The political world has had one big idea on banker pay: make top executives eat more of the losses when things go wrong. While the idea has some virtue in relation to the CEOs of too-big-to-fail banks and investment bankers, it has been oversold as a cure for banking compensation more generally. While C-level executives are certainly answerable to shareholders, they must also be attuned to the bank's tail risk, or solvency — which is a chief concern of debtholders.

More important, the compensation of line-level employees has been largely missing from the recent discussion around incentive compensation. Any plan to align compensation with risk should embrace all the risk-takers in the bank. Front-line staff and their managers shape much of the risk within a bank, though because they are only responsible for the bank's solvency in the aggregate, their individual incentives may be more aligned with those of shareholders. Front-line staff cannot afford to have a significant portion of their pay delayed, nor will their incentives be aligned with the interests of shareholders by token amounts of stock. Banks that overemphasize mechanisms such as restricted stock and deferred compensation may not be able to keep talented staff long enough to achieve their aim of aligning incentives with stakeholder interests.

This is particularly true for many lending businesses, where the gap between making a loan and the bank realizing a loss is long and uncertain. Even if one could lock pay in a box for five years, it would not be possible to do the same for other rewards that bankers compete for such as the capital to grow a business and the influence that comes with a promotion.

So what is the answer? In addition to restricted stock and clawbacks for top executives, the bank needs to bring forward the economic cost of risk so that it can better decide who and what is a success — and align all risk-taker rewards with the bank's stated risk appetite.

True, some banks already risk-adjust the size of general bonus pools. But this is not the same as risk-adjusting compensation to reflect the decisions of individual lenders. Worse still, risk-adjusted compensation is typically calculated without any formal reference to the bank's risk appetite.

To take risk appetite into account, the bank must first set out its board-approved risk appetite using an objective dollar-risk metric. The aim should be to capture both expectations about long-term average losses and potential tail-risk losses, and then allocate these down to the level of business units.

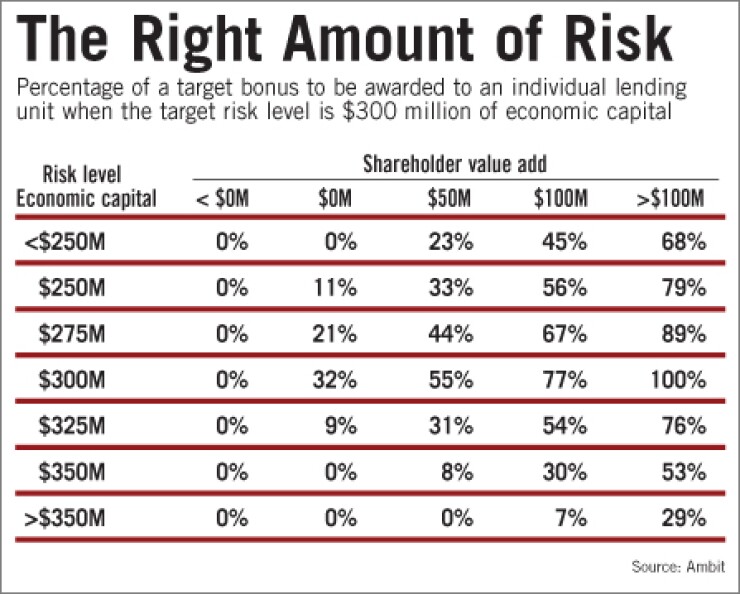

Setting risk appetites in this way is work in progress across the industry, but once they do this, banks will be able to adjust lender compensation in the way shown in the chart here.

In the chart, a matrix sets out the percentage of a given target bonus that will be awarded to a local lending unit. The percentage is determined in part by a calculation of their contribution to risk-adjusted shareholder value added. It is important to note that the lender's bonus is not a simple function of the creation of more risk-adjusted profit. Instead, the matrix is also sensitive to the risk-appetite limits of the bank expressed in terms of economic capital (vertical column). When the lender exceeds the "soft" economic capital amount that has been allocated to the unit, they begin to lose rather than gain bonus money.

The bank will also want to set "hard" economic capital limits and notional limits above this point — risk-adjusted compensation will support, not replace, risk controls.

Conversely, the matrix can also be constructed so that lenders can't maximize their bonus potential unless they use up most of their economic capital allocation, i.e., take enough risk of the right kind. The big objection to the approach presented here is that it depends on an estimate of risk and risk costs. Didn't banks just make a few major mistakes in estimating their tail risks?

They may have — and the pressure is indeed on banks to improve their risk modeling — yet the larger reason is likely that these risks were understood, but not made visible through management reporting or made relevant through incentive compensation.

Shahram Elghanayan is a managing director and Kaizad Cama is a senior consultant at SunGard Ambit Risk Consulting.