-

The federal agencies treat PE players as "slippery" characters, impose "draconian" limits on them and make the troubled European economy more appealing for bank deals, investor Ross says.

May 22 -

The community banking sector is starving for capital, and yet debate is dominated by complaints about regulatory burden. Instead, banks need to push regulators to let private equity investors assist small institutions.

December 14

Advocates of private equity's ability to clean up banking should look at North Carolina to make their case.

Since 2010 private equity firms have pumped more than $500 million into a handful of banking companies, turning once-marginal banks into consolidators and scooping up failures and laggards from the mountains to the coast.

Average North Carolinians hardly notice because private equity prefers to stay behind the scenes. But big changes would have been obvious had these large investors stayed on the sidelines, industry observers say.

Without private equity "we would have had a number of weaker banks that most likely wouldn't be lending, which would have hurt commerce," says Lee Burrows, the chief executive of Banks Street Partners, an Atlanta firm that has advised on recent acquisitions in the state. "PE has restored the health of a number of community banks in the state, keeping them in business to lend money."

Regulators have worried that private equity would

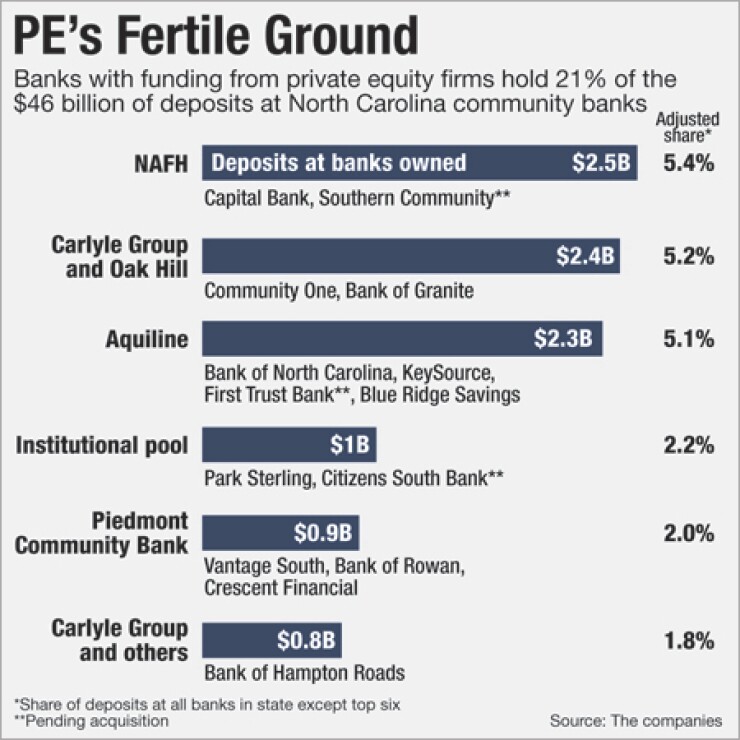

Yet private equity has gained a solid toehold across North Carolina in short order. Excluding North Carolina's six biggest banks, financial institutions with private equity backing now control more than a fifth of its deposits. Though private equity does not deserve full credit for reviving the state's economy, it justifiably can claim a supporting role.

Unemployment in the state fell to 9.4% in April, compared with nearly 11% in June 2010, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. And the banking system is slowly improving. The median ratio of delinquent loans to total loans at North Carolina banks fell to 4.88% in the first quarter, compared with nearly 5.5% in 2010, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. The median pretax return on assets reached 0.53% in the first quarter, compared with 0.06% in 2010.

"Private equity is absolutely a plus," says Cecil Sewell, a veteran North Carolina banker who was the chief executive of Centura Banks when it

Private equity is involved across the state. BNC Bancorp (BNCN) in High Point, armed with funding from Aquiline Capital Partners, has bought three failed banks in the Carolinas along with several other acquisitions. Last week alone, the company

North American Financial Holdings bought Capital Bank (CBKN) in Raleigh, and

"There are a couple of banks that received capital to be consolidators," says Jeff Adams, a managing director at Carson Medlin, a division of Monroe Securities. "Without [that capital] they would be been focused internally and righting their own ships."

Banks backed by private equity are also looking at targets beyond North Carolina. BNC has bought failed banks on the South Carolina coast, while North American Financial has sizable stakes in banks in Tennessee and Florida.

"There is tremendous opportunity for these names to soak up a lot of" banks in surrounding states, Adams says. "The capital is all aggregated in North Carolina, and the people involved with these new bank consolidators were from banks there were acquirers in the 1980s and 1990s. These guys are getting all the calls."

Private equity became a godsend after local investors largely turned their backs on community banks in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis.

"There was a day five years ago when the average investor was happy to invest in community banks," says Burrows, who is also a former chairman of Little Bank (LTLB) in Kinston, N.C. "But when the local investor disappeared someone had to step in. Local investors didn't have the appetite or financial fortitude to make those investments."

Private equity may be reshaping the banking system, but the changes have gone largely unnoticed in the state. Locals have grown accustomed to bank consolidation, which allowed NationsBank and First Union to build big franchises. So when M&A changes the signs at the local branch, few residents realize that out-of-town money is playing a leading role.

Often, the executives that appear at local events are familiar faces. W. Swope Montgomery remains the CEO at BNC Bancorp despite a big investment from Aquiline. Ken Thompson, the former CEO of First Union and Wachovia, is Aquiline's board representative at BNC, though he has kept a relatively low profile.

Scott Custer, a former CEO of RBC Centura Bank, is the public face for Piedmont Community Bank Holdings, which is backed by Stone Point Capital and Lightyear Capital. Park Sterling (PSTB), supported by a pool of institutional funds, recruited Bud Baker, a former Wachovia chairman and CEO, to play an active role in its growth.

"The customer-facing people and many of the senior managers are familiar," says Tony Plath, a finance professor at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. "Private equity has kept the flavor of community banking but what is under the hood has totally changed. To the average citizen the impact isn't discernible, but it has really been transformative."

The public will benefit further as private equity firms buy more banks and install a more-disciplined approach to lending, Plath says.

However, he and others acknowledge that some of the advantages of traditional community banking will disappear.

"The physics of banking have changed" with the addition of private equity, he says. "The detriment of PE is that we are removing local control of money from small town America. We are essentially creating little Bank of Americas. Local control of money and management decisions is gone."

Sewell, who at one point was set to serve as a director for an investment group set on buying banks, agrees. He asserts that PE-backed banks will take fewer chances in lending, particularly with start-up businesses. "Community banks for many years served as a type of venture capital" for start-ups and young businesses, he says.

"That's not the case anymore, and that is the way it should be," Sewell says. "Private equity is a tough taskmaster, but I think banking needs a tougher taskmaster. I think it will bring discipline to the industry, which is what it needs right now."

Private equity's exit strategy remains unclear, so it's too early for a final judgment of its performance. Until the equity markets settle down, it may prove difficult for the private equity firms to sell their banks or take their holdings public. Those moves could be years down the road, giving bankers in the state more time to watch, observe and learn.

"It is going to be interesting to watch it play out," Sewell says.