-

Executives at Lead Bank in Garden City, Mo., are hopeful that offering small businesses more high-touch services, such as consulting, will provide an advantage in an area that has become fiercely competitive.

January 22 -

Leading indicators are still so-so, but normally bearish U.S. Bancorp CEO Richard Davis predicts more loan demand in the second half based on his conversations with customers, who he says want to "get things moving."

January 22 -

The Securities and Exchange Commission has fined Fifth Third Bancorp (FITB) for misclassifying troubled loans during the housing crisis.

December 4 -

Community banks are reporting first-quarter declines in net interest income despite increased lending. Low rates and competition are to blame.

April 25

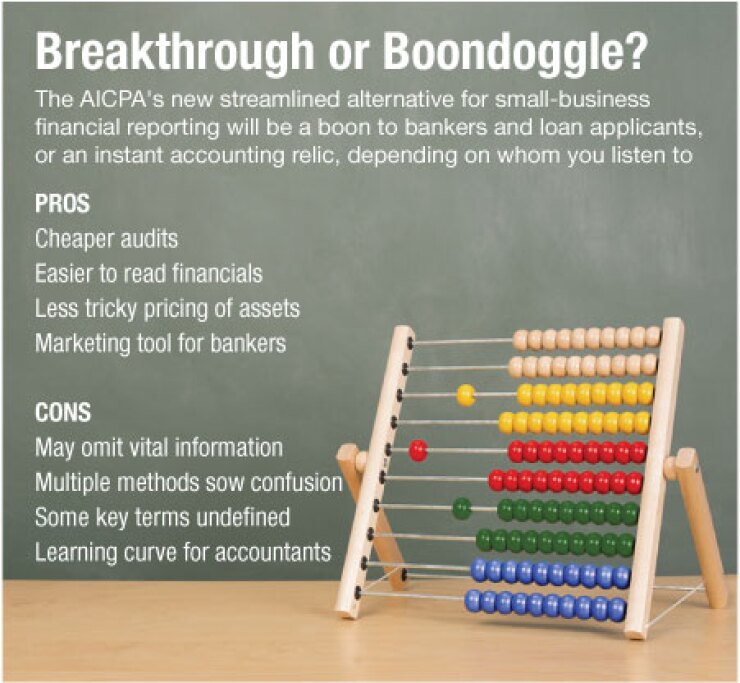

Nobody wants accounting to get any more arcane, least of all commercial lenders. Untangling a small business' financials is hard enough already.

A new effort to streamline financial reporting could help credit officers make small-business loans without studying a mountain of footnote-laden documents. The Financial Reporting Framework for Small and Medium-Sized Entities is touted as a simpler method to assess the health of private companies, which could have the added benefit of stimulating lending.

But as always in accounting, there are complications. The new framework has exposed decades-old divisions between accounting groups, roiling a field unaccustomed to emotional debate.

Advocates of the new framework say it could help bankers land more small-business clients, who would spend less money to prepare accurate financials that are central to credit reviews. Critics say it will just cause new accounting headaches, by introducing a shaky set of guidelines that differ from generally accepted accounting principles, or GAAP.

"Of course a banker would like to have audited financial statements, and this may make it cheaper to get them," said Mike Gullette, the American Bankers Association's vice president of accounting and financial management. "But bankers now are going to have two different frameworks to think about, and it could take years to determine if a banker will prefer one over the next."

The

The framework isn't a replacement for GAAP, says Dan Noll, the AICPA's director of accounting standards. It's meant for traditional owner-managed companies that don't want to use GAAP but find that other accounting standards "aren't quite cutting the mustard," he says.

"This framework follows very traditional accounting principles that help put together a picture of what a company's assets and liabilities are," Noll says. "On that basis, bankers would be getting a pretty clear picture of a borrower."

For many small businesses that have used it, the simplified reporting framework is welcome.

"If you excuse the expression of passion around an accounting product, I'd say we were extremely happy that the AICPA put this forward and that the banks would work with us," said Keith Willy, a partner at Twain Financial Partners in St. Louis, a small firm founded last year that manages assets for banks.

