Eighteen years ago, global financial markets awoke from years of yield-seeking slumber to news that BNP Paribas had halted withdrawals from three of its investment funds. The systemically important French bank had concluded "it couldn't 'fairly' value" the U.S.

Ask anyone today about the cause of the global financial crisis and most would correctly point to poorly underwritten subprime lending on a mass scale. Some may mention the credit default swaps that would, theoretically, help investors in the loans insure themselves against loss, or the aggressive securitization practices which paved the way for products like CDO-squared. Few, however, would likely point to the thin veneer of capital held by the world's largest financial institutions — identified after the crisis as global systemically important banks, or GSIBs — that was a real catalyst for the near collapse of the financial system.

Few of us in the financial markets at the time, or among the American public, were unscathed by the global financial crisis. We all hoped our industry had learned its lessons on hidden leverage and capital adequacy and would not forget the mistakes of the past. Alas, it now seems that bank and financial market regulators are indeed ready to forget certain of those lessons and unwind some of the key regulatory protections created in the wake of the crisis.

The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve, for one, has shown signs of this global financial crisis amnesia. On June 27, the Fed, by a 5-2 vote,

The majority in this Fed vote reasoned that in 2025, the need for the eSLR as a "backstop" for risk-based capital requirements is less important, because it is constraining bank lending. They also believe that by reducing the eSLR protections, the proposal would give U.S. GSIBs greater leeway to buy, sell and trade more of the increasing supply of U.S. Treasury securities.

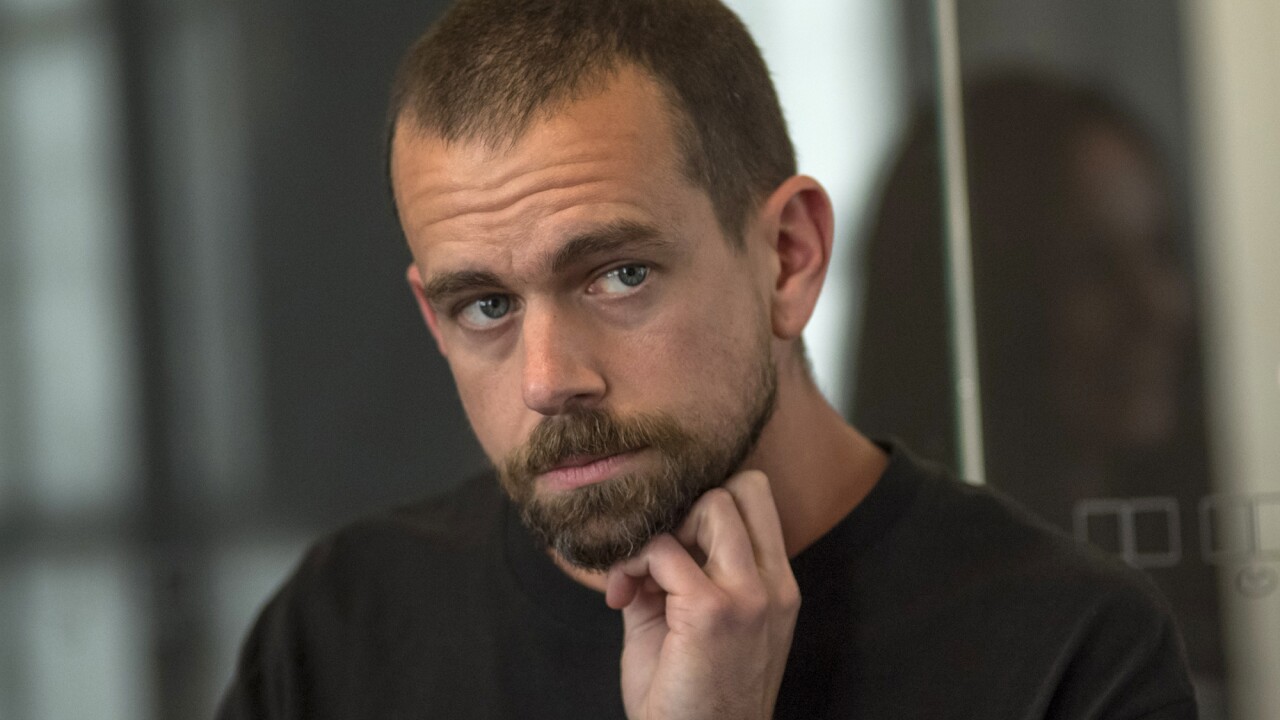

Federal Reserve Vice Chair for Supervision Michelle Bowman said she wants banks to be competitive in the digital assets space, provided those operations are siloed from the traditional finance side of the business.

By the Fed's own estimates, though, the lower eSLR would reduce aggregate Tier 1 capital at these GSIB's depository subsidiaries by $210 billion.

We should also appreciate that a key value of the eSLR is one not inherent in other types of capital requirements. That is, it captures and considers the magnitude and leverage from off-balance sheet assets while supporting greater transparency of impairment to a bank's capital base. This is consistent with the Fed's

Finally, note that the eSLR also considers all types of financial assets on an equal basis. Whereas risk-based capital rules encourage banks to invest in lower-risk assets like U.S. Treasury securities or Treasury-backed repurchase agreements, the eSLR rebalances these investment incentives to enhance the risk/return profile of private-sector lending. While risk-based structures are good for the Treasury market, their redirection of investment capital away from the productive side of the economy in favor of the sovereign will impede future economic growth.

Nearly two decades ago, the world faced a financial abyss when a toxic combination of bad policy, faulty lending, and the complicated and interconnected securitization practices infected an unprepared financial sector teetering on a foundation of deficient capital. It took most of the 2010s to right these errors and create a more financially sound and operationally prudent banking sector.

Now is not the time to forget the hard lessons learned from this not-so-distant past. One of the most important lessons is assuredly that GSIB capital adequacy must be robust and take precedence. The contrasting objectives of this current Federal Reserve Board proposal on eSLR seem to ignore that lesson, trading global financial crisis capital adequacy protections for enhancements to U.S. bond market liquidity. Cutting the eSLR to foster U.S. Treasury demand is systemically risky business.