In the computing world, username and password are inseparable. Rarely are the two ever apart, yet passwords lived in single existence for centuries, first cited in ancient times when Roman sentries would demand that a stranger offer a password or watchword before being allowed to pass.

It wasn’t until the 1960s at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) that the modern computer password was introduced. The university had developed a Compatible Time-Sharing System (CTS) to which all researchers had access. They were granted a certain amount of time on the computer and to monitor that time, they were required to login. Then, to help keep individual files private, Fernando Corbato, a prominent American Computer Scientist, created the idea to use passwords.

However, like many static fraud prevention solutions, they had a short life span. Soon after MIT began using them, they experienced the earliest documented theft of passwords. In the spring of 1962, one of MIT’s CTS users who wanted more time to run performance simulations, printed all of the passwords stored on the system and shared them among friends.

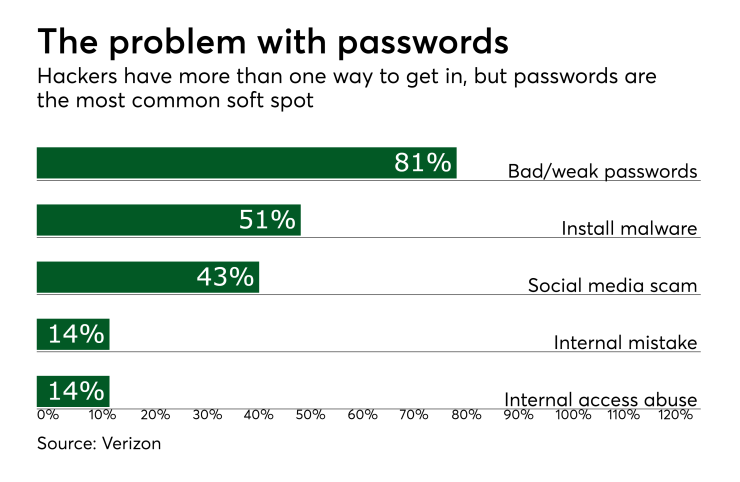

According to

Even though he invented the modern-day password, Fernando Corbató has admitted that managing lots of different passwords can be “a nuisance.”

“I don’t think anybody can possibly remember all the passwords that are issued or set up. That leaves people with two choices. Either you maintain a crib sheet, a mild no-no, or you use some sort of program as a password manager. Either one is a nuisance," he said.

While Corbató offers two good ways of coping, the truth is many people opt for a third, less-preferable choice—reusing the same password.

In their 2018 Psychology of Passwords eBook, LastPass survey results showed that: 91% of people interviewed knew that using the same password for multiple accounts is a security risk, yet 59% mostly or always use the same password; 53% of respondents said they haven’t changed their password in the last 12 months; 63% of millennials reuse the same password, citing the fear of forgetting; 47% of respondents said they use the same password for work and personal accounts.

Creating strong passwords might not be as difficult if every organization deployed the same policies and procedures. However, some websites require the use of numbers and letters; others look for symbols. Some expect a minimum number of characters; others impose limits. Some are case-sensitive; others not. A few validate the strength and complexity; others allow insecure passwords, like 12345.

Compounding the problem is that people often forget passwords, especially if they don’t use that account on a regular basis. While organizations have leveraged techniques to strengthen passwords, often the way to verify someone who has forgotten a password invokes even weaker security. A text message with a one-time code is sent or a challenge question is presented: “What’s the name of your first pet?”; “What is your favorite sports team?”; “What is your mother’s maiden name?” Anyone sufficiently motivated can often find these answers within the postings/friends/photos of an individual’s social media pages.

While some companies do a great job using passwords to protect their users, it is safe to say that additional security measures should be used to truly keep consumers accounts and data protected.

For businesses to protect their customers and stop account takeovers, while still providing a frictionless customer experience, new security approaches must be employed. It is critical that businesses strike a balance between security and convenience. Businesses must be able to confidently assess who they are interacting with—recognizing reliable, repeat customers as well as detecting suspicious account activity. At the same time, consumers of all ages and technological backgrounds must be able to easily interact with the organization’s site.

It is critical to use technology that operates behind the scenes, requiring no additional actions by valid customers. For example, some ways companies can evaluate login information beyond the credentials entered include: Was the username and password copied and pasted? What are some of the device attributes? Is it a mobile device? What is the language setting? What is the time zone? Is the customer known to the organisation? Are the actions typical or atypical?

Identity must be more than just a “username and password”—no matter how well those two words fit together.

Editor's note:

This is part one of a six-part series of articles describing the current state of digital identity and account takeovers. This article offers an evaluation of passwords, including their security applications today and expectations for the future.