-

Banks are increasingly competing with nonbanks to develop products for low-income and underserved customers. Here are the crucial questions they need to ask about regulation, technology and the competitive landscape.

June 4 -

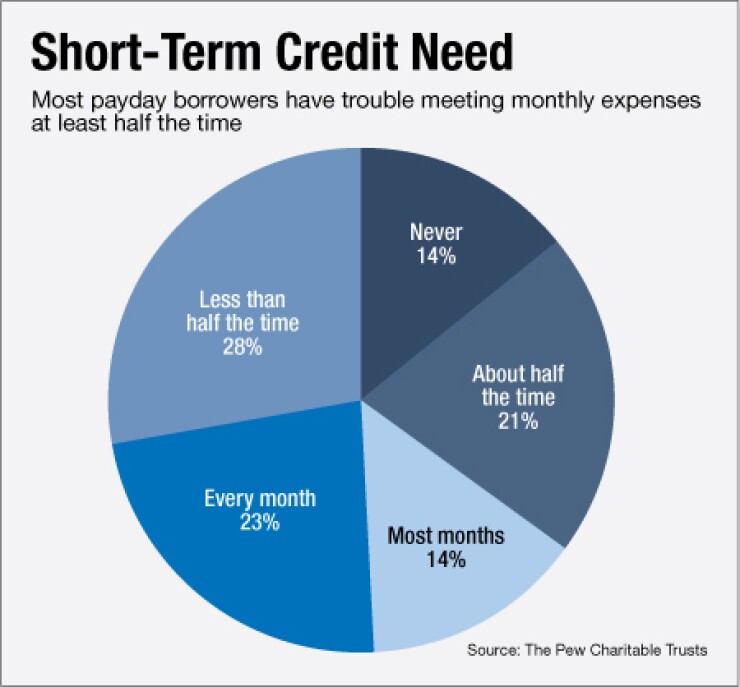

Facing strict new guidelines on deposit-advance loans, banks must now decide if it's worth their while to offer short-term credit to cash-strapped borrowers.

April 25 -

Raj Date, the former deputy director for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, has started a bank advisory firm that will focus on consumer finance issues, including assisting mergers and acquisitions through private equity partnerships.

April 17

Raj Date, the former deputy director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, wants to help banks build a better payday loan.

Date, who left the CFPB in January, on Thursday officially opened the doors of his consumer finance consulting firm, Fenway Summer. The company's first priority is mortgages, but Date said in an interview Thursday that he also wants to focus next on the

Developing a better short-term loan is "the single most promising thing" in the portion of the consumer financial industry that serves low-income and other financially underserved customers, Date said.

"It's a real thing, and it's a real need, and it is pretty inefficiently provided today," he says, adding that he wants to work with "one or more" banks to help them develop a better version of their so-called deposit advance short-term loans.

Date was speaking on the sidelines of the Underbanked Financial Services Forum, an annual conference devoted to banking and technology for low-income, young, immigrants or other financially underserved people. (The conference is co-sponsored by American Banker and the nonprofit Center for Financial Services Innovation.)

He is picking a difficult but potentially opportune time to focus on short-term credit products as banks try to figure out how to best serve cash-strapped customers without angering consumer groups and running afoul of regulators. Regulators have introduced strict guidelines that some expect to

Consumer advocates have

Date sees what he calls "the small-dollar credit problem" as one that can be largely solved by better data, which can then give lenders an incentive to lower their prices. Banks, with their sophisticated and established operating systems, have the means to offer cheaper short-term loans and still make a profit but they have to be willing to significantly rethink the prices they charge, he says.

"The credit costs are much higher than what they need to be. I think that through the application of more and different data sources, you can actually make fraud and credit decisions much better than has been possible in the past, and that, with the right competitive dynamic, can therefore start bringing pricing in," he says. "The deposit advance product should, just logically, have superior marketing costs you already have the customer; superior credit costs you control the account, fundamentally the fraud costs are much lower; superior operating costs you are not building a new back-office system; vastly superior cost of equity, vastly superior cost of debt. So there is nothing about the product that isn't cheaper than the alternatives, overdraft and traditional payday."

Those two products have had too much influence on how banks determine what to charge for their deposit advances, Date adds: "Is this therefore a product that's expensive because it has to be, like traditional payday? Traditional payday I don't think can get much cheaper, because there's not enough margin in it. Or is it a product that is expensive because it can be? Because overdraft sets a price umbrella, and traditional payday sets a price umbrella," so banks say, " 'Whatever, just a little bit lower than that.' But that doesn't mean that pricing won't come in if there's competition."

He points to how prepaid cards were once much more expensive until Wal-Mart (WMT) drastically lowered the prices on its version. "I would like to think that the same dynamic is possible in small-dollar credit. I would love it if that were the case. I don't know that it is, but it's definitely worth doing the work."