Score one for the payments industry.

In the never-ending fight over who should bear the cost of processing credit and debit card transactions, retailers seemed to gain the upper hand last month when Congress decided against trying to remove caps on swipe fees. But U.S. banks and payments firms earned a win of their own last week when the Department of Justice opted to drop its appeal of a closely watched case centering on whether merchants should be allowed to encourage the use of particular cards.

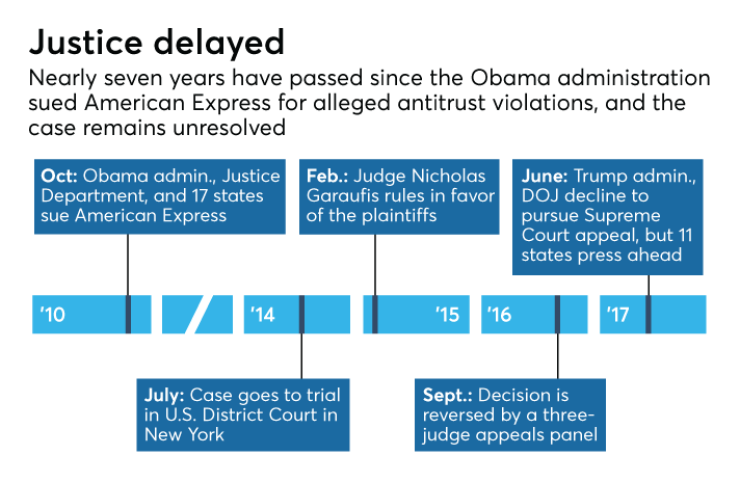

The Department of Justice has been locked for seven years in a legal battle with American Express over contractual provisions barring merchants that accept Amex cards from promoting lower-cost cards offered by the firm’s competitors. But on Friday, the Justice Department essentially conceded defeat, saying that it will not ask the Supreme Court to review an appeals court ruling in favor of American Express.

The decision to abandon a major antitrust case is an example of Trump administration officials undermining the efforts of their predecessors in the Obama administration.

It may also signal that the new administration intends to deprioritize antitrust enforcement. The Amex case will set a precedent regarding the restrictions that the card networks can place on merchants, who chafe at the high cost of accepting card payments.

“Certainly it’s good news for the industry,” said Eric Grover, a payments consultant.

The Trump administration’s decision is not the final word in

But the Supreme Court is generally much more likely to hear lawsuits when the Justice Department asks for a review. The court is expected to decide later this year whether it will take the Amex case.

“We believe the DOJ’s decision not to proceed sends a strong signal that this seven-year litigation should come to an end,” American Express said in a written statement.

The New York-based company stated in a recent regulatory filing that if retailers were to engage in significantly more steering to lower-cost cards, it could have a material adverse impact on the company’s business.

In the broader fight over swipe fees,

The antitrust case hinges on whether, in assessing the impact of Amex’s rules on competition, the courts should consider only the impact on merchants, or whether the impact on consumers should also be taken into account.

In 2015, a U.S. District Court judge ruled against American Express, finding that the company’s rules barring merchants from steering consumers to particular cards had enabled Amex, Visa, Mastercard and Discover Financial Services to raise their swipe fees more easily and profitably than would have been possible otherwise.

Those fees, which add up to tens of billions of dollars each year, are typically split between the card network and the bank that issues the card.

But last year,

The 11 states, led by Ohio, argued in their recent petition to the Supreme Court that the appeals court’s analysis was faulty. “It is often the case that pricing in one market affects pricing in another, but that interdependency has never collapsed the two markets into one for antitrust purposes,” the states wrote.

Retail giants including Home Depot, Amazon and 7-Eleven maintain that Amex’s ban on steering customers to particular cards has harmed their businesses.

“Shoppers will perceive no difference in selecting one payment card versus another, and will be motivated to choose the card offering the higher rewards,” the merchants wrote last year in a legal brief.

Meanwhile, American Express casts itself as an underdog that uses comparatively high fees to compete against Visa and Mastercard.

“Many firms, including Amex, can only compete with their larger rivals by investing continuously to offer a superior product to win the loyalty of their customers,” the company wrote in a 2015 court filing.

In another recent case involving swipe fees, the Supreme Court handed the merchants a victory. The court’s 8-0 decision in March overturned an appeals court ruling that upheld a New York law barring retailers from charging customers more for paying with credit cards, which typically carry higher swipe fees than debit cards.

But that case hinged on whether the New York law infringed on the merchants’ free speech rights — a separate legal issue from the ones raised in the Amex case.

“This would be something new for the court,” said Lawrence White, a professor at New York University’s Stern School of Business, referring to the lack of Supreme Court precedent regarding the antitrust issues raised by the American Express case.

“Maybe that’s an argument for why the court ought to take it up. Or it could be an argument for why the court says we need to see more analysis down at the circuit court level.”