A growing number of states have either enacted laws limiting fees for gift cards or are considering them, potentially eroding issuers' business case for the popular cards.

For retailers, one of the key benefits of gift cards has always been that they can debit from the cards the costs associated with maintaining inactive accounts. Or retailers may simply claim a tiny balance of, for example, 86 cents, left over by the cardholder for a year or more as abandoned property to get the account off the books.

It's an attractive proposition for retailers, as they are assured the full value of the card will accrue to them regardless of whether the value is spent in their stores. Nor do retailers have to worry that the cost of maintaining an inactive account eventually will exceed the amount of the remaining balance.

But retailers and third-party processors that offer gift cards can no longer take that for granted. A recent movement among states is producing a flurry of laws and pending legislation seeking to prohibit gift card issuers from claiming unused funds on a card or assessing maintenance fees on inactive accounts.

At the moment, six states have laws on the books prohibiting fees on inactive gift card accounts and another 18 have bills pending, according to the Washington D.C.-based National Retail Federation. California, Connecticut, Massachusetts and New Hampshire are among those that have escheat laws banning gift card issuers from claiming unused balances on cards after a year or more of inactivity. In these states, issuers are required to deposit unused balances into a state-run account where the balance will remain until the cardholder claims it or it is the seized by the state as abandoned property. Beyond that, another 68 bills addressing inactivity fees, escheat or both, reportedly have been introduced in all 50 states.

"There is definitely a movement afoot among the states to enact legislation pertaining to these issues and it is beginning to cause some headaches for retailers," says Mallory Duncan, general counsel for the NRF. "Anytime a retailer is required by law to carry an expense that was unexpected, it can have a negative impact on their operating costs."

Unspent Money

How severe the impact will be is difficult to say since the laws pertaining to escheat and inactivity fees on gift cards are so new. What is known, however, is that the pot of unspent money on gift cards probably exceeds $5 billion. Some 12% to 14% of the value of gifts cards sold in 2003 went unused, according to figures from TowerGroup, a Needham, Mass.-based market-research firm recently acquired by MasterCard International. Gift cards are one of the fastest growing payment card products in the market with an estimated volume in 2003 of $45 billion, up 50% from 2002. TowerGroup projects volume on gift cards will exceed $90 billion in 2007.

Granted, retailers get the float associated with prepayment of funds for gift cards without having to sell any merchandise, but they argue the cost of maintaining the account, which is about $1 a month on average, adds up quickly for merchants with large gift card portfolios. With no interchange earned on retailer-issued gift cards, account maintenance costs ultimately can exceed the face value of the card.

"There is a cost associated with running and maintaining these programs," says John Gould, director of consumer lending and bank cards at TowerGroup. "For retailers, it is insane for them to try and track down a cardholder with a balance of less than $10 so the cardholder will use it or reclaim it, let alone maintain that account indefinitely."

But pending legislation has some retailers and processors resigned to the fact they are better off to forgo claiming unused balances and inactivity fees now, rather than wait for more state laws to be enacted. The fear is that by waiting, they may be subject to class-action suits once laws regulating how they are to handle unused balances are passed.

"We don't share in any of the breakage or unused portion of gift cards out of concern it might leave us exposed to a retro class-action suit once legislation in this area is passed," says Aaron Sorgman, president and chief executive of TenderCard, a Falmouth, Mass.-based gift card processor. "More laws pertaining to gift cards will be coming. Any responsible processor or retailer is not going put themselves in a position to run afoul of the law."

What is expected to happen in the short-term is better disclosure from retailers about card fees.

"Merchants are getting better at explaining the terms and conditions associated with use of the gift cards and disclosing any fees," says Karen Larsen, vice president of marketing for ValuLink, an Englewood, Colo.-based gift card processor owned by First Data Corp.