Willy persuaded the company's backers to accept financials prepared under the new framework last year, a move that saved around $200,000 in accounting and other costs. The new guidelines don't require the company to consolidate its equity holdings on its balance sheet, a labor-intensive process that only serves to "clutter up your financial statement at the expense of transparency," Willy said.

The framework is not an authoritative set of rules, and banks are free to choose whether to accept financial statements prepared in accordance with it or to stick with GAAP.

But banks that do use it could get a leg up in small-business lending by making it easier and less expensive for companies to apply for loans, advocates say.

Enterprise Financial Services (EFSC) in St. Louis is one of the early adopters. The $3.2 billion-asset company thinks that the framework can help it land small-business customers who are reluctant to undergo a full audit, according to Theresa Bible, Enterprise's senior vice president of credit.

"We look at it as a competitive advantage. If we can provide an alternative to an audit and a tax return, we would have an advantage versus a company that would want a small-business owner to do a full audit," Bible said.

Enterprise has begun educating the accounting firms it works with about the framework, and may hold educational sessions for potential clients sessions that could double as marketing opportunities, Bible says.

Though it is not yet widely used, the framework "is starting to gain some traction" among companies Enterprise Financial works with, Bible says. A

Inevitable Fight

In the accounting community, the release of the new framework rekindled an old debate about the complexity of accounting standards, and whether some rules should be relaxed to accommodate smaller, private companies.

"This controversy has been brewing since Sarbanes-Oxley how do you address private accounting and auditing?" said Gullette. "There is a perception that because accounting has become too complex, it is getting too expensive to ask for an audit of financial statements."

The ABA has taken no official stance on the new framework, Gullette notes.

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act, a response to the enormous accounting scandals that broke in the early 2000s, increased auditors' liability for faulty financial statements. This change made it much more expensive for companies to have their financials audited, which can be a serious problem for small companies, Gullette said.

In response, groups that oversee accounting guidelines have discussed ways to ease this burden. The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), which oversees changes to GAAP, has been working for the past several years to develop a less rigorous GAAP alternative so-called Little GAAP for small private companies, but has not yet unveiled the new rules.

The AICPA's new framework is a separate effort apparently aimed at a similar goal. This has rankled many accountants, who see rivalry and not good policy as the motivation for the competing efforts. Sarbanes-Oxley established the FASB as the de facto referee of accounting rules, greatly reducing the power and responsibility of the AICPA, Gullette said.

Several of the

The National Association of State Boards of Accountancy (NASBA), a group of state licensing agencies, denounced the framework shortly after it was issued, saying that it would "significantly weaken the financial reporting of private companies" and would be hard to regulate and enforce. However, the NASBA later switched its position and said it would cooperate with the AICPA.

The debate was

One notable intervention in the debate came from former Securities and Exchange Commission Chief Accountant Walter Schuetze, who called the framework a "sack of mush" in a

Clearer or Murkier?

However this debate ends up, bankers would do well to educate themselves on the framework, since they are likely to encounter it in dealing with small-business borrowers, Gullette says.

The financial reporting framework can be considered a hybrid between a tax return and a GAAP statement. It uses the accrual basis of accounting, which is often used in tax accounting, while incorporating the disclosures required under GAAP.

Perhaps the most significant and potentially money-saving feature of the new framework is that it steers away from fair-value accounting, which is required under GAAP and can be complicated and expensive to prepare. It allows companies to report costs when they are incurred and revenue when it is earned, rather than continuously repricing assets.

The framework also simplifies the presentation of complex assets, permitting companies to disclose derivatives transactions and leases rather than calculate their impact on their balance sheets. This simplification could reduce the need for companies to hire experts to appraise contracts and complex financial instruments.

It should be easier to keep current with the framework than with the GAAP standards, which are usually updated several times a year. The AICPA plans to update the framework every three or four years, after an initial tweak to address issues that arise during the rollout.

While the new framework is certainly streamlined it is about 250 pages, thousands less than the full set of GAAP rules it could give a muddier picture of a borrower's finances than GAAP. Analysts at the consulting and accounting firm Grant Thornton concluded that it was too soon to say whether the framework's simplicity

But proper underwriting depends more on a loan officer's diligence than the accounting framework a company uses, Gullette said.

"Small-business lending is all about how well the banker understands the business. And if the banker doesn't understand the business, I don't know why he would lend money anyway," he said.