-

The California company has poached lenders from larger rivals, while expanding into specialty finance lines. Those moves have positioned Opus for a growth spurt that should outpace organic growth at most other community banks.

March 3 -

Opus Bank in Irvine, Calif., has signed a lease to open its first banking office in Oregon.

November 6 -

Small business investment companies offer bigger returns than traditional loans, along with the opportunity for new business relationships and even CRA credit. Now banks are rediscovering this SBA program as a way to make equity investments in startups, while avoiding the Volcker Rule vortex.

April 28

Since opening its doors in September 2010, Opus Bank in Irvine, Calif., has grown from a few hundred million in assets to $5.8 billion. For most of that span its executives never gave any thought to the Small Business Investment Company program.

But it had a problem.

Opus operates a merchant banking division that focuses on lending to middle-market companies as well as arranging private-equity investments, and executives started to realize they needed even more tools to serve their customers.

"Situations kept coming up where our clients needed solutions beyond senior debt," Chairman and Chief Executive Stephen H. Gordon said in an interview Monday.

And, said Dale L. Cheney, head of Opus' merchant banking division, "it's very hard to find $2 million to $10 million of equity in the marketplace."

Then, like an increasing number of banks in recent years, Opus hit on the SBIC option offered by the Small Business Administration.

Under the program, investors organize funds which are certified by the SBA. The funds can leverage their privately raised capital by borrowing at a discounted rate from the SBA (about 2.52% lately), but they must invest in small businesses — defined as firms with tangible net worth below $18 million as well as average earnings below $6.5 million in the two years prior to receiving SBIC assistance.

In August Opus received a "green light" letter from the SBA allowing it to move forward with a plan to organize an equities fund.

"The establishment of a bank-sponsored SBIC is a meaningful differentiator that will enable Opus…to further address a company's capital needs by committing equity," Gordon said in a press release at the time.

Opus is the latest bank to ride the wave of interest in the SBIC program that has been building since the so-called Volcker Rule took effect in April 2014. The regulation placed strict limits on bank investments in private-equity funds, but it specifically exempted SBICs from its coverage.

As a result, the program "has grown dramatically since the [Volcker Rule] firewall was implemented," said Brett Palmer, president of the Washington-based Small Business Investor Alliance, a trade group representing SBICs. "Before Dodd-Frank, this was a space that was starved for capital." The Volcker Rule is part of the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act.

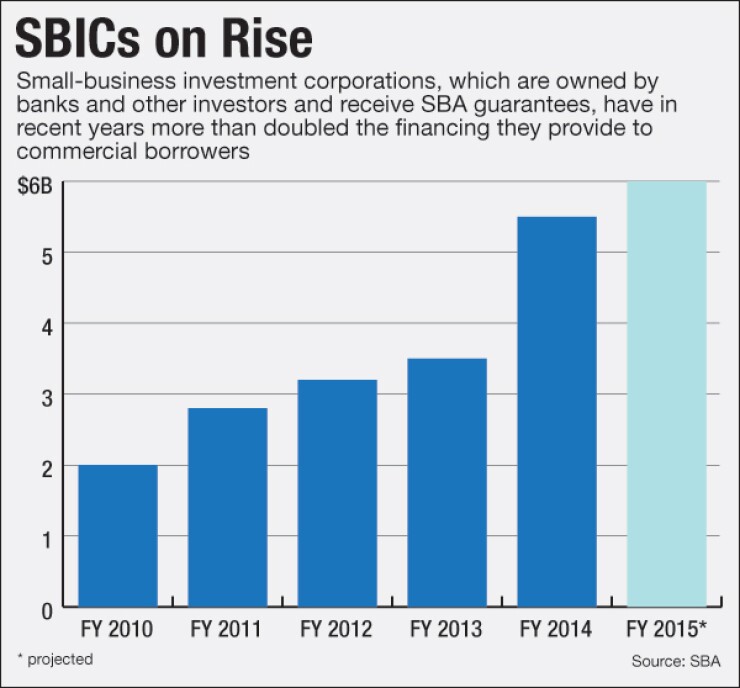

SBIC financing to small businesses jumped from $2 billion in fiscal 2010 to $5.5 billion in fiscal 14. It is expected to top $6 billion for fiscal 2015, which ended Thursday, according to SBA associate administrator Javier Saade.

(The SBIC program is less well known than SBA's flagship 7(a) program, which also enjoyed a record fiscal year. Through Sept. 26 it had guaranteed loans totaling $23.1 billion. The total for fiscal 2014 was $19 billion.)

Saade, who touted SBICs as a "compelling alternative for banks" in a speech to bankers earlier this year, noted that in addition to being the only overt exemption from the Volcker Rule restrictions on equity investments, participation in the program earns banks Community Reinvestment Act credit.

"We want more banks to participate," Saade said in an interview last month.

While Gordon acknowledged the importance of CRA credits, he said an SBIC would allow Opus to strengthen its ties with its borrowers. "These are meaningful relationships, so it's important that the client doesn't need to look outside for equity."

Opus does not yet have a timetable or target size for the fund. Its next task is to raise money. The company will stake some of its own cash and look to neighboring banks to provide the rest.

"We're specifically targeting banks," Cheney said Tuesday. "We have a lot of relationships up and down the West Coast. We want our investors to be our brethren."

Small banks have been a mainstay of the Small Business Administration's SBIC program since it was created in 1958, so in that respect, Opus's involvement represents no departure from the norm. Most, however, limited participation to investing. Few have chosen to step out front and manage a fund, as Opus seeks to do.

Of the approximately 300 SBICs currently operating, 44 are either bank-managed or do no borrowing from the SBA. The list of banking companies with SBICs includes Bank of America, Morgan Stanley, BB&T, TD Bank and Zions Bancorp.

Like most banks with SBICs , Opus intends to forgo borrowing from the SBA and operate a nonleveraged fund.

Among bank-sponsored SBICs, only one was established by a bank similar in size to Opus: 1st Source Capital Corp., whose corporate parent is the $5 billion-asset 1st Source Corp. in South Bend, Ind.

Michael B. Staebler, a Detroit-based attorney with Pepper Hamilton LLP, said he is representing another community bank that has begun the process of organizing an SBIC and he expects more to follow.

"There are a lot more people in the industry with entrepreneurial backgrounds," he said.

Certainly, Gordon and Cheney fit that description. Before organizing an investor group that recapitalized Bay Cities National Bank with a $424 million investment, rechristening it Opus Bank, Gordon founded Commercial Capital Bancorp in Irvine and built it into a $5.5 billion institution before selling it to Washington Mutual for about $983 million in 2006. He ran a hedge fund and was an investment banker and partner at Sandler O'Neill. Cheney, too, has a long background in investment banking, including as an investment banker at Goldman Sachs.

Staebler, who has assisted in the formation of more than 245 SBICs during his career, said banks that are eyeing SBICs today are especially interested in financial technology.

"There's great interest by banks in being able to troll around in the early-stage financial technology space," he said. "They're interested in finding a window into that field."