-

The Fed on Thursday issued proposals that would raise banks' minimum capital requirement to 7%.

June 7 -

Community bank Investors Bancorp Inc. agreed to acquire Piraeus Bank S.A.'s Marathon Banking Corp. unit for $135 million in cash, a move that doubles its presence in New York.

June 15 -

ViewPoint Bank in Plano, Tex., is selling its home lending unit to a Dallas-based nonbank lender as part of its continued shift from a thrift to a commercial bank.

June 8 -

Sterling Savings Bank in Spokane, Wash., is dropping the "Savings" from its name to reflect its transition from a traditional thrift to commercial-oriented bank.

February 7

Maybe George Bailey should've jumped — and made his savings and loan a commercial bank.

If he had, he'd have been much better prepared for the Federal Reserve's recent decision to raise certain capital requirements, a move some are calling the death knell for the classic thrift business model: lend to home buyers like crazy.

"We believe that regulatory changes following the financial crisis … have ended the viability of the thrift industry," analysts at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods wrote last week. "Higher capital requirements will not support the revitalization of the thrift industry, in our opinion, and as a result the industry will continue to fade away."

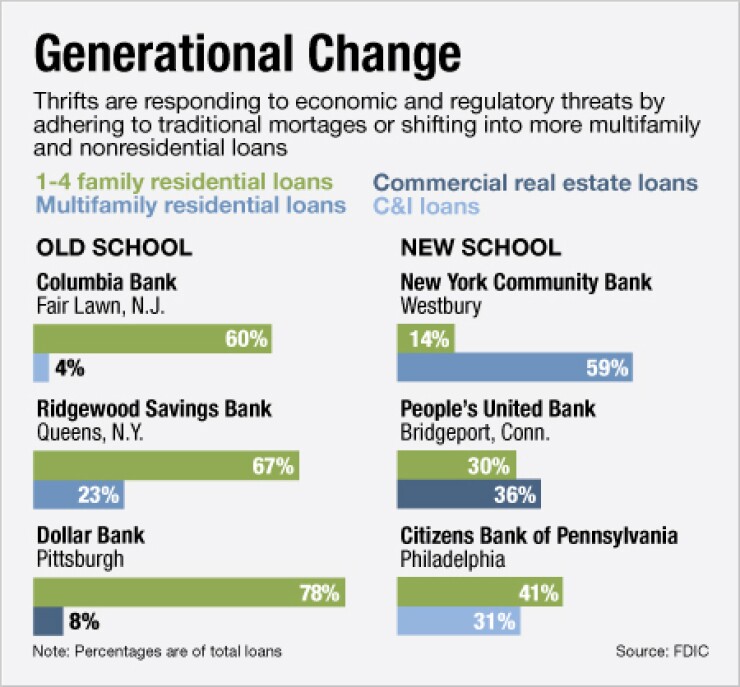

Thrifts have historically focused on residential loans, pretty much to the exclusion of all else. Maintaining high leverage allowed thrifts to post profits in spite of low margins and negligible fee income, said Frederick Cannon, Keefe Bruyette's chief equity strategist.

No longer. With residential real estate values battered by recession, such mortgages are now a higher-risk asset class, and many thrifts are dramatically reducing their dependence on home loans, in favor of different revenue streams.

In 2006, for example, the median ratio of residential mortgages to total loans at the 20 biggest thrifts was 78%. At March 31 of this year that ratio stood at just 61%, according to KBW.

The trend is likely to continue. The Fed's decision to adopt international capital standards promulgated by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision will push even more thrifts to abandon the old thrift model, Cannon says. Banks have until 2019 to comply with the Fed's new capital requirement.

The declines are apparent at some of the biggest thrifts.

Flagstar Bancorp in Troy, Mich., reduced its ratio of residential mortgages to 72% at March 31, from 90% in 2006.

At Investors Bancorp the ratio fell to 58% at the end of the first quarter, down from 90% in 2006. The $11 billion-asset Short Hills, N.J., company on Monday said it

A number of small thrifts, meanwhile, have abandoned their old ways by scrapping their thrift charters, getting out of the residential mortgage business, or both. ViewPoint Financial Group, a $3.5 billion-asset banking company in Plano, Texas, earlier this month agreed to

The $9.5 billion-asset Sterling Financial in Spokane, Wash., became a commercial bank in 2005 and has since reduced its exposure to single-family mortgages. The company in February dropped "Savings" from the name of unit Sterling Bank, severing any ties to its days as a thrift.

And Greene County Bancorp retains a savings association bank charter, but it has operated more like a commercial bank since the late 1990s, said Don Gibson, the Catskill, N.Y., company's president and chief executive. While one- to four-family residential loans still make up about 71% of the $579 million-asset company's loan book, Greene County has been putting more emphasis on its commercial lending, he said.

"Everyone has to find their niche, and the traditional thrift model doesn't work well for us," Gibson admitted. "Just because you're chartered as a thrift doesn't mean you are a thrift."

Some savings and loans are digging in their heels.

"A lot of our peers have moved in the direction of being a commercial bank," said Peter Boger, the chairman, president and chief executive of Ridgewood Savings Bank in Queens. "I don't see that happening anytime soon here."

Boger's $4.8 billion-asset institution is the largest mutual thrift in New York. "The thrift is alive and well at Ridgewood," he said.

Douglas Faucette, a banking lawyer at Locke Lord, said many smaller thrifts have stuck to their guns and continue to focus on one- to-four-family residential real estate loans. And the stricter capital standards won't cause these small thrifts to blink an eye, he said.

"If you look at the financials of community thrifts, they could care less about Basel," Faucette said. "The whole concept of additional and supplemental capital is foreign to them. They've always been overcapitalized."

Ridgewood, which has more than two-thirds of its loan book in the first quarter in one- to four-family residential loans, already surpasses the Basel capital requirement, Boger says. At March 31, Ridgewood posted a total risk-based capital ratio of 23.8% and a leverage ratio of 12.2%.