Ultimately, though, industry experts predict legislators, retailers and processors will strike an accord on the fees they can charge for gift cards. That's what happened in the automated teller machine industry when banks started levying surcharges, some even on their own cardholders, for out-of-network transactions. Before legislators and banks reached a compromise on the issue, each bank could charge what it wanted. Today, consumers typically pay $1.50 to $2.00 to their bank and to the bank owning the ATM for making an out-of-network transaction. Consumers have accepted these fees as the cost for making such transactions.

"At some point all the parties involved are going to have to find a settling point where fairness about recouping the costs of maintaining gift card accounts is reached," predicts Sorgman. "It may mean consumers having to pay for the product."

That is already the case with general-purpose gift cards issued by American Express Co. and Visa and MasterCard banks. AmEx charges consumers $5.95 to purchase a gift card over its Web site and a $2 maintenance fee if the value on the card is not spent within 12 months of purchase.

Consumers have shown a willingness to pay these fees. AmEx says it is enjoying triple-digit growth rates for its Gift Cheque since its inception in 2002.

"Our card is more of a financial instrument and we try to educate legislators on that point," explains Randall Beard, senior vice president of global marketing and product management for AmEx. "There is a cost associated with the customer service behind the card."

Tiny Balances

What's driving cash-strapped states to enact gift card laws is a combination of seeking to claim revenues from abandoned property-which an unused gift card balance is considered-and consumer activism. A common argument is that retailers get use of the funds on a gift card before any merchandise is sold to the cardholder, which means merchants also get additional use of their inventory. The longer a card is inactive, the greater the float on the money for the retailer.

Trouble is that many of the balances left on gift cards are tiny. Up to 90% of the value of a gift card is redeemed in the first 60 days after issuance. After that point, 50% of the remaining value is never redeemed in most cases, according to payments experts. On a $100 gift, the issuer is left managing an account with a balance of $10 or less.

Given the cost of maintaining an account, a card with an unused balance of $10 or less becomes a money-losing proposition if the issuer cannot charge an inactivity fee. "Inactive fees are intended to close low-volume accounts," says Ariana-Michele Moore, an analyst with New York-based Celent Communications. "What's a retailer going to do with an account that has a balance of less than $1?"

Despite the push for legislation on gift card fees, processors and merchants insist the business case for retailer gift cards remains strong. Indeed, gift card holders tend to spend 30% more than the face value of the card on average, according to payments experts.

Other benefits include lower management costs compared to paper gift certificates, greater potential for impulse buys because cardholders are more apt to carry the card in their wallet and, of course, a low-cost form of advertising.

"There are still a lot of compelling benefits to gift cards even if retailers can't charge maintenance fees," says Bill Farris, director of emerging card products for Dallas-based merchant processor Paymentech LP. "I don't see the current legal environment as having turned merchants away from gift cards."

Still, the NRF and other merchant trade groups are actively lobbying to curb gift card legislation. The aim is to educate legislators about retailers' costs to maintain such accounts so that any proposed legislation is less restrictive. The NRF last month, after this issue of CCM went to press, was scheduled to hold a roundtable that included processors, retailers and legal experts to discuss the future of gift cards.

"Maintenance fees are designed to encourage cardholders to use the value on the card in a reasonable period of time," says the NRF's Duncan.

As with any card product, incremental sales determine how profitable the product is for a merchant to accept. With consumers demonstrating a clear penchant for spending significantly more than the face value of the card, right now it appears unlikely that state laws governing how retailers make use of unused funds on gift cards will derail the product.

"Consumers want gift cards, and that is reflected in sales of cards," says TenderCard's Sorgman, whose company saw a year-to-year increase of 300% in gift card sales over the past holiday season. "Legislation in this area is going to come, but there is evidence consumers will pay to get gift cards, which suggests there is room for a compromise."

Retailers hope any compromise will come on terms as favorable to them as possible.

-

Now that the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has refused to request funding from the Federal Reserve System, many experts see the case making its way to the Supreme Court.

November 27 -

The two regional banks, which are combining in a merger of equals, had previously said they expected to complete the deal sometime in the first quarter of 2026.

