Even though the

Instead, it is far more likely that individual states will take up the spirit — and some of the particulars — of the European Union's sweeping legislation that has given European consumers far more control over who has their data, how they use it and how long they can store it.

Along the way, the payments industry will continue to provide key examples for others to follow in terms of what needs to be done to keep sensitive data safe, whether in storage or in transit.

"In the U.S., we tend to collect lots of everything, because we feel you never know when you are going to need it," said Scott Giordano, a privacy attorney and vice president of data protection at Spirion. "That is the exact opposite of GDPR, which says you don't collect anything you don't need. And if you want to use that data for something else not originally intended, you have to get permission from the consumer."

Talk of the European Union's advanced version of its European Data Protection Act had picked up steam as long as three years ago during initial GDPR planning, but it was in full force early last year when European companies and those in the U.S and other countries with European customers knew it was becoming law in May 2018. And the accompanying hefty fines for non-compliance put many companies on a fast track to having their data security house in order.

Over the first year, aspects of GDPR are trickling into state laws in the U.S., said Giordano, who calls himself "an evangelist for data protection" because his role with Spirion calls for educating customers on the data security and privacy technology to advance compliance.

The 72-hour breach notification of GDPR is migrating into state laws and many U.S. states are viewing data privacy and data security as one problem to be tackled at the same time with the same rules.

California established its own version of GDPR in July of 2018 with the

About 27% of U.S. companies are

"I don't think we will ever have a national policy," Giordano said. "That train may have left the station."

Because most everyone is interested in protecting data, it would be hard to envision any part of the U.S. indicating it would not want a data protection law, Giordano said, but it becomes a different discussion in the U.S. "because the people in Washington, D.C., can't agree on anything, thus making it a different discussion."

Still, in his work across the country, Giordano said as many as 12 to 15 states put together their own privacy initiatives last year, and just as many are establishing them this year. These states would follow California law, which stresses consumer control of data, or Ohio law, which focuses more on businesses getting cybersecurity matters in order.

"I completely agree with the position that the U.S. will wind up with a state-by-state approach to a GDPR equivalent versus a federal law," said Julie Conroy, research director and fraud expert at Aite Group. "First, Congress is too polarized right now to get much of anything done, especially something that requires bipartisan support."

In the U.S., any advancement of a GDPR type of protection will "wind up looking similar to what we have with data breach disclosure laws, where we have a patchwork of state laws, and multiple attempts to pass something at the federal level," Conroy said.

That approach will create challenges for compliance, Conroy added. "That may eventually be the motivation to get something done at the federal level, since this potentially could be very costly for businesses if there are substantial differences between the state laws."

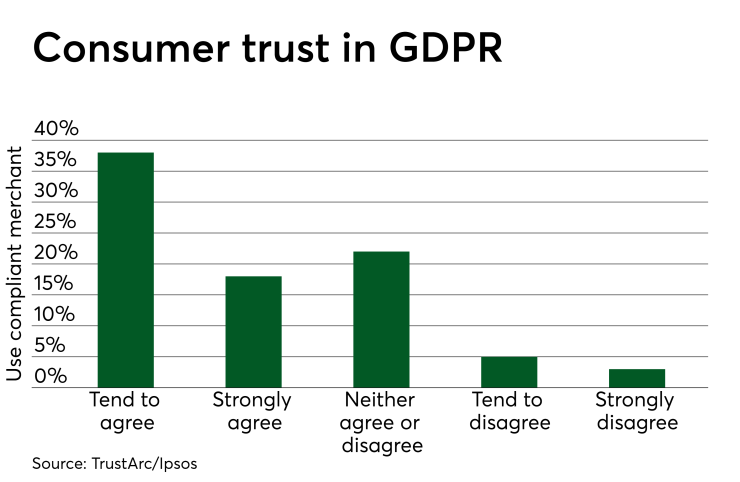

Anything that unfolds in the U.S. can point to growing consumer interest in Europe, with a May

The survey, conducted through Ipsos Mori of 2,230 adults ages 16 to 75, also revealed 56% of consumers would be more likely to do business with companies or organizations that had certification for being GDPR compliant.

In addition, in the first year of GDPR, 47% of consumers said they exercised their GDPR privacy rights by making a request related to their data to a company. Of those, 35% said they unsubscribed to email marketing; 23% did not provide consent to install cookies; 13% restricted use of personal data; 10% asked that personal data be deleted; and 5% requested access to their personal data.

Still, a fair number, 33%, admitted they were not confident they could tell if a company or organization is GDPR compliant.

A year into GDPR, some research indicates about half of the companies in Europe continue to

No matter how the data security rules continue to advance in Europe, or become established in the U.S., some of the payments industry's current rules and habits will carry weight.

Various aspects of the GDPR that find favor with complying companies have roots in payments security. One is the

"The idea of tokenization, which is PCI-DSS standard, is something the Europeans are in love with, and they call it 'pseudonymization,' " Giordano said. "It is the same idea, though tokenization is really confined to just the payments industry."

Tokenization replaces payment card numbers with unique characters to represent only a specific transaction when the data is being stored.

Other companies seeking GDPR compliance are seeking some version of tokenization, Giordano said. "And that is great news for all of us," he added.

Protecting payment credentials has always been vitally important, but the GDPR or any other law trying to emulate has to spread far beyond financial data.

"Credit cards are just a tiny piece of things, in terms of losing private data," Giordano said. "Think of your cellphone, and you have your entire life on those devices, and they are sharing information with so many parties that you have no idea about."

In that regard, and in a mobile commerce world, "your data is available to the rest of the planet," Giordano added.