-

Sovereign Bank will change its name to Santander Bank and spend $200 million to upgrade branches and roll out an advertising campaign.

July 31 -

Santander Bank, formerly Sovereign Bank, has launched a rewards-heavy credit card and made other creative retail moves in the U.S. as it tries to establish an identity beyond that of the foreign-owned bank with the tricky name.

February 5 -

Santander is poised to make its long-awaited name change at Sovereign Bank in Boston, capping years of work on its U.S. unit that included a financial overhaul, systems integration and charter switch.

August 26

If any bank is in need of a fresh start in the U.S. in 2015 it's Santander Bank.

Over the past year, the U.S. unit of Spanish banking giant Banco Santander failed its federal stress test and faced charges of redlining; the lending policies of its affiliated subprime automobile lender came under scrutiny from both the Justice Department and New York banking regulators; and its holding company got into hot water with the Federal Reserve Board for paying a dividend to shareholders without first receiving the Fed's approval.

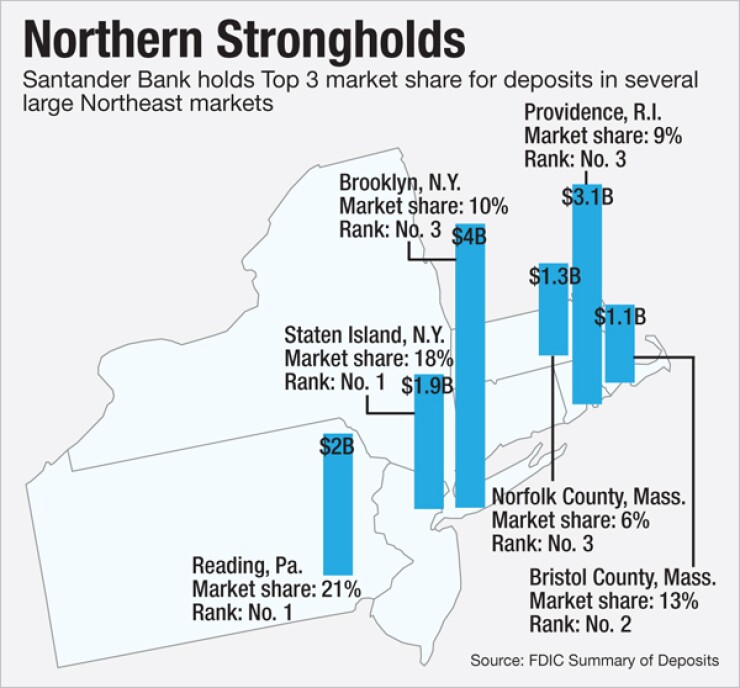

On top of all that, the $77 billion-asset bank continued to lose deposit share in some of its key markets in the Northeast. Providence, New York, Philadelphia and Reading, Pa. where it competes with a small bank run by the ex-CEO of Santander's predecessor are all markets where Santander has ceded significant share to both larger and smaller competitors.

Banco Santander officials acknowledge that 2014 was a rough year and say they are committed to reversing its U.S. bank's fortunes in 2015.

"In the U.S. ... we have two focuses," Jose Antonio Alvarez, Banco Santander's chief executive officer, said during a Nov. 4 conference call, when he was still the company's chief financial officer. "One is building the commercial franchise and the second one is to continue to invest in the regulatory developments, in order to comply with the expectations of the regulators." (Alvarez took over as CEO on Jan. 1.)

Santander is an active commercial real estate lender and has a growing presence in credit cards and observers expect the bank to double down in those areas. And despite the heightened scrutiny of subprime auto lenders, some observers believe Santander is well-positioned to gain share in the auto-financing market.

Still, some analysts and competitors wonder if Santander has lost its competitive edge.

"When I talk to banks and mention Santander, they look at me with a blank stare," said Matthew Schultheis, an analyst at Boenning & Scattergood who covers banks in Santander's markets. "It's almost like they're a non-entity."

"I rarely hear about banks losing big commercial real estate or [commercial-and-industrial] loans to Santander," added Matthew Kelley, an analyst at Sterne Agee who follows banks that compete against Santander, including $35 billion-asset People's United Financial in Bridgeport, Conn., and $22 billion-asset Webster Financial in Waterbury, Conn.