November 26 -

The bank is a step closer to having its own U.S. dollar-pegged cryptocurrency. It could become the first major financial institution to issue a stablecoin.

November 26 -

Recent high-profile ethics violations by senior Federal Reserve officials, including new revelations concerning stock trades by former Fed Gov. Adriana Kugler, have sparked debate over the effectiveness of the central bank's oversight, even as some observers stress such cases remain rare.

November 26 -

The Swedish financial technology firm issued its first stablecoin and signed a gift card distribution deal with BlackRock. Also, EMVCo is examining AI's impact on processing and more in the American Banker global payments and fintech roundup.

November 26 -

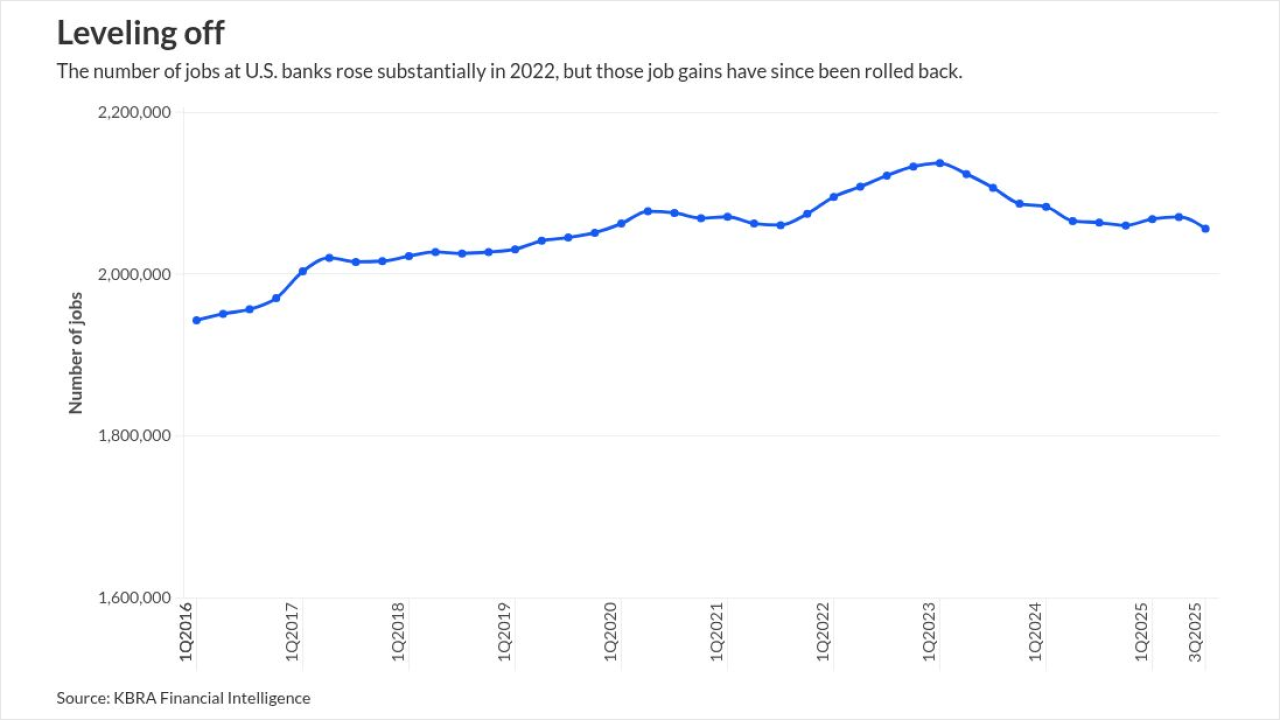

U.S. commercial banks and savings banks have reduced employment by nearly 81,000 since the first quarter of 2023, including a net loss of 7,463 positions during the third quarter of this year, according to a new report from KRBA Financial Intelligence. Big banks, which have been embracing artificial intelligence, were big contributors to the decline.

November 26