WASHINGTON – A long-awaited final rule published this week that requires banks to keep better track of the owners of companies with accounts at their institutions is too little, too late in combatting money laundering and terrorism financing, according to financial crime specialists.

It is "shockingly soft," said Ross Delston, a Washington-based attorney and anti-money-laundering expert. "We should be calling it the pillow-top regulation."

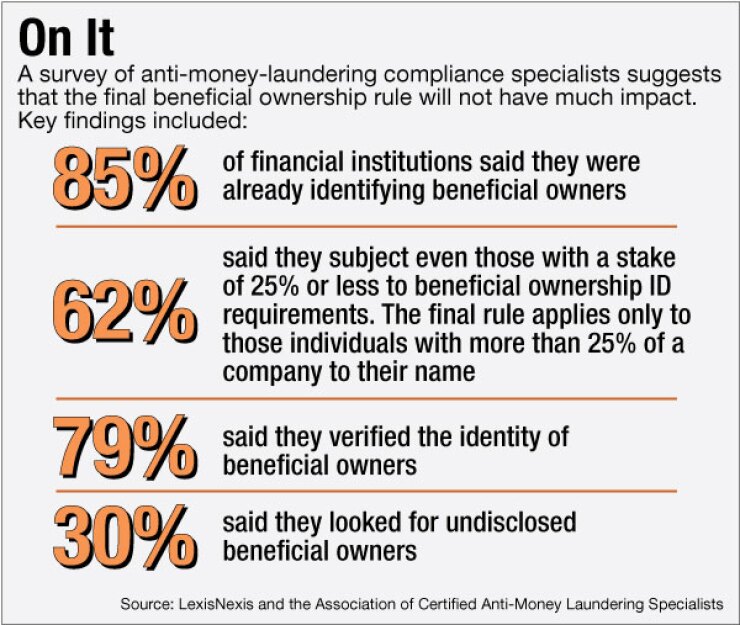

The rule will require banks to collect information on certain key individuals associated with a company. Financial institutions will have to ask for the names of a company's owners with a stake higher than 25%, and for individuals with "with significant managerial control" over the operations of the firm.

-

Along with publishing the long-awaited beneficial ownership rule, the Treasury and Justice Departments urged Congress to pass legislation to put the U.S. on par with foreign partners in the fight to curb the flow of illicit funds.

May 5 -

Sens. Sherrod Brown, D-Ohio, and Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., sent a letter to the Treasury Department on Thursday urging an investigation into whether any U.S. or U.S.-linked entities are associated with the Panama-based law firm Mossack Fonseca & Co. and its schemes to help wealthy individuals and businesses evade taxes and launder money.

April 7 -

Witnesses testifying on Capitol Hill said legislation requiring incorporating companies to state true owner information would combat launderers.

June 24

In certain cases – where no one owns more than 25% of a firm's assets – this could mean that the only person registered would be an executive, board member or some vaguely defined individual with similar functions.

Security advocates are worried this could allow bad actors to hide behind a shell company or a disconnected executive.

"The chairman of the board might have some high-level, 30,000-feet control of the bank – but they're not looking at the day-to-day operations," said Eric Lorber, a senior associate at the Financial Integrity Network. "Often, that's where money laundering occurs, where terrorism financing occurs."

Furthermore, experts say the rule only requires banks to perform rudimentary identity checks – to verify if each name offered by the company points to a real person, but not if the firm is being truthful.

"I have a memo to the U.S. Treasury: not everyone is honest," said Delston, noting that the rule allows banks to accept photocopies of identifying documents as proof, without even keeping them on file. "Photocopies can be very revealing if there is a fraudulent ID."

Part of the reason the rule isn't more onerous is due to a desire on the part of the Treasury Department's Financial Crimes Enforcement Network to limit the regulatory burden on financial institutions.

"The rule includes a very thorough regulatory impact assessment, and the costs and benefits were weighed," a Fincen spokesman said.

The final rule will also give banks two years to comply, instead of one year as was previously proposed.

The administration paired the rule with suggested new legislation that would require all newly formed companies to register with the Internal Revenue Service, along with other initiatives and bills from both Treasury and the Justice Department.

"Only Congress can fully close the loopholes that wealthy individuals and powerful corporations all too often take advantage of," President Barack Obama said Friday.

But critics argue that the administration was passing the buck on effective anti-money-laundering efforts to lawmakers, while reaping the political benefits of responding to the Panama Papers revelations.

The administration announced the initiatives on Thursday, just a few days before the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists released a database of thousands of entities potentially implicated in the use of offshore companies for tax evasion and money laundering.

"There's a lot of political momentum for transparency, but a lot of that political momentum is coming out of the Panama Papers," Lorber said.

But the administration's legislative proposals are "going to be a harder political push, because there's less of a momentum now that the [customer due diligence] rule has been passed," Lorber said.

Even if passed, a bill to create a central registry would only be of use to law enforcement; it would not be made public to allow financial institutions to cross-check that data with information provided by new client companies.

"The banks are saying, 'Well, that doesn't help us at all,' " said Alma Angotti, an anti-money-laundering adviser at Navigant.

Making the registry public could have irritated certain states – such as Delaware or Nevada – that are attached to their lax corporate formation rules, Angotti suggested.

"It looks like it might be a compromise between the states and the federal authorities," she said.

Because the bill would only apply to domestic firms, it would be easy for foreign companies to circumvent ownership identification requirements, said Carlos Garcia Pavia, LexisNexis Risk Solution's director of market planning.

"We have to consider that our financial institutions are doing business not only with U.S. companies but also with foreign companies," he said.

The beneficial ownership rule also does not impose additional reporting requirements on trusts or on investment advisors, who manage assets for huge market players, including hedge funds, mutual funds and private equity funds. That is another serious flaw, some argued.

"The amount of money that goes into these institutions is trillions of dollars, but they're not closely regulated," Lorber said.

Treasury has shied away from asking these individuals to comply with the same type of requirements than banks because that would be a hard sell, he added.

"It's hard to tell the investment advisors to make sure that all the funds they are dealing with are clean, because it's a gargantuan task," Lorber said.

Additionally, the rule included a grandfathering clause, allowing companies that have already opened bank accounts to forgo the beneficial ownership requirements.

"There could be accounts that have been held for a period of time by individuals for the purpose of tax evasion or money laundering activity that might not have been picked up," Lorber said.

This could create a market for shell companies, Delston said. "There will be trafficking in existing company accounts, because there won't be any information [on banks' books] about them."