"Small and mid-sized institutions have been the beneficiaries of picking up customers, loans and staff from Santander," Kelley said.

Santander's rocky 2014 began in March, when the bank

Meanwhile, Santander Consumer USA Holdings, which held an initial public offering in January 2014 but is still majority-owned by Banco Santander, received inquiries from regulators about its

Santander's mortgage lending also came under the microscope.

Santander even had a supporting role in the secret recordings of conversations between the New York Fed and Goldman Sachs, which raised questions about whether the Fed is too close to the banks it regulates. In one of the taped conversations, a regulator described a deal between Santander and Goldman Sachs as

To conclude the year, Emilio Botín, the longtime chairman of Banco Santander, passed away at age 79. Botín had led Banco Santander since 1986, growing the company from a sleepy regional lender to a global bank. Botín's daughter, Ana, was

The bank, formerly headquartered in Pennsylvania but now based in Boston, also has a new U.S. chairman. Highlighting its focus on strengthening its relationship with regulators, the bank in December

Santander officials did not respond to interview requests so it's unclear how the board and management aim to boost the bank's stature in the Northeast.

In the meantime, competitors are stealing its customers.

Ralph Branca, president and chief executive at $307 million-asset Victory State Bank in Staten Island, N.Y., said his institution derives between 20% and 25% of its new business directly from former Santander clients.

"What hurts them is that they don't deliver the same type of personal service that a community bank does," Branca said. "They outsource all their decisions."

Santander is the largest bank on Staten Island, with about 18% of the market at June 30, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.'s Summary of Deposits. However, Santander's market share in Staten Island has declined sharply over the past five years, falling from 24.30% in mid-2009.

It's also losing share in Reading, Pa., a market where it's held the top ranking since 1998, according to the FDIC.

That's where it competes head-to-head with the $6.5 billion-asset Customers Bank, an upstart run by Jay Sidhu, the longtime chief executive of Santander's predecessor, Sovereign Bank. Sidhu built Sovereign Bank into an $89 billion-asset company before selling a large chunk of it to Santander. (He was

Market-share numbers show that Customers has zoomed up the rankings, largely at the expense of Santander Bank. Sidhu could not be reached for comment.

In metropolitan Reading, Customers Bank has climbed from the No. 12 position in market share in 2011, with about 2% of the market, to No. 2 at June 30, with 17% of the market. Customers Bank's deposits in Reading during that time have risen more than 1,000% to $1.6 billion. Meanwhile, Santander has maintained its No. 1 position, but its market share during the same period has fallen from 30.96% to 20.65%.

Schultheis cautioned that FDIC market share numbers can be skewed if a bank parks corporate deposits in a specific market.

Observers note that Santander has several areas of strength, namely in commercial real estate lending and

"They've got an aggressive real-estate operation in Boston," said Stan Ragalevsky, a banking attorney at K&L Gates in Boston. "They've done it by hiring top-quality people and using them to go after the biggest and best deals. They also got ahead of the market while some other banks were in a bit of a lull."

Santander is also one of the largest multifamily lenders in the U.S. It held a balance of $9.2 billion in multifamily loans as of June 30, the fifth-largest portfolio among all U.S. lenders, according to SNL Financial. That was also a 24% increase in multifamily loans from a year earlier. At the same time, Santander has become less reliant on multifamily loans, as its concentration in the category fell 268 basis points, to 12.17%, at June 30, from a year earlier.

Santander's auto-lending business also shows great promise, several analysts have said. Because it has "easy access to capital" from its large parent company, and also because it has more channels for new business than other lenders, including an

On the expense side, Santander is grappling with the same dilemma as many other U.S. banks what should it do about its retail branches. A recent study conducted by Sanford C. Bernstein analyst Kevin St. Pierre suggested Santander should get busy closing branches to cut costs. Santander could close 288 branches, or about 41% of its network, based on individual branch profitability and location close to other branches, St. Pierre wrote in the report. (St. Pierre's report did not just single out Santander. He recommended sweeping branch closures for about four-dozen institutions.)

Others, though, say that Santander's chief focus should be on competing for loan business.

"I never hear people say, 'We lost a bunch of loans to Santander,'" Schultheis said.