Want unlimited access to top ideas and insights?

Regulators are quietly warning banks that the overly aggressive pursuit of brokered and other high-priced deposits to fuel loan growth poses a long-term threat to liquidity.

As the deposit wars heat up, many banks want to make sure they have enough deposits to support loan demand. Banks are

Since the first quarter of 2015, brokered deposits have increased from 6.57% of total industry deposits to 7.23% at Dec. 31, according to BankRegData.com.

Regulators are sympathetic to banks’ challenge in retaining core deposits in a rising-rate environment, but they have recently raised caution flags about becoming too reliant on brokered or promotion-driven deposits that could quickly flee to the highest bidder or move elsewhere if the U.S. economy begins to cool, according to bankers and professionals who do business with banks.

“Regulators are saying, make sure you have some liquidity available” in a pinch, said Joshua Siegel, CEO of StoneCastle Financial, which provides deposit services to community banks.

To be certain, the large majority of banks still retain plenty of liquidity. Megabanks and large regional banks also should be able to withstand a huge surge of withdrawal demands. But some midsize and community banks that already struggle to find enough deposits to meet loan growth needs could find themselves vulnerable.

David Bishop, an analyst at FIG Partners, described a theoretical example of how a bank could get into liquidity trouble, especially if it has a high loan-to-deposit ratio, in the 120% to 130% range. If this bank promotes a one-year certificate of deposit with a 3% interest rate, the bank will bring in a lot of new deposits. If the bank puts those new deposits into 30-year mortgages, it may not have the cash available to meet withdrawal demands in 12 months when the promotional CD expires.

Regulators are “worried about short-term liquidity and they want boards to adopt policies” on minimum requirements of liquid assets (cash and securities that can be sold quickly) of at least 10% of total assets, Bishop said. That is higher than the traditional preference of 8%, he said.

Bishop declined to identify the banks where executives told him of the regulators’ concerns, but he said that both federal and state bank examiners have issued the warnings.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and the Federal Reserve Board declined to comment for this story.

This new situation contrasts with the conditions of the past decade, when the industry was awash in deposits as the Fed kept interest rates near zero. Now that the Fed has raised rates, consumers are willing to pull money out of banks in search of better rates.

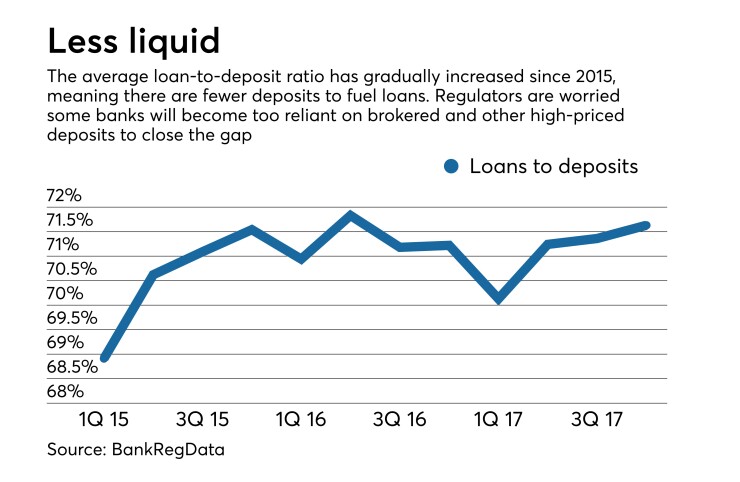

Overall industry trends show that liquidity has already started tightening, albeit on a gradual basis. The industry’s average loan-to-deposit ratio has gradually increased since the first quarter of 2015, climbing 272 basis points to 71.63% at Dec. 31. That means there are fewer deposits to fuel loan demand.

The best way for banks that have high loan-to-deposit ratios to manage liquidity is by seeking funds from a diversity of sources, said Brian Canina, chief financial officer at the $2.4 billion-asset PeoplesBank in Holyoke, Mass.

PeoplesBank has a loan-to-deposit ratio of 108%, which is higher than the industry average. But the mutual bank can meet its liquidity needs because it manages its securities portfolio to hold a large portion of liquid assets, and it funds loans from wholesale deposits and Federal Home Loan bank advances, in addition to retail deposits, Canina said.

“We are constantly monitoring our liquidity position and we are constantly looking for new sources of liquidity,” he said.

Still, regulators remain concerned that some banks rely too heavily on wholesale funding to fuel loan growth,

“Regulators are trying to stem the tide on that,” Dohren said. “Regulators don’t like wholesale funding, because if your bank has capital issues, the wholesale funding valve gets turned off.”

Instead of loading up on brokered deposits, banks should stress diversification to help defend against a potential liquidity crunch, Siegel said.

“You want diversity in the maturity of deposits, diversity by provider, diversity by market and by deposit type, both consumer and commercial deposits,” he said. “You want diversification so you don’t have a morning when you wake up and you have an overconcentration in a specific area.”