exercise as blockchains explore ways to harness smart contracts for greater uses.

January 8

Code running on a distributed network of computers will be entrusted to invest the proceeds in projects approved by the DAO's (human) members. They're not called shareholders, but the DAO tokens they receive for their ether will entitle them to vote on proposals and receive rewards.

"It's taking the principle of the blockchain to the extreme," said Stephan Tual, chief operating officer of

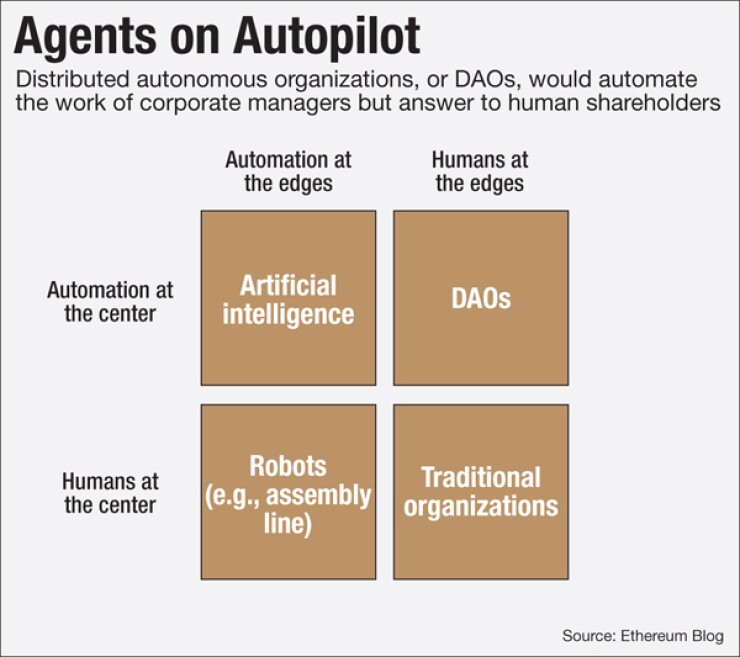

In theory, distributed autonomous organizations (of which the DAO is one of the first examples) are a hardcoded solution to the age-old

At a time when the financial services industry is trying to automate old processes to cut costs, errors and friction, DAOs represent perhaps the most extreme attempt to take people out of the picture.

"There's a lot of folly and fragility in human behavior," said Alex Tapscott, co-author of the book "Blockchain Revolution" and the CEO and founder of Northwest Passage Ventures, an advisory firm building early-stage blockchain companies. "How do you disengage this human behavior from processes and from decision making? What if we could automate much of that through self-executing smart contracts and autonomous agents?"

But many cryptocurrency observers are wondering if the DAO's crowd sale, which will end on May 28, is kosher under securities laws, since the DAO tokens in many ways resemble a stock.

The DAO is "operating at the boundaries of what is legal," said Emin Gun Sirer, associate professor at Cornell University and co-director of the Initiative for Cryptocurrencies and Smart Contracts. "Certainly the DAO does not have the protection that the law gives corporations" as we have come to understand them.

Preston Byrne, chief operating officer and general counsel of Eris Industries, was less equivocal. Selling tokens or crypto-equities as investments over the Internet to raise funds from unaccredited investors is against the law, he wrote in a

"Not maybe against the law, not possibly against the law, but straight-up, 100%, beyond-a-shadow-of-a-doubt against the law."

The DAO's

But "these projects are not necessarily investments," Tual said. They could be products and services delivered to the DAO's members, for example.

A disclaimer on the DAO's explanation of terms says the tokens do not constitute equity ownership in any public or private company or corporation. Their holders can use them only as the smart contract code allows within the organization.

"I'm very comfortable what we're doing is by the book," Tual said.

Carol Van Cleef, a partner and member of the financial services and banking practice at Manatt, Phelps & Phillips, said it's debatable whether the tokens constitute securities. If they do, who is the issuer? "Maybe it's not a security. It may be we're on the verge of some new law," she said.

The DAO is pushing the limits of understanding what a security is and who and what securities laws protect, Van Cleef said, and courts have demonstrated great flexibility in evaluating whether something is a security.

To claim there are securities involved in this organization is easier said than done, according to Marco Santori, who leads the digital currency and blockchain team at Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman and is a partner in its corporate and securities technology practice. Individually holding any of the participants in the DAO liable for potential losses would be a reach for regulators, he said.

"It's easy to think everyone involved in the DAO should be held liable for the sale of unregistered securities to unaccredited individuals but quite another thing to make that case stick, from a practical perspective," Santori said.

From a policy perspective, he pointed out that most people involved are just software developers and that it would take "a whole lot of lawyering" to show they're selling securities. "That's just bad policy, to hold software developers liable," he said.

What if bugs turn up in code and trap the members' funds? It's unclear who would be liable, Van Cleef said. "If something goes wrong in the corporation and the corporation loses money, people don't turn and sue all the shareholders."

Santori acknowledged that while there could certainly be a lot of losses and personal bankruptcies, and that those involved in the DAO could be held liable for selling unregistered securities, he said they probably won't be.

"Personally I think it's too important a development in corporate finance to hold anyone liable just yet," he said. It's more likely that the DAO fails as an experiment and all involved lose their investment. More important, he said, it has presented an opportunity to re-examine first principles on what is good corporate fundraising policy from regulatory and commercial perspectives.

Washington has already shown some open-mindedness. In October the Securities and Exchange Commission approved regulations allowing business owners to raise up to $1 million per year through online crowdfunding platforms. The rule requires sites like Indiegogo and Kickstarter to register with the SEC and implement measures to reduce the chance of fraud.

So far, the SEC and other regulators have gone after the low-hanging fruit in the blockchain space, but Santori noted they haven't made very difficult enforcements, showing caution, restraint and an effort to understand each participant's role.

Sirer agreed, saying that regulators are out of their depth when it comes to the blockchain industry, but that at the federal level they're not jumping at the chance to regulate its companies.

"They have chosen to follow a path with digital currencies that is incredibly permissive and accommodating," he said. "With the DAO we will see the same pattern. They're taking a wait-and-see attitude."

Santori said the DAO is just the next demonstration of what blockchains do: disintermediate unnecessary parties.

"We saw it with money and now we're seeing it with finance," he said, adding that blockchain technology eliminates the need for people and processes involved in forming a venture fund. "From a policy and law perspective, I think it's incredible how many people the DAO is showing us we just don't need."