Lenders are questioning the legal justification for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau's proposing a 36% annual percentage rate threshold as part of its plan to rein in payday lending, claiming loans made at that rate are unprofitable.

The centerpiece of the CFPB's

"Fundamentally, what the bureau is saying is they think a loan with an all-in interest rate above 36% is a potentially dangerous or risky loan to consumers," said Leonard Chanin, of counsel at Morrison & Foerster, who represents installment lenders.

-

We need a variety of small-dollar credit products to meet a variety of consumer needs. So the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau's proposed payday plan must provide more flexibility.

June 7 -

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau's complex payday lending proposal is sparking concerns that state legislatures will try to repeal existing usury laws and allow a parade of pro-payday-lending bills to move forward.

June 2 -

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau's long-awaited proposal to establish the first federal rules for payday, auto title and high-cost installment loans did not include a provision that banks had planned would allow them to compete by offering small-dollar installment loans.

June 2 -

While existing state laws show that payday lending curbs lead to positive outcomes, those laws will still benefit from a strong Consumer Financial Protection Bureau rule.

June 1 -

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau will unveil sweeping federal regulations Thursday for payday lenders that could open the door for competition from banks, while forcing lenders to move toward longer-term installment loans. Here's what to track when the plan is released.

May 31 -

The new regulations are meant to close loopholes in an interest rate cap that applies to active-duty soldiers and sailors. But financial institutions won at least one important concession.

July 21

The 36% figure has been the subject of intense

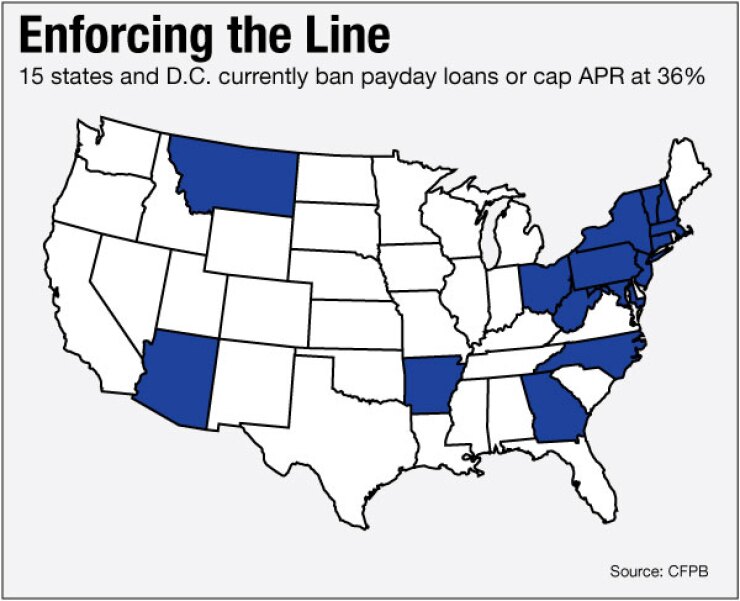

The agency is following the precedent set by the Military Lending Act of 2006, which capped payday loans to military personnel at a 36% annual percentage rate. The bureau said in its proposal that numerous state laws impose a 36% APR usury limit, making it illegal to charge more.

Consumer advocates credit the 36% APR cutoff to various states' adoption of the Uniform Small Loan Law from 1914 to 1943, and to the Russell Sage Foundation, a progressive research group.

"From a broad policy standpoint, looking at the economics of lending, there is a trade-off between interest rates and costs to have a profitable model," said Mike Calhoun, president of the Center for Responsible Lending, who cited the "congressional recognized standard" of 36% in the Military Lending Act. "High interest rates means a large percentage of your loans are unaffordable."

Bankers opposed the 36% figure when it was debated for military personnel a decade ago, fearing that it would eventually apply to consumers more broadly. The CFPB's proposal would effectively do just that.

Lenders are also taking issue with the 36% rate because the CFPB is prohibited by the Dodd-Frank Act from setting interest rates. The bureau has gone around that restriction by proposing lenders make a reasonable assessment of a borrowers' ability to repay certain loans above the 36% line, citing evidence that it causes consumer harm. As a result, the 36% figure is not a hard cap.

Setting an annual percentage rate could help borrowers comparison shop, though some lenders think it is confusing for consumers and inappropriate for small-dollar loans. A borrower looking for a $300, two-week loan typically wants to know what the loan will cost, and may compare a payday loan against the alternative of a bank overdraft fee that costs $35, which can have a higher APR.

Jeremy Rosenblum, a practice leader in the financial services group at Ballard Spahr, said he thinks the 36% number is likely to form the basis for a lawsuit challenging a final payday rule.

"Congress has explicitly told the CFPB to stay away from any usury limit, yet this is a usury limit and it is beyond their authority," Rosenblum said. "When they are trying to put a high percentage of the industry out of business, they can expect a legal challenge."

"At some point, they are not prohibiting it, but they are making it so difficult that it's tantamount to a prohibition," Rosenblum added.

For now, companies are focusing their attention on comment letters due by Sept. 14, since they can file a lawsuit only after a final rule is released.

The CFPB views payday loans as high-cost, predatory products that are marketed as a source of short-term, emergency credit, but actually ensnare consumers in long-term debt.

The agency estimates that there will be a 60% to 70% reduction in payday loan volume as a result of the plan. Still, the bureau expects only a 7% to 11% reduction in overall payday loan borrowers under the proposal, as it seeks to eliminate the ability of lenders to allow borrowers to take out multiple loans, which make up a large share of payday loans being originated.

Additionally, lenders are worried because the CFPB changes how the APR is defined in its plan. It would include finance charges and other fees incurred to extend credit.

As a result, the proposal would create a new interest rate standard that includes ancillary products, application fees and credit insurance, which currently are excluded from APR calculations under Regulation Z, which implements the Truth-in-Lending Act.

An industry was alarmed at that idea.

"What is the bureau's justification for creating a totally new yardstick?" asked Don Lampe, a partner at Morrison & Foerster. "They are now saying Regulation Z is not protective enough of consumers and they are putting back into the APR what Reg Z and Truth in Lending excluded for many years. The justification is that these consumer protections ought to be triggered based the CFPB's own assessment of abusiveness and unfairness, not under Regulation Z standards."