Want unlimited access to top ideas and insights?

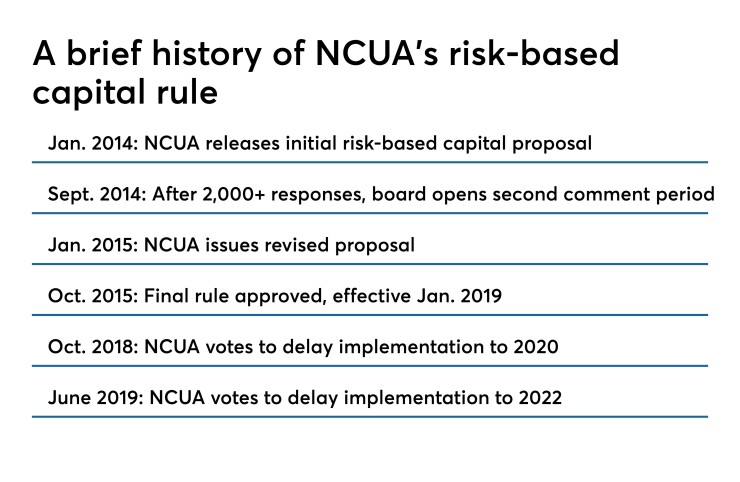

In a split vote along party lines, the National Credit Union Administration proposed Thursday a further delay to implementation of a contentious risk-based capital rule, pushing off compliance for two years until 2022.

If approved, it would be the second such delay for the rule, which would generally increase capital requirements for larger credit unions, after the agency voted last year to push the

The NCUA said it would tackle three issues prior to the rule going into effect — a separate plan to expand the use of subordinated debt by credit unions, new regulations on asset securitization and the possibility of creating a credit union equivalent of the Community Bank Leverage Ratio.

NCUA Chairman Rodney Hood said two additional years allows for a "surgical approach," giving the agency enough time to propose and finalize changes in order to conduct a well-integrated implementation.

The delay means that if the risk-based capital rule takes effect in 2022, the saga will have stretched out for roughly a decade. The agency first began discussing changes to risk-based capital requirements in 2012. (It did not issue a proposal until 2014.)

“Do we really need a full decade to holistically and comprehensively evaluate capital standards?” asked Todd Harper, an NCUA board member.

That timeline was a major sticking point for Harper, the board’s only Democrat and the lone dissenting voice in Thursday’s vote. In his remarks and an extensive question-and-answer session with Larry Fazio, director of the agency’s Office of Examinations and Insurance, Harper noted that the current risk-based capital standard only applies to credit unions with more than $500 million in assets, or about 10% of all federally insured credit unions.

Harper said that rather than finding new ways to modify and delay risk-based capital rules, the board would be better off focusing on issues that have an impact on a wider swath of credit unions.

“The agency’s supervisory efforts should focus on institutions and activities that pose the greatest risk" to the National Credit Union Share Insurance Fund, such as concentration risk, Harper said, noting that

The failures of

Any further delay in addressing those issues, Harper said, “will produce consequences for the entire credit union system.”

Sub debt and other proposals

During the meeting, Hood pledged that the board would take up a proposal on subordinated debt by the end of 2019. The agency is considering changing how subordinated debt is used by credit unions, potentially expanding it beyond just institutions with a low-income designation, which are permitted to skirt certain rules while others without that designation are not.

Harper questioned Fazio on how many credit unions would be likely to utilize expanded powers. Fazio said some credit unions likely would, but acknowledged it would probably not be many.

While Harper said he would be willing to work with the board on separate regulations related to capital issues, he argued that delaying the overall risk-based capital rule further could pose additional risks to the share insurance fund and slow down the agency’s compliance with recent recommendations from the Government Accountability Office and the NCUA’s own Office of the Inspector General.

Hood also suggested a credit union version of the Community Bank Leverage Ratio might make sense. Under a regulatory relief law adopted by Congress last year, banks with less than $10 billion of assets are allowed to opt for a simple capital ratio rather than complying with multiple risk-based measures.

Hood said the equivalent for credit unions could be “a simple, effective way to provide relief if credit unions maintain strong capital levels.”

But Mark McWatters, the third NCUA board member, suggested such a plan could effectively be a way for credit unions to avoid dealing with the new risk-based capital rule.

“We’d be applying a rule and saying ‘You must have this kind of capital,’ and then coming along a year later and saying ‘Here’s another way to get it,'" he said.

If credit unions elect to use the Community Bank Leverage Ratio instead of the risk-based capital rule, he said, “they don’t have to go through the brain damage of risk-based capital.”

‘It defies simple logic’

Unsurprisingly, bankers were incredulous that the NCUA would kick the can further down the road when banks have already been complying with their own risk-based capital requirements for five years, without a threshold exempting certain institutions.

“It defies simple logic that the NCUA would propose again to delay imposing comparable rules for the nation’s credit unions, when the agency is simultaneously allowing and encouraging credit unions to operate exactly like banks,” Rob Nichols, president and CEO of the American Bankers Association, said by email. Further delay, he added, “is even more troubling when you consider that these rules could have helped prevent the nearly $1 billion in losses to the credit union insurance fund stemming from the failure of credit unions involved in New York’s much-publicized taxi medallion lending scandal.”

As for the NCUA looking at the Community Bank Leverage Ratio, Chris Cole, senior regulatory counsel for the Independent Community Bankers of America, noted credit unions already have a net worth-to-asset requirement that is close to the leverage ratio. "What more would it measure for credit unions than the net worth does right now?" he said.

The ICBA believes the 7% figure that is used to signify a well-capitalized credit union is too low. Banking regulators are contemplating a 9% CBLR for banks, he said, adding that the group also opposes supplemental capital for credit unions.

Credit union groups, however, were generally upbeat about the delay, although Dan Berger, CEO of the National Association of Federally-Insured Credit Unions, said he continues to have concerns about the underlying rule. "NAFCU remains concerned about the regulatory burdens and costs the rule will place on credit unions,” Berger said in a statement. NAFCU “will continue to encourage the agency to design a true risk-based capital system for credit union."

While only a limited amount of Thursday’s board meeting was dedicated to subordinated debt, the National Association of State Credit Union Supervisors praised the agency for wrapping that issue in with the risk-based capital rule.

“We have long held that subordinated debt should be a part of the risk-based capital framework because it encourages well-managed credit unions to attract additional loss-absorbing forms of capital that they would otherwise forego,” Lucy Ito, the supervisor association's president and CEO, said in a statement. “Indeed, the point of risk-based capital rulemaking is to increase the capital buffer standing before the share insurance fund and subordinated debt is wholly consistent with that goal.”

Keith Leggett, a retired ABA economist who blogs frequently about credit union issues, said bankers are also likely to oppose any subordinated debt rule the NCUA proposes, even if it applies only to the handful of credit unions that would need to raise extra capital if a risk-based capital standard is implemented.

"It's the proverbial camel's nose under the tent," Leggett said. "The agency would be able to point to it as a successful experiment and push for the expansion of secondary capital" as part of the primary capital ratio.

Dennis Dollar, a former NCUA chairman and credit union consultant, called the RBC delay “a sign of the swinging regulatory pendulum” and an indication that the current board make-up doesn’t feel beholden to policies proposed during former Chairman Debbie Matz’s tenure.

“Boards change, as do chairmen and priorities,” said Dollar, noting that circumstances in the industry and the market place are vastly different than when the rule first went up for debate.

“It is very possible that the time for RBC, as it was proposed ten years ago, has passed and will be replaced with a more modernized and flexible capital regime that incorporates supplemental capital and has a risk-weighting system that is more credit union by credit union and less one-size-fits-all,” he added.

Harper was the only “no” vote on the panel Thursday, but McWatters does not appear to be a lock. When he first joined the board in 2015, he was a dissenting voice against the risk-based capital rule, and he said Thursday he remains concerned that the rule will ultimately violate the Federal Credit Union Act.

Ken McCarthy contributed to this report.

This story was updated at 3:47 P.M. on June 21, 2019.